Strong, steady, and straight: Physical activity and exercise recommendations for osteoporosis

Introduction

Fractures of the hip and spine are frequently seen in older adults. Especially in people with osteoporosis, falls may be an important contributor. Some people become afraid of falling and adopt maladaptive behaviors as they think it gives them more stability. Of course, osteoporosis should be prevented to avoid having an increased risk of fractures upon falling. Exercise is the treatment to improve bone strength and can help to become stronger, which may help reduce the risk of falling. But is it too late when osteoporosis is already evident? This blog dives deeper into the safety of exercise in people with osteoporosis and takes a look at exercise recommendations for osteoporosis. Further, it discusses how to become stronger, and steadier and stand up more straight.

Is it safe to exercise with osteoporosis?

Often, people become afraid to exercise and therefore participate less in sports and exercise activities. Also, healthcare providers may be unsure whether it is safe to prescribe exercise and avoid giving recommendations about exercise. Of course, this does not help someone who already has an increased risk of falls or osteoporosis. So what is known in the literature?

A systematic review by Kunutsor et al. (2018) investigated the adverse events and safety issues associated with exercise and physical activity among adults with osteopenia and osteoporosis. Of 62 trials, 11 reported fractures during the study period, but these were rarely attributed to the interventions themselves. Very importantly, those engaging in physical activity and exercise had an overall fracture incidence of 5.8%, but those people included in the control groups had a 9.6% fracture incidence. This study found no evidence of symptomatic vertebral fractures associated with impact exercise or moderate to high-intensity muscle strengthening. This finding was supported by the LIFTMOR trial by Watson and colleagues in 2019, where high-intensity exercise did not cause vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass. Equally, in the LIFTMOR-M trial by Harding et al. (2021), where men with osteopenia and osteoporosis were included, the preliminary findings point to an improvement in thoracic kyphosis and no fracture risk after participation in high-intensity resistance and impact training. In the B3E-feasibility trial of Giangregorio et al. from 2018, twelve months of home exercise to improve strength, balance, and physical activity in older women who previously sustained a vertebral fracture found no differences in falls and fractures between the control and exercise groups. So trials aiming at increasing bone mineral density indicate that exercise is safe to be conducted in people who already have diminished bone density (osteopenia) or osteoporosis.

It should, however, be noted that not every trial reports adverse events. But in those who do, evidence points to little evidence of harm, including fractures, occurring while participating in exercise or physical activity.

How can I become stronger?

The combination of impact and progressive resistance training best promotes bone strength, as stated in several guidelines. But what are the exercise recommendations for osteoporosis?

Ideally, it is supervised as it helps with good execution (using the best technique) and minimizes injury risk. A good technique can be learned using lower loads, but once the individual is able, loads should be progressively increased up to 80-85% of the 1 Repetition Maximum (1RM). The most convenient way may be to exercise at 8-12 RM, as this is easier to perform and prescribe at home. Further, the recommendations point to targeting strengthening exercises at the major muscle groups of the arms, legs, chest, shoulders, and back. The Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise for the prevention and management of osteoporosis recommends performing weighted lunges, hip abduction and adduction, knee extension and flexion, plantar-dorsiflexion, back extension, reverse chest fly and abdominal exercises while avoiding loaded spinal flexion. Ideally, these are performed two or three days per week.

