Running a half-marathon with ITB Pain

I never was and am not much of a runner. Despite having played soccer throughout adolescence I could never get motivated to do longer distance runs. However what I did enjoy was sprinting and I was quite good at that too.

But we all know that growth comes from the things that you do outside of your comfort zone. The things that challenge you to step outside of your routines that feel familiar and comfortable.

I never set any new year’s resolutions because I feel like you shouldn’t let a date dictate how or when you start to approach your goals, hence my life motto: “The first step to get the things you want in life is this – decide what you want.” But, when my running fanatic brother texted me in November 2021 if I wanted to run the Berlin Half Marathon in April ‘22, this posed as a good new year’s resolution AND even more so as the perfect opportunity for me to step outside of my comfort zone.

“The first step to get the things you want in life is this – decide what you want.”

At the time, my baseline training condition as far as running was concerned was pretty much 0. I was training in the gym 5 days a week and playing recreational tennis 1-2 times a week. I couldn’t even remember the last time I ran anything beyond 3km let alone scratching the 10k mark and I needed to run double that and then some. That meant I needed to get to work.

I got myself a training plan that seemed reasonable to me in terms of weekly training days, weekly mileage and week-by-week progressions and started to hit the road.

Making Newbie-Gains

Just like a novice lifter I made “newbie gains” quite quickly, which was intensely motivating and seeing the progress over the course of the first weeks kept my spirits up. My mileage went up, my average heart rate decreased, so did my resting heart rate and I could shave some seconds off my average pace per run. But I soon realized that I needed to do something about my gym routine as the compounded training load and volume of my runs in combination with lifting 5 days a week and playing tennis twice a week was becoming too much. If I am dead set on a goal I am quite strict on doing what’s necessary to achieve it and running had become my top priority. So my lifts had taken a back seat and I squeezed a workout in on my off days from running – if at all. This was probably my first mistake as we know of the benefits that resistance training has for running performance and health of a runner. I just wasn’t consistent enough in my resistance training during my half marathon preparation. I also probably should have modified my resistance training sessions to include some more plyometrics. I mean, I even made videos about recommended strength exercise for runners for our running rehab course with Benoy Mathew. Oh well….

As the weeks went by, I honestly started to enjoy running. My mileage went up and I explored new running routes which kept the runs interesting and I was again fascinated by our bodies ability to adapt to different training stimuli. Being able to run both longer distances and a faster pace: Running more than 10K for the first time as far as I can remember, then hitting a sub 50-minute 10k was just as satisfying as hitting a new squat PR.

I did 3 runs per week:

- An easy short distance run at the start of the week

- A medium distance run midweek with a focus on my desired halfmarathon pace while keeping my RPE in check so I paid close attention to my breathing and average heartrate

