‘I’m active enough in my job.’ Why is occupational physical activity not enough?

Sure, we copied that title from the recently published editorial by Rilind Shala, because it says it all. In this blog post, we take a look at the evidence to answer this question.

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a major cause of detrimental health and increases the risk of all-cause mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. Many people consider their levels of physical activity during working hours as sufficient or at least contributing to this recommendation. But is this statement justified? Although we cannot speak for everyone here, you may be surprised to hear that in most cases, the levels of physical activity during occupational activities are not enough to fulfill the recommendations. In some cases, occupational physical activity may even be detrimental to a workers’ health. In this blogpost we’ll dive into some research to discuss this statement.

Physical activity is promoted for its health-enhancing benefits in healthy people. People with unhealthy lifestyle habits are promoted to engage in higher levels of physical activity to counteract the effects of their lifestyle on health outcomes. This working mechanism of physical activity is through reducing levels of inflammation, attenuating blood pressure, lipid profile, and by improving strength and cardiorespiratory fitness. Higher levels of physical activity are associated with risk reductions of up to 35% for all-cause mortality, 55% for cardiovascular disease, and 30% for type 2 diabetes.

Many people have active jobs: those in construction, cleaning, health care, farming, and manufacturing for example. Often, a large proportion of their day is spent on their feet, carrying things, walking, going up and down stairs, bending over and so much more. But, less heavy lifting and lower intensity work like housekeeping and childcare can be considered here as well. Despite them being very active throughout the day, often these workers get confronted with poor health.

Paradoxically, there is evidence that occupational physical activity (OPA) can have adverse health effects. In the umbrella review of Cillekens and colleagues in 2020, evidence pointed to an association between high levels of OPA and all-cause mortality (in men), depression, anxiety, osteoarthritis, and sleep quality and duration. Some studies report about the risk for overuse injuries, fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, and some types of cancer. The observational cohort study by Bonekamp et al. in 2022 compared leisure-time and occupational physical activity and its effects on cardiovascular health in those with established cardiovascular disease. They found that being physically active in your spare time is strongly protective against all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, and type 2 diabetes risk. This was not found when the authors looked at higher levels of OPA. Instead, higher levels of OPA seemed to be associated with an increased risk of these outcomes. This is often referred to as the physical activity paradox.

Being physically active in your spare time is strongly protective against all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, and type 2 diabetes risk. This was not found in high occupational physical activity (OPA) levels. Instead, higher levels of OPA seemed to be associated with an increased risk of these outcomes. This is often referred to as the physical activity paradox.

How can this paradox be explained?