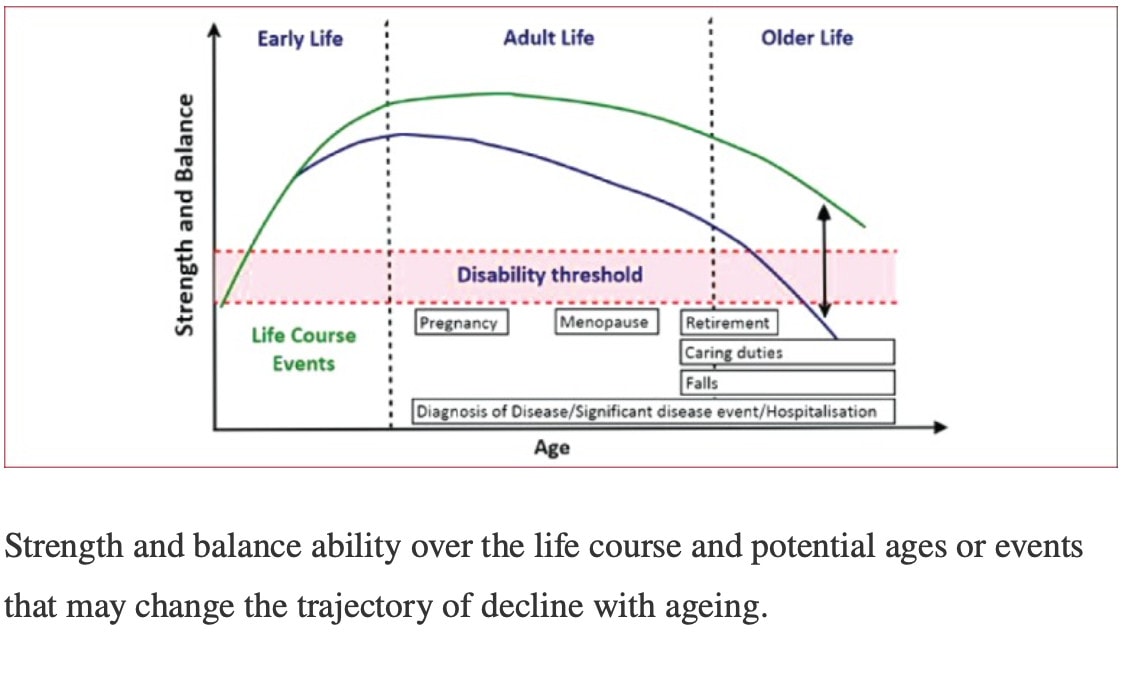

Okay but not everyone can go to the gym or is motivated to perform resistance exercises at home. Skelton et al. (2018) showed concerning evidence that 69% of men and 76% of women are not meeting the strength and balance guidelines (of 2 or more sessions/week). As the ages of 40-50y are especially important to maintain strength and reduce the downward cycle, and the ages over 65 years are especially important to preserve balance and strength and maintain independence, other types of exercise and physical activity can be undertaken. Therefore, it is better to encourage other types of physical activity to the individual’s preferences. Doing some is always better than doing none, as we previously outlined in another blog post.

In brief, weight-bearing or impact activities like dancing, Pilates, yoga, running, aerobics, ball games,… can be recommended, especially because they do not require specialized equipment and may be more enjoyable to most people. The best is to perform impact activities 4-7 days per week and every session should include at least 50 jumps, in 3-5 sets of 10-20 repetitions with 1-2 minute rest in between. The recommended loading is high for those without osteoporosis: more than 4 times body weight. Those at moderate risk of osteoporosis could do with 2-4 times body weight.