- A long run over the weekend to build up overall mileage

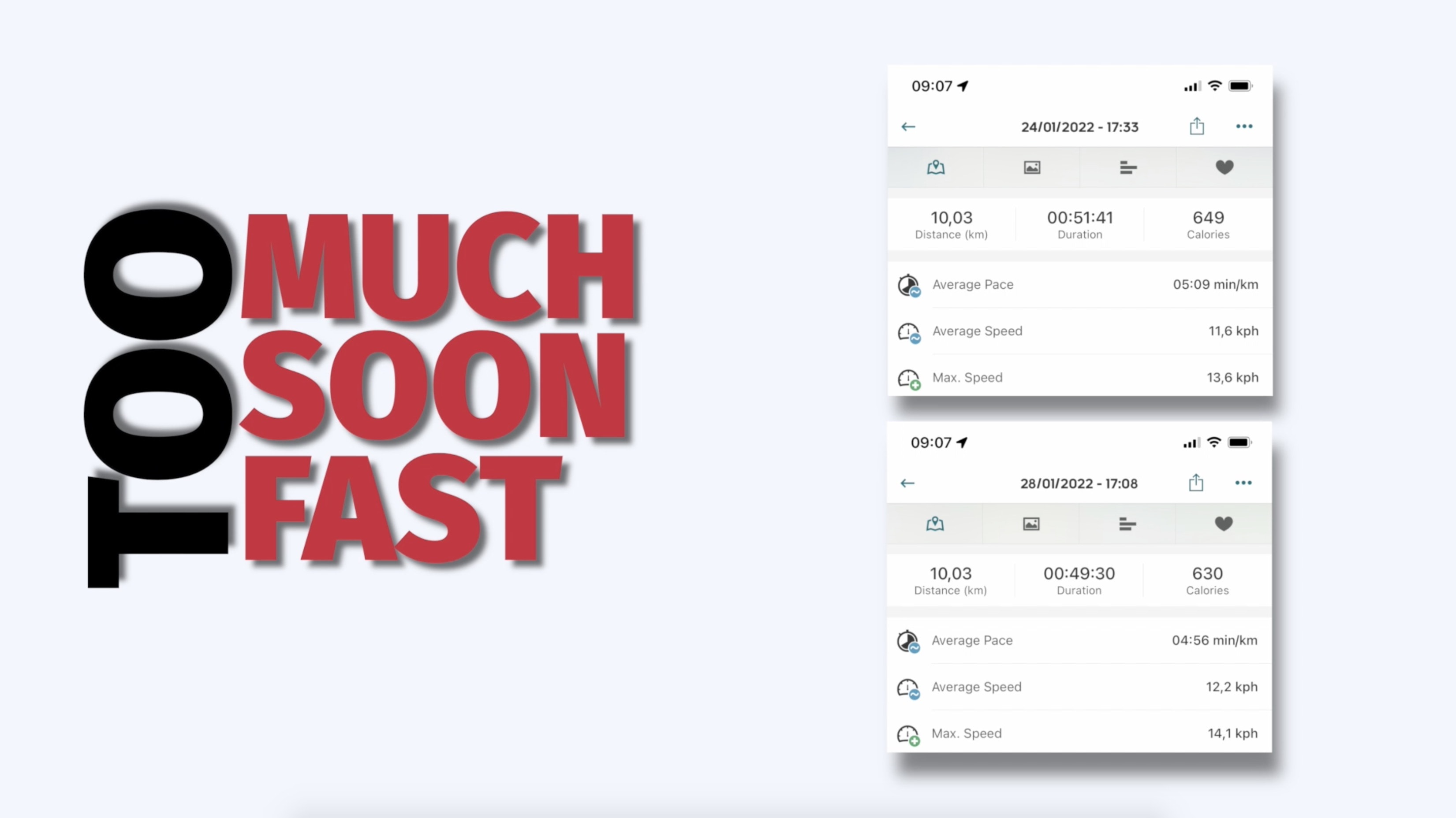

Then February 2022 comes around. Two months until raceday and this is when I made the classic mistake of doing too much, too soon, too fast. The trifecta of getting injured.

Going too fast

I had completed the last two runs of January, both a 10k, at a significantly faster pace than usual. Or better yet, than I was supposed to. While I was training for a comfortable 5:20-5:30 pace for my half marathon, I ran a flat 5 and sub 5 minute pace. I went too fast.

Doing too much, too soon

Then, on the first Saturday of February I was supposed to run 17km, the longest distance I had ever run. It was a beautiful day and I again ran a new route. The run went really well and I became curious if I could complete 21km simply to prove to myself that I could run a half-marathon – just to ease my mind about the upcoming race. Adding an extra 4km to my run and overall weekly mileage was a silly thing to do. I did too much and I did it too soon. This was not according to plan and I know this is stupid and you’re probably thinking that as a PT I should know better. And you’re right.

I completed the full 21k at my anticipated half-marathon pace and I was super excited about this. It gave me confidence for raceday, however once back at home I could soon feel the repercussions of my actions. My left knee started to hurt and moving about the house was difficult. I knew that I overdid it, so I took some rest. But I felt proud that I could go the distance.

