Lumbar Radicular Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment for Physiotherapists

Lumbar Radicular Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment

Introduction & Epidemiology

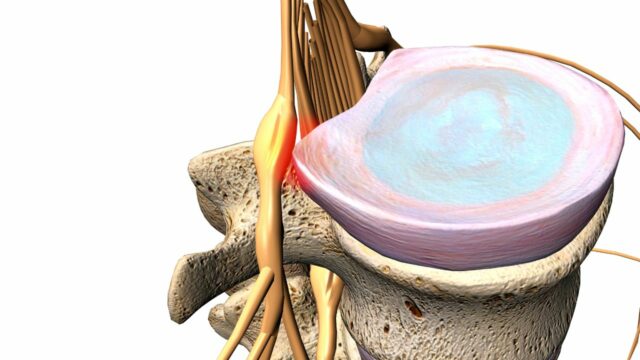

Lumbar radicular syndrome is the umbrella term encompassing radicular pain and/or signs of radiculopathy in the lumbar spine and sacrum. Even though “radicular pain” and “radiculopathy” are synonymously used in the literature, they are not the same. Radicular pain is defined as “pain evoked by ectopic discharges originating from a dorsal root or its ganglion”. Disc herniation (hernia nucleus pulposus, HNP), the most common cause, and inflammation of the affected nerve seem to be the critical pathophysiological process. Radiculopathy is yet another, distinct entity. It is a neurological state in which conduction is blocked along a spinal nerve or its roots (Bogduk et al. 2009). This leads to objective signs of loss of neurologic function such as sensory loss (hypoesthesia or anesthesia), motor loss (paresis or atrophy), or impaired reflexes (hyporeflexia). As disc herniations are by far the most common cause of lumbosacral radicular pain (90%, Koes et al. 2007), let’s have a closer look at facts & fiction around them:

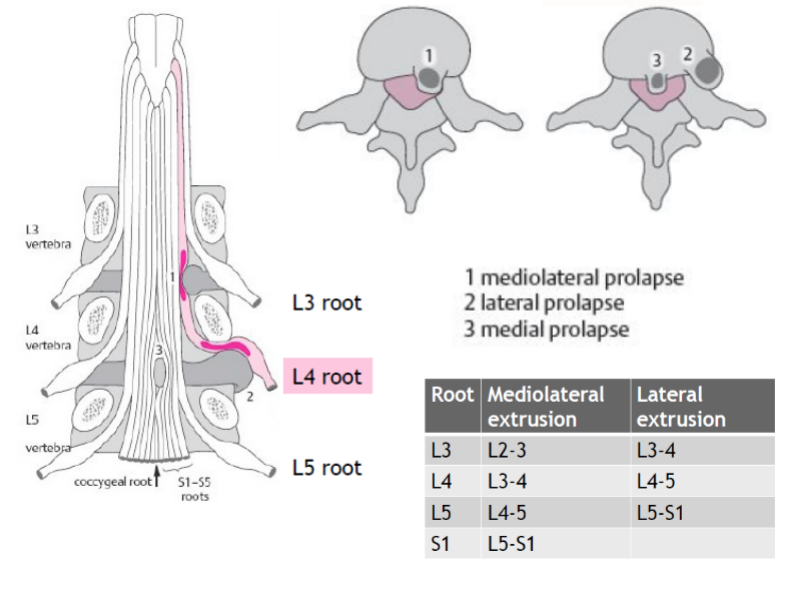

The prevalence of herniated discs is highest on levels L4-L5 and L5-S1 with both 45% of all cases. This is due to the fact that static and kinetic forces are the highest on these two levels. Furthermore, hernias on levels L3-L4 are reported to be less prevalent (5%), followed by an even lower prevalence on levels L2-L3 and L1-L2 (Schaafstra et al. 2015). In case of a disc herniation between L4-L5, the nerve root of L5 will be compressed and in the case of L5-S1, the nerve root of S1 is affected. This is due to the fact that most discus hernias present as mediolateral prolapses:

Epstein et al. (2002) have studied lateral disc herniations in detail. According to the authors, far lateral disc herniations represent 7-12% of all lumbar disc herniations and usually involve free fragments which have migrated superolateral to the disc space of origin. A far lateral disc herniation compresses the nerve root which exits at the same level; this is in contrast to classic mediolateral disc compression which affects the nerve root leaving at the level below (see illustration above). Most frequently far lateral disc herniations are encountered at either the L3-L4 or L4-L5 levels followed by L5-S1.