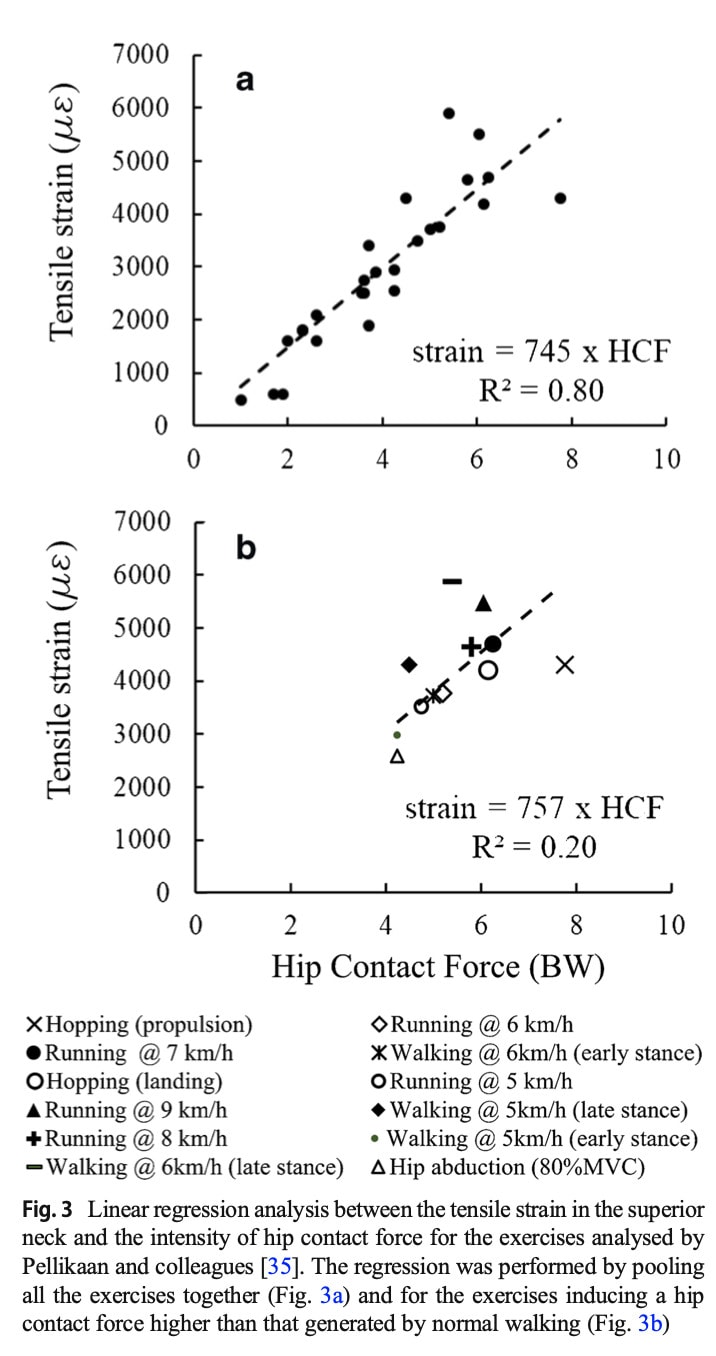

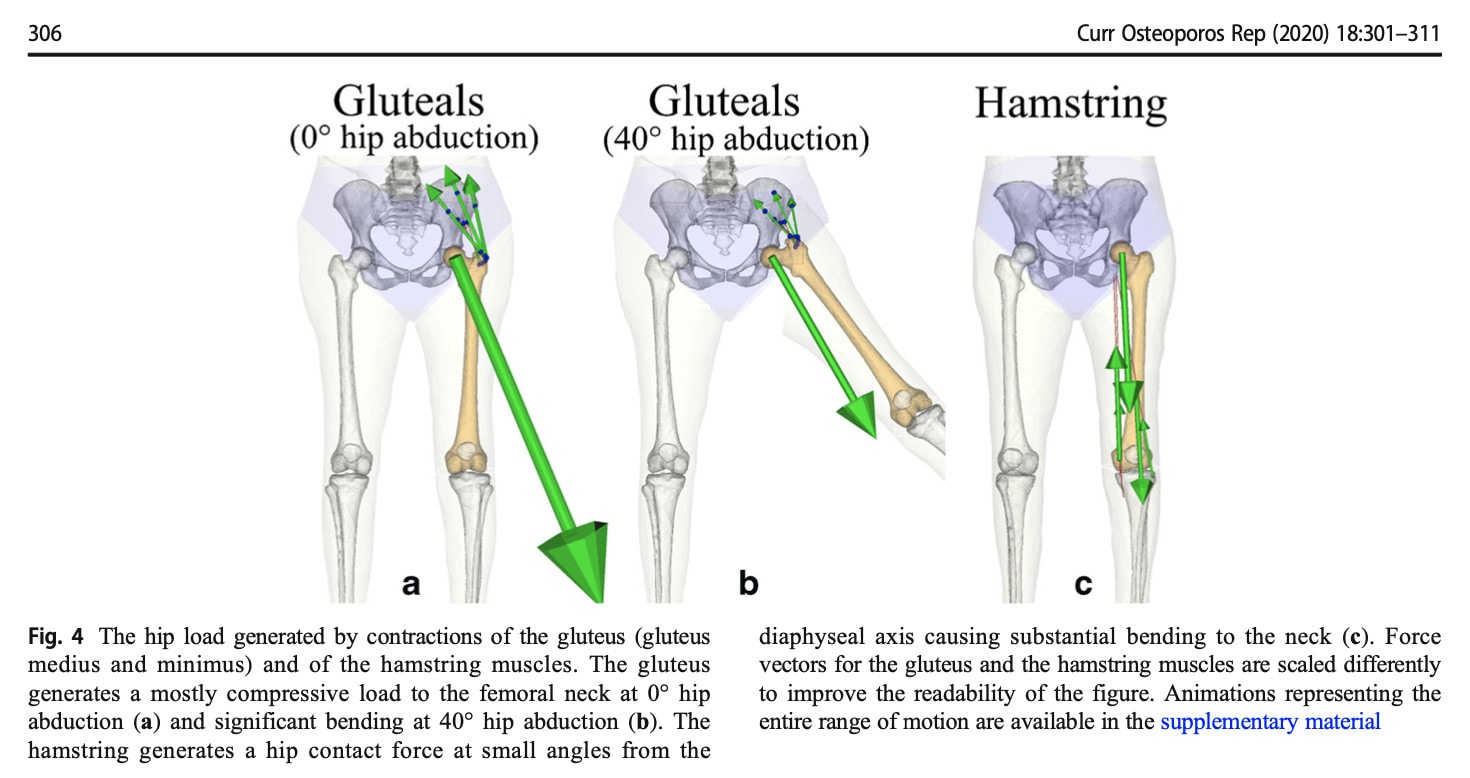

How do we know how much impact an activity gives? The study of Martelli et al. in 2020 may help us out. This study investigated the forces induced at the hip joint during different activities. As you can see, hip abduction at 80 percent of the maximal voluntary contraction and walking gives around 4 times body weight hip contact force. Running at low speeds (5-6 km/h) produces around 5 times body weight contact forces. Landing from a hop and running at about 7-9 km/h give around 6 times the body weight of impact force at the hip. Hops for distance create the highest contact forces with around 8 times body weight.

Exercise recommendations for osteoporosis further point to implementing impact activities, such as jumps, skipping, hopping, running, and impact during dancing activities with around 50 moderate impacts (with rest pauses) on most days. A little more prudence is recommended in those already having sustained vertebral fractures or multiple low trauma fractures (so in general, those with general bone fragility and a higher risk of fractures). Here the recommendations point to building up the impact to moderate intensity impacts with taking into consideration the number of vertebral fractures and symptoms, the co-occurrence of other medical conditions, and their physical fitness and previous experiences with impact activities.

The following figure nicely presents the impact of different muscles’ actions at the hip.

How can I become steadier?

Of course, we want to avoid falling in people with osteoporosis and we want to make sure they can participate in their daily activities without having an increased risk for falls. We know from a large Cochrane review that targeted strength and balance training can prevent falls. The review pointed to a rate ratio of 0.77 which means that exercise was able to reduce the rate of falls by 23%. Equally, exercise can reduce the number of people experiencing a fall by 15%. But how do we get there?

Exercise recommendations for osteoporosis point to individualized and supervised exercise training that is highly challenging and conducted for 3 hours per week over at least 4 months. After these four months, it should allow an individual to participate in more challenging weight-bearing activities like brisk walking (we will dive into this a bit further in this blog post). That is a lot of training, right? Those who are unable to participate in such training programs are advised to conduct other activities such as Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and pilates at least twice a week in line with physical activity guidelines.

There is something to say for strengthening the muscles of the back. We will dive into this in the following section. Yet, another interesting finding is that an increased kyphosis can have a negative influence on someone’s fall risk. The reason is that the center of mass is more lying in front of the feet than in someone who is standing more upright. So to become steadier, one should target the strength training to the back extensors and try to modify kyphotic postures.

How professionals communicate the benefits of falls prevention exercise is important. Most people do not perceive themselves as fallers or as frail.

How can I stand up more straight?

Someone with an increased kyphotic posture (with or without osteoporosis) might come up to your consultation with the goal to stand up more straight. It does not only help with reducing their risk of falls and fractures. It may also be valuable to reduce pain and the risk of vertebral fractures. Exercise previously has been shown to improve posture through back extensor strengthening. Back extensor strength is further thought to cause improvements in standing balance.