Plantar fasciitis

The next day, the soreness went down and after 2 days it was gone. I was relieved that I could pick up my training plan as scheduled and still fueled by my recent achievement I again went a little too fast on my next 2 short runs. Then on the third run of the week it hit me. Not the knee but my plantar fascia. After 2km I had to quit my run. To be honest with you, that’s when I panicked a little. I did not know if that would take me out of the race.

For the following week I threw the kitchen sink at it. I did take some NSAIDs to slow down cell proliferation and the analgesic effect was appreciated. I performed daily heavy slow resistance training including straight, and bent leg calf raises with extra stretch on the big toe, plantar fascia stretching, ankle dorsiflexion mobilisations and low-dye taping.

Luckily I didn’t have many symptoms during ADLs and I could even play tennis without seeing an increase in symptoms the following day. But I knew I would need to get back to running if I wanted to make it to Berlin. So I attempted a first 3k treadmill run on the 22nd of February and a 5k on the 25th which I could luckily complete, which was a relief. This gave me the confidence to get back on the road for running. I stuck with doing my rehab exercises on my off days from running and some auxiliary work before or after my runs. But that’s when I made a switch, which I think made things worse: my footwear.

My brother, who is an avid runner and works for Adidas, told me about a new shoe that had all the bells and whistles – lightweight, bouncy cushioning, and rods in the sole of the shoe for more propulsion. When I first tried it on it felt great. I made a conscious decision to build up my mileage in the new shoe gradually, so I only wore it for my short runs in the beginning.

Now in March, I could build up my runs back to 12k at a reasonable pace that I had anticipated for the half-marathon.

Two weeks go by and I lace up my new shoes and go out for an 8k run along my usual route from the office into the city along the Amstel river. I have to cross an intersection on that route and if there is one thing I hate while running, it is having to stop at a crosswalk. As I saw the pedestrian traffic light turn green in the distance, I started a midrun sprint to make it across the intersection in time. I would suffer the consequences a couple kilometers later. On the return leg of my run I suddenly felt a sharp pain on the outside of my left knee, which was also giving-way. I tried to shake it out but I just couldn’t. I was devastated as I had 2km to go back to the office. So I walked for a bit and tried to start running again but it took but 10m and my knee would give-way and hurt again. I knew this was likely ITB pain. To be honest, I panicked. I thought to myself, that’s it, I have to cancel the race in Berlin. Mind you, that’s 18 days before the race and I have not seen anyone magically rehabbing ITB in a couple of weeks. Gradual return to running commonly takes a good 4 weeks already.

My ITB Pain Rehab

I was familiar with Rich Willy’s work on ITB pain rehab and Kai made an elaborate video on the 5 stages of rehab for ITB pain. I wanted to do everything I can to get me into the best shape possible to hopefully make it across the finish line in Berlin on April 3rd. But I had to speedrun it.

Stage 1: This stage didn’t last long as pain when descending stairs subsided after 2 days. So I could move on to the load dominant phase. I did a combo of Bulgarian split squats, hip thrusts, and other hip abductor strengthening exercises and loading them up fast to see how far I could go. I did this every day along with uphill treadmill walking. On top I was still doing calf raises for my plantar fasciitis. I also pretty soon started plyometric exercises because I was aware of the energy storage capacity of the ITB and that I would need to train that. I was surprised how well those went. I did hops, jumps, and lateral skaters with resistance. But I didn’t go running for 13 days. However, I needed to know if I could return to running. It was now March 28th, 5 days until the race. So I arbitrarily said to myself: if I can run 5k today and 8k 2 days later, then I can make it across the finish line. I know – it sounds insane.

…I did anything to give myself the illusion that I was ready to run a half marathon despite everything that had happened.

But I was able to complete the 2 treadmill runs only feeling light symptoms. I was hyperaware of my knee the entire time though. Analyzing anything I was feeling. I paid close attention to my cadence, footstrike and step width. If I am honest with myself, I did anything to give myself the illusion that I was ready to run a half marathon despite everything that had happened. Oh well.

A quick pain story

And so I traveled to Berlin. I arrived two days before to be well rested for the race on Sunday. On Saturday I had a fascinating pain experience. I was so focussed on my knee that I suddenly felt things I hadn’t felt before: My left hamstring suddenly started hurting like I had a muscle strain. It felt like I had a sore patella too.