Epstein et al. (2002) have studied lateral disc herniations in detail. According to the authors, far lateral disc herniations represent 7-12% of all lumbar disc herniations and usually involve free fragments which have migrated superolateral to the disc space of origin. A far lateral disc herniation compresses the nerve root which exits at the same level; this is in contrast to classic mediolateral disc compression which affects the nerve root leaving at the level below (see illustration above). Most frequently far lateral disc herniations are encountered at either the L3-L4 or L4-L5 levels followed by L5-S1.Patients with far lateral disc herniations are typically in their mid-fifties, ranging from 50-78 years of age and often report extreme radicular pain associated due to a compromise of the dorsal nerve root ganglion in the lateral compartment. Leg pain is usually unremitting while back pain is often minimal.

Similarly to the cervical spine, a nerve root can also become entrapped between hypertrophied facet joints, a disc protrusion, spondylotic spurring of the vertebral body, or a combination of these factors. In these cases, we are talking about a lateral stenosis, which we will cover in the next unit amongst others. Other less likely reasons for radicular pain can be tumors, synovial cysts, infection, vascular abnormalities, or spinal stenosis, which we will cover in the following unit. You will learn how to recognize some of these red flags in the part on screening.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Signs & Symptoms

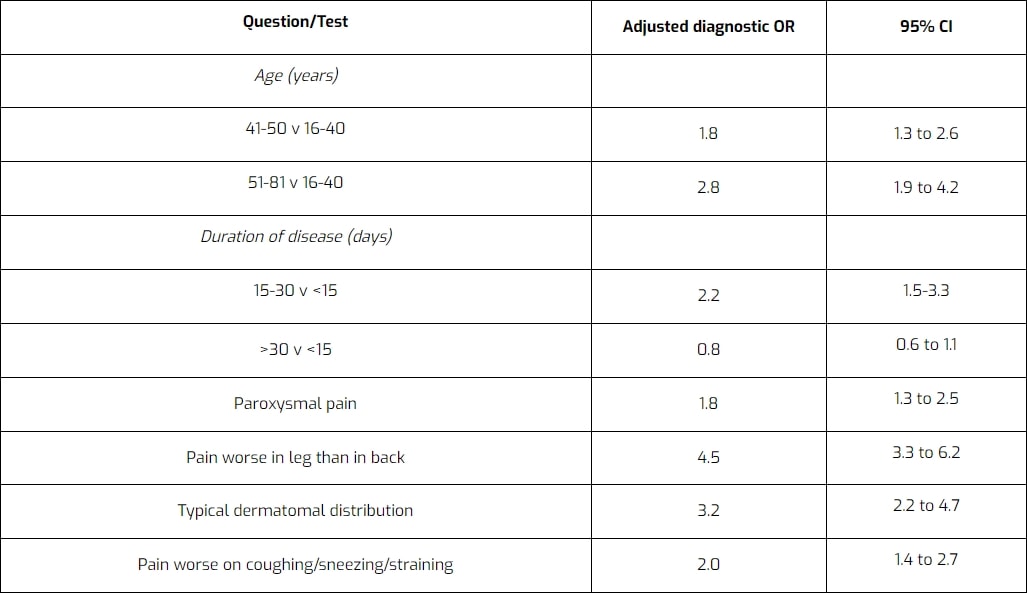

Similar to other pathologies, a thorough patient history can already point you in the right direction when considering the possibility of lumbosacral radicular syndrome. Vroomen et al. (2002) have evaluated different items during patient history regarding their accuracy to diagnose lumbosacral radicular syndrome. They have found the following items to be diagnostic for lumbosacral radicular syndrome due to disc herniation:

Examination

After patient history-taking, you might have formed the ICD (International Classification of Disease) hypothesis that your patient suffers from lumbosacral radicular syndrome. You can then further decrease your clinical uncertainty by performing physical tests to either exclude or confirm the hypotheses. The first test battery is focused on the reproduction or easing of radicular pain and/or paresthesia:

A more specific test to confirm the presence of lumbosacral radicular syndrome is the crossed SLR:

Other orthopedic tests to diagnose lumbar radicular syndrome are:

- Bowstring Test

- Slump Test

- SLR with proximal and distal initiation

- Slump Test with proximal and distal initiation

During the second part of your examination, you should perform a neurological examination focusing on the presence and degree of radiculopathy evaluating hyporeflexia, hypoesthesia, and paresis:

The following video on dermatome testing was derived from the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) form:

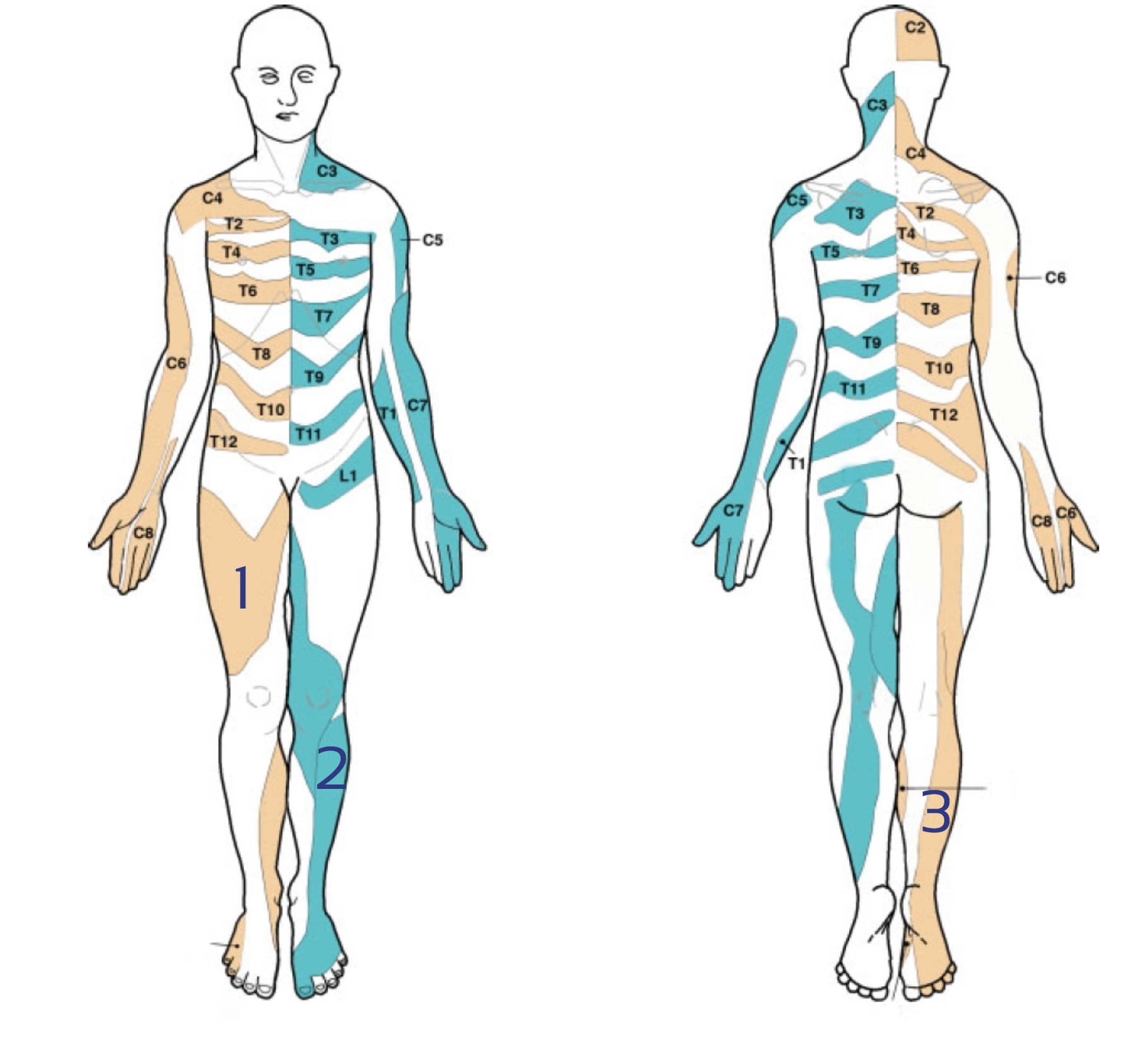

Lee et al. (2008) evaluated the literature and created a composite dermatome map based on published data from 5 papers they considered to be the most experimentally reliable. Their maps look like this:

There is a lot of discussion going on about the reliability of dermatome maps. Check out our blog articles and research reviews if you want to learn more about it:

You can test the lower limb myotomes as explained in the following video:

Be aware, that there can be other underlying reasons for nerve root entrapment than a herniated disk. On top of that, pain radiating to the proximal leg could also be referred pain instead of radicular pain. For more information check out the following videos:

- Lumbar Radicular Pain vs. Referred Pain

- Lumbar Radicular Syndrome vs. Intermittent Neurogenic Claudication from Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

5 ESSENTIAL MOBILIZATION / MANIPULATION TECHNIQUES EVERY PHYSIO SHOULD MASTER

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

As always, treatment should be based on your findings from patient history-taking and examination. The goal is to focus on modifiable negative prognostic factors that can be influenced by therapy. Factors that we can directly influence positively are a high level of pain, disability, range of motion, and decreased joint mobility. Factors that might be influenced directly through advice and education, but also indirectly through treatment, are movement-related fear, catastrophic thinking, and passive coping.

If you go through the list of prognostic factors you can see that there are quite a couple of factors that we will hardly or not be able to influence. If a patient presents with dominant psychosocial factors or work-related factors, Zwart et al. (2021) recommend considering contacting other medical professionals like psychologists or a physiotherapist specialized in work rehabilitation.

What does the evidence say about effective treatments?

It may come as a surprise, but the evidence on the effectiveness of conservative treatment options for lumbosacral radicular syndrome is extremely scarce. Luijsterburg et al. (2008) have found that physiotherapy is not more effective than general care by a GP in terms of pain and disability at 3, 6, 12, and 52 weeks. However, there were indications that physiotherapy was especially effective regarding the global perceived effect in patients reporting severe disability during the initial consultation. Furthermore, a systematic review by Fernandez et al. (2015) found that exercise provides small, superior effects on leg pain in the short term compared to advice to stay active for patients experiencing sciatica. However, the small effect disappeared in the long term. Albert et al. (2012) compared symptom-guided exercises, information, and advice to stay active with sham exercises with information and advice to stay active. They found that the intervention group had clinically significant superior outcomes after 4.8 treatment compared to the sham group in terms of global assessment, functional status, pain, vocational status, and clinical finding.

Paatelma et al. (2008) compared orthopedic manual therapy, the McKenzie, and advice to stay active in patients with low back pain. While all three groups equally improved at 3 months, the McKenzie group performed significantly better than the “stay active” group in terms of back, leg pain, and disability at 6 months and 1 year. There was no difference between manual therapy and the McKenzie method.

Ye et al. (2015) compared lumbar spine stabilization exercises with general exercise in patients with lumbar disc herniations. Both groups showed a significant reduction in pain and disability scores at 3 and 12 months post-exercise compared with before treatment. The stabilization group showed a significant reduction in the average score of the pain for low back pain and disability at 12 months post-exercise compared with the general exercise group. Unfortunately, the authors did not use a third control group to compare the effects to advise to stay active.

Neto et al. (2017) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of lower body quadrant neural mobilization in healthy and low back pain populations. They found a moderate effect size for neural mobilization on increasing flexibility and large effect sizes for pain and disability reduction in patients with low back pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Basson et al. (2017) focused on the effectiveness of neural mobilization in musculoskeletal conditions with a neuropathic component. They found increased pain and decreased disability in patients with chronic low back pain. Patients with lumbosacral radicular syndrome often report provocation of symptoms with flexion. For this reason, we recommend to start with neurodynamic techniques with the SLR slider, followed by the SLR tensioner. As soon as the patient’s leg pain is reduced or close to absent and he or she can tolerate flexion, the Slump technique can be used, again starting with the slider, followed by the tensioner technique.