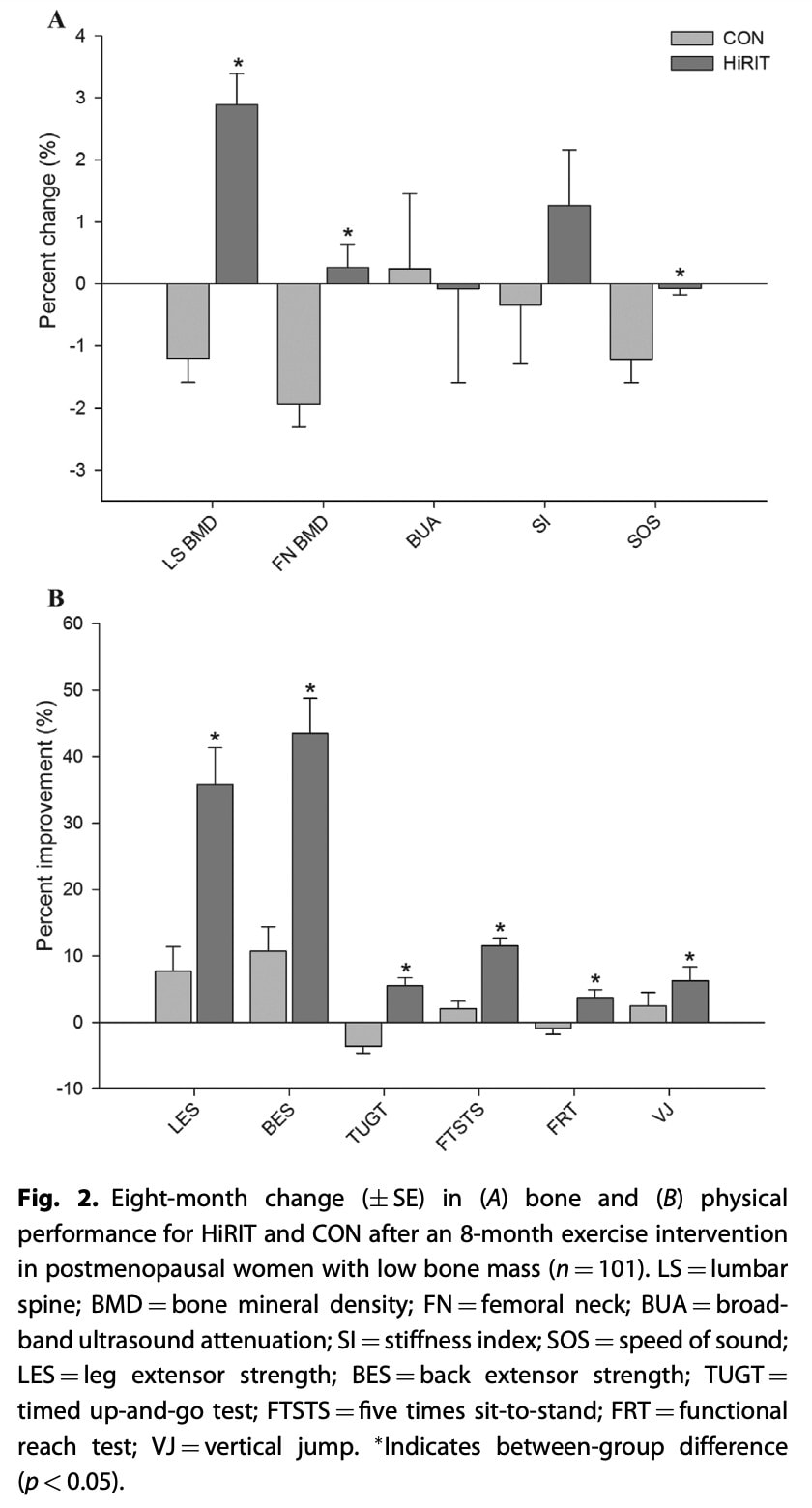

How to improve someone’s posture then? We can take a look at the LIFTMOR trial, which led to an improvement in thoracic kyphosis, besides other important achievements. Here, postmenopausal women with low bone mass (T-score < -1.0, screened for conditions and medications that influence bone and physical function) were recruited and randomized to either 8 months of twice-weekly, 30-minute, supervised high-intensity resistance and impact training (5 sets of 5 repetitions, >85% 1 repetition maximum) or a home-based, low-intensity exercise program which served as the control treatment. The high-intensity resistance and impact training was superior to the control intervention for increasing the participants’ height by 0.2cm (+/-0.5cm). The trial by Katzman in 2007 led to an improvement in kyphosis by 5-6°. Importantly, bone mineral density in the lumbar spine and femoral neck and the cortical thickness of the femoral neck increased and importantly caused superior effects in all functional performance measures in the LIFTMOR trial. What type of training did they do, I hear you think.

Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine

Become confident in screening, assessing and treating the most common pathologies in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine based on the very latest evidence from 440 research articles.

In the LIFTMOR trial, surprisingly, they performed 4 exercises only. Three resistance exercises: deadlifts, overhead presses, and back squats for 5 sets of 5 repetitions, at 80-85% of their 1RM. They supplemented these exercises with “jumping chin ups with drop landings”. Here the participants hold on to an overhead bar and were instructed to jump as high as possible while simultaneously pulling themselves up as high as possible. At the peak of this jump, the participants were asked to let go of the bar to land on their feet “as heavily as comfortably possible”. Before the trial progressed to these exercises, the first month ensured the participants learned good technique and were able to perform bodyweight exercises and low-load variants of these exercises. But importantly, the trial stated that all participants were able to do these exercises by 2 months. Very importantly, there was only 1 adverse event recorded: minor lower back spasms which led to missing 2 out of 70 exercise sessions.

In the Katzman study, they performed high-intensity, progressive resistance exercise and stretching. Exercises included thoracic extension, shoulder flexion and hip extension stretching, trunk extension and scapular muscle strengthening, transversus abdominus stabilization, and postural alignment training. For spinal extension strengthening, participants performed prone trunk extension to neutral against gravity, starting without weights and progressing through a series of three prone postures prior to adding hand-held dumbbells. Spinal rotation and extension strengthening exercises were performed side-lying with resistance and quadruped with weights.