It felt like I was hypervigilant and that my “spam-filter” was allowing all sorts of messages through, which made my knee overly sensitive. My brain seemed to do anything to protect the knee to be in the best shape for the next day.

Raceday

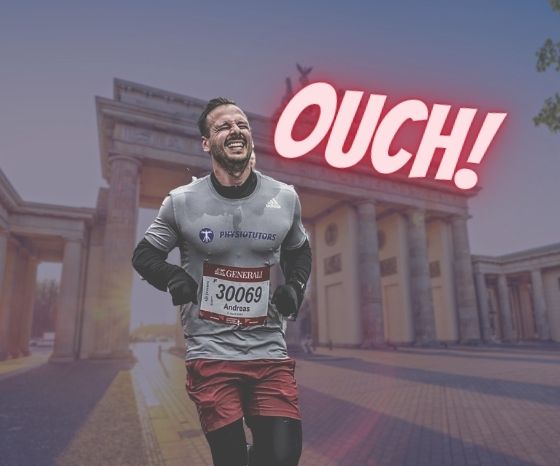

Raceday arrived and I was honestly nervous. I had a small breakfast and did a couple hip exercises with an elastic band to warm-up. We make our way to the starting line. I caffeinated, took some Ibuprofen, had my low-dye foot tape on and was full of adrenaline. And so I went on my way, still aiming for a pace of 5:30/km. Luckily it was quite a cold but sunny day, which was great for running. As this was my first official race I was in the last starting block of the over 30.000 runners that ran that day I had to make my way through the crowd of runners until I found my place in the pack that allowed me to run my anticipated and comfortable pace.

The first 5k go by and I am still doing fine. I get my first water and continue on, making sure I don’t overdo it with the pace and keep an eye out for my heart-rate. At 8K I take my first glucose gel which fuels me again and my knee is still doing fine. From here on out it’s the unknown. At the 12-13km point I can feel it a little but I take out a bit of pace and refuel at 15k with my second glucose gel. Also the crowd along the way really helps to distract me.

And much to my relief, my knee pain did not kick me out of the race. I did feel a pressure around the outside of my left knee the whole time but it never became that sharp pain I had felt before. In the context of the race it also wouldn’t have been advantageous to project pain. I gotta thank my beautiful brain for this. But it wouldn’t be a race if I didn’t go on an all out last stint for the remaining 3km pushing my average pace down to a 5:16/km.

So I got my medal, happy to have finished the race, and once the adrenaline had settled my knee went very unhappy with me. I could barely walk for the rest of the day and the better part of the next day when I had to travel back to the Netherlands.

Return-to-running

Coincidentally, the people from runeasi.ai reached out to us after having worked with our ACL rehab instructor and lower limb specialist Bart Dingenen on a project.

They develop technology using wearable sensors and artificial intelligence to provide personalized biomechanical insights to runners without the need for an expensive, indoor-only 3D motion lab.

They were kind enough to send us their wearable kit to try out and give feedback on and it came at the perfect time for me to include in my return-to-running rehab for my ITB pain. As I have already mentioned, the reason I think I got injured was the classic triad of doing too much, too fast, too soon, not regularly doing my other strength and conditioning work, and maybe the change of footwear that wasn’t ideal. But an aspect I hadn’t looked at thoroughly yet was my running biomechanics.