After the acute phase, patients often experience persistent back pain, but no more leg pain. This is often a result of learned protective behavior (such as avoiding flexion and co-contraction of the lumbar muscles) that was initially helpful, but that can be detrimental in the long term. Next to extensive re-assurance and explanation, the following exercises can be helpful to challenge the patient’s fear-avoidance behavior and to re-establish confidence in their backs:

So a herniated disc and sciatica do not necessarily mean that one needs to get surgery. In the Netherlands, about 5-15% of patients with lumbosacral radicular syndrome end up getting surgery. But how effective is surgery? A systematic review by Jacobs et al. (2011) showed that conservative treatment and surgery are equally effective after 1 and 2 years. The only advantage that surgery might offer is faster pain relief for patients with 6-12 weeks of radicular pain. Clark et al. (2019) performed another more recent systematic review and reached the same conclusion: “Compared with nonsurgical interventions, surgery probably reduces pain and improves function in the short- and medium term, but this difference does not persist in the long-term”. However, other options for pain relief should be considered first such as NSAIDs, weak opioids, or epidural injections, like the NICE guidelines from the UK suggest.

While surgery or just time usually improves a patient’s leg pain, a lot of patients we see fail to improve their back pain. In these cases, the main role for us as clinicians probably is that of providing education and reassurance and helping patients to regain confidence in their backs. This can be done with a graded activity or graded exposure program (see video above) to challenge specific movement-related fears such as bending over.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Finally! How to Master Treating Spinal Conditions in Just 40 Hours Without Spending Years of Your Life and Thousands of Euros - Guaranteed!

What customers have to say about this course

- Shachaf Alexander19/07/24Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the spine

Interesting course packed with useful data and practical tools.

I highly recommend.Verena Fric25/11/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine GREAT COURSE ABOUT THE SPINE

great course, best overview about the different syndromes of the spine, very helpful and relevant for the work with patients - Peter Walsh01/09/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine 5 starsChristoph21/12/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Really a well done course, using the modern ways of teaching. Compliments! Sometimes for me you entered too much into details instead of touching more important chapters of Spine treatment like techniques for the treatment of muscles and fascias

- John09/10/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine EXCELLENT COURSE HIGHLY RECOMMEND

As a newly graduated physiotherapist i highly recommend this course just to know you are on the right track with your patients. the information presented is very clear and easy to follow as well as the great physiotherapy style videos. It makes learning actually fun , thanks guys for all your hard work. Well deserved.Alexander Bender06/09/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine During the corona crisis, I booked many online courses and webinars, but none were as entertaining and well thought out as PhysioTutors’ courses.

All units are well summarized, meaningfully broken down and easy to understand.

I am looking forward to the other courses.

Many greetings from Germany. - GHADEER05/01/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine VERY INFORMATIVE AND UPDATED

for anyone who is lost in handling spine cases, this course is very helpful.MICHAEL PROESMANS20/12/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine HIGHLY METHODICAL, WITH PLENTY OF SCIENTIFIC REFERENCE

Clear, structured and well researched course concerning most common pathologies of the spinal complex.

Plenty of informative modules, with detailed video-analysis.

If you’re looking for a course to study in your own time, with enough depth and scientific background, then you’ve found a very good one here.

Bang for buck, a great course. - BENOIT08/05/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine After finishing the Orthopedic course for Lower & Upper limbs, I was looking forward to begin this Spine specific course.

Really good overview about all spine pathologies from epidemiology to diagnosis & treatment which made me more confident to care for my future patients.

ANOTHER GREAT COURSE !

The courses are well detailed with lot of informations and videos.

For me these 2 courses are must to see to learn and update knowledge for most common pathologies in Physiotherapy.Nicolas Cardon27/04/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine This is a very interesting course !

We can find many informations about the main pathologies and their differential diagnosis and about objective and subjective exam. Videos are clear and well designed.

It’s a very well course for these who wish complete their Orthopedic Manual Therapy curriculum.

A French Physio’