How can I exercise safely?

To enhance the safety of the training program, some precautions can be taken. First and foremost, exercise recommendations should be tailored to the individual, bearing in mind other comorbidities. The sessions should ideally be supervised by a healthcare practitioner to ensure proper technique and progressions are made. Like any exercise program, a gradual but progressive build-up is required. But, the higher the dose and the longer the duration of the intervention, the greater change is observed, especially in people over 70 years of age. From the trials and studies we discussed here, some other precautions can be taken. In the LIFTMOR-M trial which was based on the same trial we discussed above, but conducted in middle-aged and older men with low bone mineral density, the high-intensity progressive resistance and impact training program was compared with machine-based isometric axial compression training. In the small sample of 40 participants, there were no incident vertebral fractures nor progression of prevalent vertebral fractures in the high-intensity training over the 8 months. But, 5 incident fractures of thoracic vertebrae occurred and one wedge fracture progressed for those in the isometric axial compression group. So maybe, it would be safe to avoid axial compression in this group of people until more evidence is available. Further, the systematic review by Sherrington et al. in 2017 found an increased fracture risk in people already at risk for falling when they participated in a brisk walking program. Therefore, they advise participants to engage in strengthening and to perform balance exercises prior to starting a brisk walking program. Two studies by Sinaki reported fractures occurring due to some yoga postures and therefore they recommend avoiding extreme, sustained, or repeated end-range positions or loaded flexion exercises.

Take home messages

So to conclude, everyone with osteoporosis may benefit from physical activity as the benefits in general outweigh the risks. Ideally, a program mixing up resistance exercises and impact activities should be prescribed. It is recommended to place the emphasis of the exercise training on “being able to continue” activities and exercise rather than to prohibit exercise. Apart from minor adverse effects like transient muscle soreness and joint discomfort, exercise is safe and effective to perform. With exercise, the aim is to prevent the premature occurrence of the disability threshold, as can be visualized in the picture from Skelton above. But most importantly, let people engage in activities they enjoy!