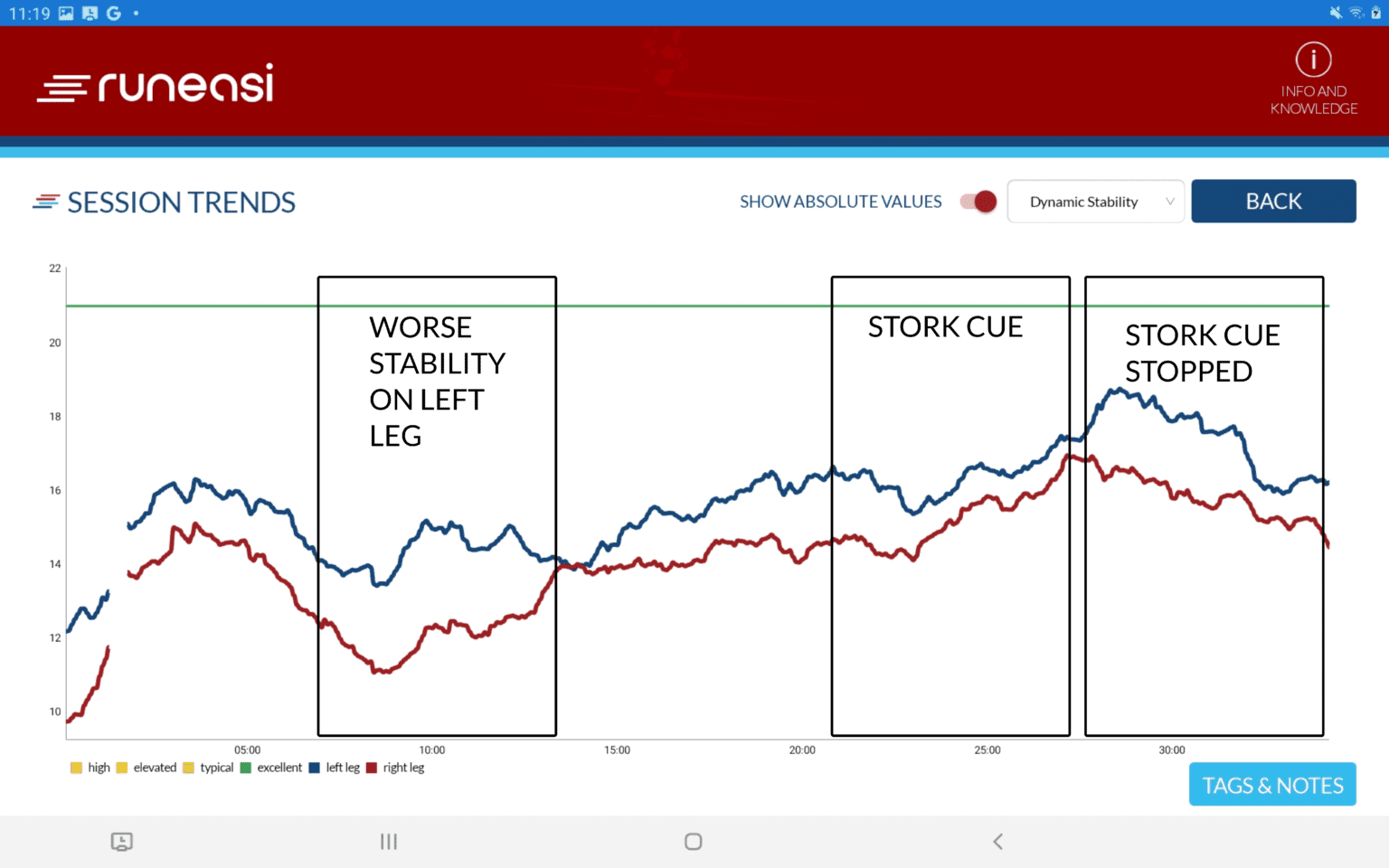

So I was back doing regular strength work in the gym and slowly returning to running with my goal being to at least be able to run a 10K a week. While I was returning to running I noticed that there seemed to be a tipping point around the 2-3km mark. That’s when I could noticeably feel my knee pain getting worse so that I would have to cease running shortly after. And I couldn’t seem to work my way beyond anything longer than 4km. I wanted to find out what was happening. Or better, does anything change in my running form or performance after 2-3km. That’s when I thought I’d give the runeasi wearable a shot. I set it up on our office tablet, hopped on our treadmill and started an analysis in “biofeedback” mode which would give me real time feedback on parameters such as: impact magnitude, impact duration, ground contact time, cadence, and dynamic instability.

there was a noticeable difference in readings between my left and right side which coincided with symptoms arising in my knee

So while I was running I cycled through the different parameters to see if anything was noticeable. I could already see that my impact was higher on the right side to which I thought: okay maybe I am subconsciously taking load off my left leg already. But it was only minor.