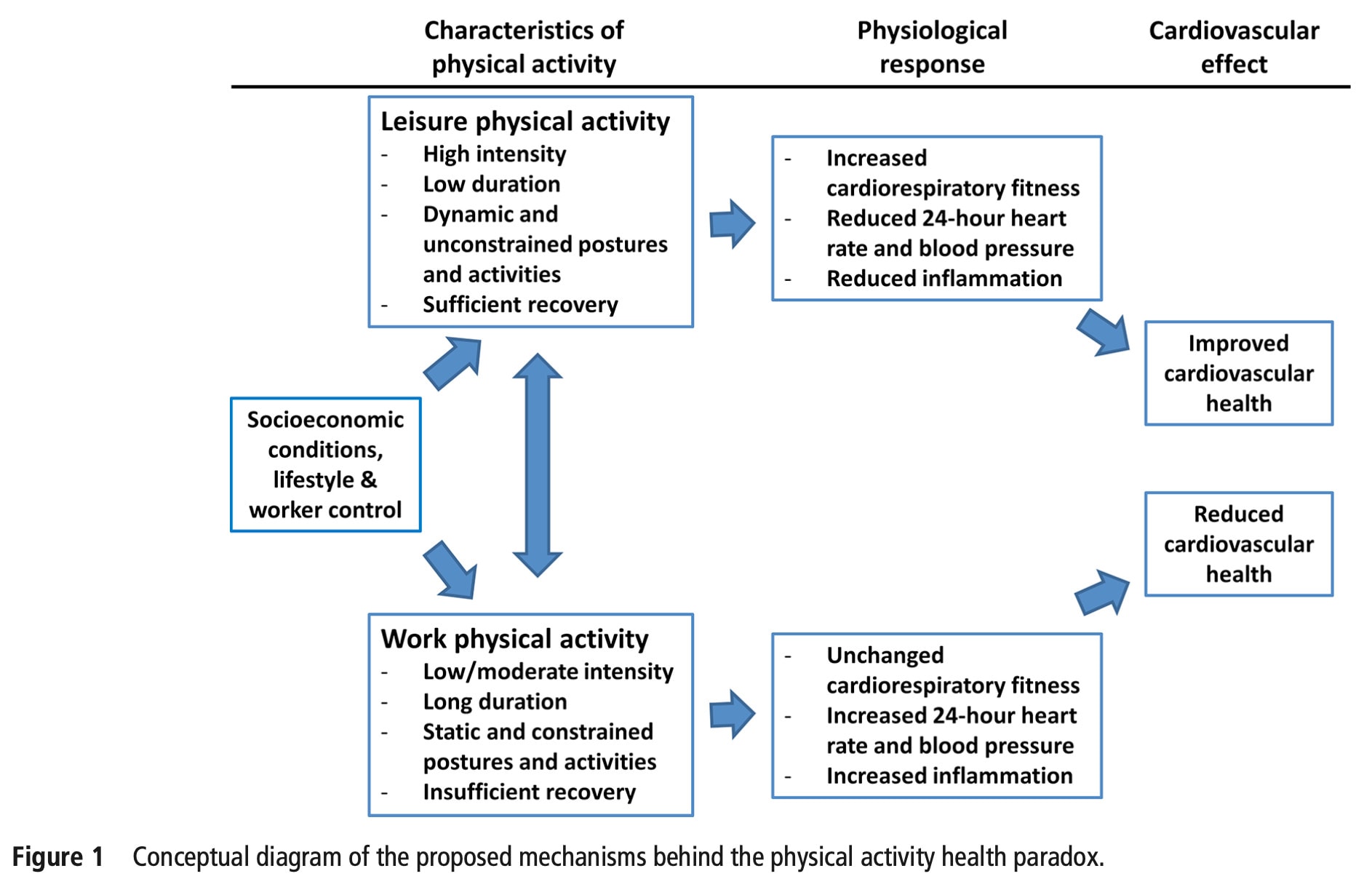

The physical activity paradox is thought to be driven by some of these underlying mechanisms, as proposed by Holtermann et al. in 2018:

- OPA is of too low intensity or too long duration for maintaining or improving cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular health.

- OPA elevates 24-h heart rate and levels of inflammation and in case of heavy lifting or static postures, elevates 24-h blood pressure

- OPA is often performed without sufficient recovery time

- OPA is often performed with low worker control

In contrast, leisure-time physical activity is generally performed at a moderate to high-intensity level during relatively short periods of time, with adequate periods of rest in between. Moreover, this is most often a type of physical activity that people want to do because they like the activity/sport. In contrast, OPA is performed for relatively long periods of time during the day, for several consecutive days, and requires often standing in specific postures, carrying things, twisting and bending repetitively, and lifting or handling high loads. As the loads accumulate throughout the day and are repeated the next day, a short recovery period between the end of the work day and the beginning of the next is evident. It isn’t surprising that this can be further influenced by poor sleeping habits, stress, etc.

Is occupational physical activity to blame for poor health?

Luckily, the answer is no. We cannot state that this risk comes from high levels of OPA alone. The evidence about the physical activity paradox comes from mostly observational cohort studies. These studies have the risk of containing many confounding variables. Furthermore, there is evidence available that points to the favorable effects of high levels of OPA. For example, in a study by Fan et al. (2018) from China, high levels of OPA had positive health effects compared to low levels of OPA in males. This effect was corrected for many confounding factors, under which age, education, marital status, alcohol use, smoking, diet, body mass index, diabetes, family history of heart attack or stroke, blood pressure, and all other domains of physical activity were the most important. The evidence also found favorable outcomes in those with high levels of OPA, luckily. It could be protective against cancer, ischaemic stroke, coronary heart disease, and mental health. This is certainly an area to be researched further.

It should be noted that in many cases, socioeconomic variables influence the outcomes. Think of people who have lower levels of job autonomy. Or those with low income, where possible lifestyle factors further contribute to the increased health risks. Furthermore, the influences of confounding factors may have changed over the years, and older observational studies may not be as accurate today. For example, over the years, people tend to smoke less. On the other hand, body mass index may have increased in certain countries. A large limitation lies also in the fact that many of these observational studies use self-report questionnaires that may be subject to many biases and tend to be of low validity.

What should we learn from this blog post?