I hope you enjoyed this blog! – Ellen

References

Brooke-Wavell K, Skelton DA, Barker KL, Clark EM, De Biase S, Arnold S, Paskins Z, Robinson KR, Lewis RM, Tobias JH, Ward KA, Whitney J, Leyland S. Strong, steady and straight: UK consensus statement on physical activity and exercise for osteoporosis. Br J Sports Med. 2022 May 16;56(15):837–46. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104634. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35577538; PMCID: PMC9304091. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35577538/

Kunutsor SK, Leyland S, Skelton DA, James L, Cox M, Gibbons N, Whitney J, Clark EM. Adverse events and safety issues associated with physical activity and exercise for adults with osteoporosis and osteopenia: A systematic review of observational studies and an updated review of interventional studies. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018 Dec 1;3(4):155-178. doi: 10.22540/JFSF-03-155. PMID: 32300705; PMCID: PMC7155356. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32300705/

Watson SL, Weeks BK, Weis LJ, Harding AT, Horan SA, Beck BR. High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2018 Feb;33(2):211-220. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3284. Epub 2017 Oct 4. Erratum in: J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Mar;34(3):572. PMID: 28975661. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28975661/

Watson SL, Weeks BK, Weis LJ, Harding AT, Horan SA, Beck BR. High-intensity exercise did not cause vertebral fractures and improves thoracic kyphosis in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass: the LIFTMOR trial. Osteoporos Int. 2019 May;30(5):957-964. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-04829-z. Epub 2019 Jan 5. PMID: 30612163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30612163/

Harding AT, Weeks BK, Lambert C, Watson SL, Weis LJ, Beck BR. Exploring thoracic kyphosis and incident fracture from vertebral morphology with high-intensity exercise in middle-aged and older men with osteopenia and osteoporosis: a secondary analysis of the LIFTMOR-M trial. Osteoporos Int. 2021 Mar;32(3):451-465. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05583-x. Epub 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32935171. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32935171/

Giangregorio LM, Gibbs JC, Templeton JA, Adachi JD, Ashe MC, Bleakney RR, Cheung AM, Hill KD, Kendler DL, Khan AA, Kim S, McArthur C, Mittmann N, Papaioannou A, Prasad S, Scherer SC, Thabane L, Wark JD. Build better bones with exercise (B3E pilot trial): results of a feasibility study of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of 12 months of home exercise in older women with vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2018 Nov;29(11):2545-2556. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4652-0. Epub 2018 Aug 8. PMID: 30091064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30091064/

Beck BR, Daly RM, Singh MA, Taaffe DR. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017 May;20(5):438-445. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.10.001. Epub 2016 Oct 31. PMID: 27840033. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27840033/

Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important? J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018 Jun 1;3(2):74-84. doi: 10.22540/JFSF-03-074. PMID: 32300696; PMCID: PMC7155320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32300696/

Martelli S, Beck B, Saxby D, Lloyd D, Pivonka P, Taylor M. Modelling Human Locomotion to Inform Exercise Prescription for Osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020 Jun;18(3):301-311. doi: 10.1007/s11914-020-00592-5. PMID: 32335858; PMCID: PMC7250953. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32335858/

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, Howard K, Clemson L, Hopewell S, Lamb SE. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 31;1(1):CD012424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2. PMID: 30703272; PMCID: PMC6360922. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30703272/

Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984 Oct;65(10):593-6. PMID: 6487063. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6487063/

Sinaki M. Yoga spinal flexion positions and vertebral compression fracture in osteopenia or osteoporosis of spine: case series. Pain Pract. 2013 Jan;13(1):68-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00545.x. Epub 2012 Mar 26. PMID: 22448849. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22448849/

Katzman WB, Sellmeyer DE, Stewart AL, Wanek L, Hamel KA. Changes in flexed posture, musculoskeletal impairments, and physical performance after group exercise in community-dwelling older women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Feb;88(2):192-9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.033. PMID: 17270517. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17270517/

Ellen Vandyck

Research Manager

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.