However, looking at the data on dynamic instability, I could notice while approaching 10 minutes of running that there was a noticeable difference in readings between my left and right side which coincided with symptoms arising in my knee. This was identical to what I felt on the road as well.

This is when I was trying different cues to see what could change my symptoms as well as the readings on the app. My cadence was alright, so shortening my strides wasn’t an option. I tried different step widths but that didn’t do the trick. But when I tried a different “hip strategy” as in the stork exercise during ground contact of my left leg this seemed to do the trick. I was actively focussing on engaging the lateral hip muscles, effectively “locking” the hip, and this led to a decrease in the readings of the wearable as well as improved my symptoms. This was an eye opening moment because when I stopped this strategy, symptoms would return and the readings on the app would show it too and when I focussed on deploying my newfound strategy again, they changed for the better. I continued running until I hit 5K and then stopped because I felt confident that I had found what to work on to get my mileage back up without aggravating my symptoms. Personally, this was very valuable information, as this appeared to be the missing piece in my rehab that I otherwise wouldn’t have found out about. I was doing progressive strength work (as previously explained), had good strength markers on both limbs, included plyometrics, and graded return-to-running but the latter didn’t want to progress. I know that rehab is not linear but I was making good strength gains but my running distance just didn’t want to catch up.

Usually, I don’t get a lot of muscle soreness anymore from training but the day following my running analysis session where I found a new hip strategy I could really feel soreness in my lateral hip muscles. For me that was an indicator that I may have found a weak link in my running biomechanics, which I will need to work on. You probably want to know how I did that?

So did I do: A) Daily sets of hip abductions B) 3×100 Hip stork exercises C) E-stim to my gluteus medius D) I just went running

The answer? I just continued with a graded return to running. But I focussed on my hip strategy, to “engage” my hip muscles more specifically during ground contact of my stance leg. Yes, I can work on strengthening my hip with exercises, but I was doing that already. I am doing double and single leg exercises, gradually overloading those, but the cyclical nature of running is different from more static gym based exercises. So I focussed on training my form during running. And this allowed me to finally break through running 5,6,7,8 and finally run 10K again at a reasonable pace and without flare-ups of my knee pain. At first I was not symptom free but the symptoms didn’t prevent me from finishing my runs nor did they affect my ADLs and they calmed down within 24h. I did not feel a sharp pain but more of a pressure-like feeling – if at all. You could say that I was poking the bear but not waking it up during my rehab. I am now symptom free.

My current training plan

So here is what my current training looks like: Monday to Friday I do strength training with 2 leg sessions per week and some core exercises, I play tennis 1-2 times a week, and I go for a run on the weekends and run between 7-10km. That’s it.

I am taking my time with this and I am not saying that this is the best way to do it but it fits with my work and other sports/activities. I am not making running a priority as I enjoy lifting and tennis more but I want to keep 1 run a week in my program. So that’s why my program looks the way it is.

Now, you might be asking yourself how I would teach this strategy to a patiënt. I don’t think there is a verbal cue that I could give to the patiënt and they could put that into action on the spot. Running is too fast of a movement for that. I would probably first regress off the treadmill and start with hip hikes or the stork exercise in a static environment. Then try to do it cyclically and the patient will feel the hip engaging more, then try it at slow walking speed and build up speed gradually.

Final thoughts

So there you have it. My journey from 0km a week to the first half-marathon in 5 months. How I got injured along the way and how I did my rehab. Rehabbing your own injury as a physio is always a great learning moment and these injuries become the best injuries to treat with others as you can better relate to their situation. And yes, I have made the same mistakes that a patient usually makes too – doing too much, too fast, and too soon. Even though you’d think I should know better. But I am human too and can get carried away by the achievements I have made and thinking I can do anything. Sticking to a plan is hard. Remember that when working with your patients as well.

Andreas Heck

Co-Founder

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.