Most importantly 2 things:

- Engage in leisure-time physical activity as occupational physical activity should not be regarded as a substitute for physical activity in leisure time!

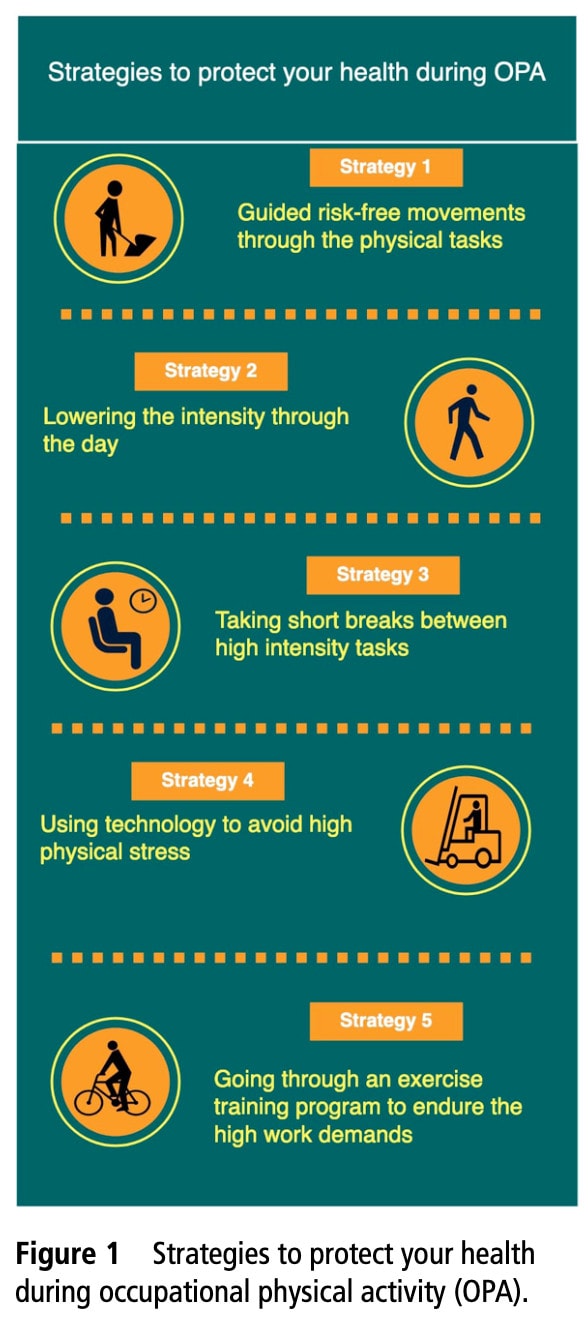

- Protect your health during occupational physical activity. Five strategies have been proposed by Shala et al. (2022), as depicted here below.

Therefore being physically active besides your job, even when you already have health issues, remains one of the most important things to remember from this blog post. Remember that we, as physiotherapists, spend a lot of time on our feet, and should engage in enough leisure-time exercise as well! 😉

I hope you enjoyed this post, Ellen

References

Shala R. ‘I’m active enough in my job.’ Why is occupational physical activity not enough? Br J Sports Med. 2022 Aug;56(16):897-898. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104957. Epub 2022 Mar 11. PMID: 35277394; PMCID: PMC9340008. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35277394/

Holtermann A, Krause N, van der Beek AJ, Straker L. The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Feb;52(3):149-150. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097965. Epub 2017 Aug 10. PMID: 28798040. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28798040/

Coenen P, Huysmans MA, Holtermann A, Krause N, van Mechelen W, Straker LM, van der Beek AJ. Towards a better understanding of the ‘physical activity paradox’: the need for a research agenda. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Sep;54(17):1055-1057. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101343. Epub 2020 Apr 7. PMID: 32265218. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32265218/

Cillekens B, Lang M, van Mechelen W, Verhagen E, Huysmans MA, Holtermann A, van der Beek AJ, Coenen P. How does occupational physical activity influence health? An umbrella review of 23 health outcomes across 158 observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Dec;54(24):1474-1481. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102587. PMID: 33239353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239353/

Bonekamp NE, Visseren FLJ, Ruigrok Y, Cramer MJM, de Borst GJ, May AM, Koopal C; UCC-SMART Study group; UCC-SMART study group. Leisure-time and occupational physical activity and health outcomes in cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2022 Oct 21:heartjnl-2022-321474. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-321474. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36270785. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36270785/

Ellen Vandyck

Research Manager

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.