Low back pain, an overview of prevention and active treatment options

Introduction

Low back pain is a major cause of disability worldwide. Although most low back pain episodes have a good prognosis, where in the first 6 to 12 weeks important improvements can be expected, the recurrent character can be quite frustrating for patients. As low back pain can recur, patients often think their back is weak or vulnerable and may often avoid certain activities to evade what they think exposes them to a risk of another episode. This way they adopt some maladaptive coping strategies which may predispose them to recurrent episodes.

Secondary prevention

Can low back pain be prevented in a population that has had a previous episode? In 2016, a systematic review by Steffens et al. found exercise, when combined with education, effective in reducing the risk of a future episode of low back pain with a relative risk of 0.55 (95% CI 0.41-0.73). Other interventions were ineffective or lacked evidence. Importantly, they included individuals who did not have low back pain at the time of inclusion in the study. But as was mentioned previously, the recurrent character of the condition makes it important to study how the transition from acute low back pain to chronic conditions can be prevented.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by de Campos et al. (2020) it was investigated whether preventive strategies exist to reduce the future impact of low back pain. They concluded by moderate quality evidence that exercise was able to prevent future low back pain intensity (MD −4.50; 95% CI −7.26 to −1.74) in the short term. When exercise was combined with education, interestingly no preventive effects were found in the short term and long term for low back pain intensity and neither for disability in the short term. However, moderate quality evidence found education and exercise effective in reducing future disability (MD −6.28; 95% CI −9.51 to −3.06). Education alone was not effective in preventing future disability and pain intensity in the short and long term follow-up.

Moderate-quality evidence based on three trials (612 participants) indicates that exercise alone can reduce future LBP intensity (MD -4.50; 95% CI -7.26 to -1.74) at short-term follow-up.

Treatment of LBP: effectiveness of aerobic activities like walking/running

You are probably familiar with the advice to stay active despite being in a low back pain episode. But can regular physical activity like walking, running, cycling or swimming help in the recovery from low back pain? Pocovi et al. (2021) investigated this and found that alternate interventions like stabilization exercises, physiotherapy, and general exercise were more effective in reducing pain intensity in the short term (SMD 0.81; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.34; I2 91%) and in the medium term (SMD 0.80; 95% CI 0.10 to 1.49; I2 94%) compared to running or walking. These effects lead to reductions of approximately 14 points on a 0-100 numeric pain rating scale. Both were based on low-certainty evidence.

Considering disability, similar effects were seen in favor of the alternate interventions. In the short term, high-certainty evidence found a small effect (SMD 0.22; 95% CI 0.06 to 0.38; I2 0%) corresponding to a decrease of 3.8 points on the 0-100 Oswestry Disability scale. Quite similar, in the medium term a small effect (SMD 0.28; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.51; I2 25%) leading to a reduction of 4.1 points in favour of the alternate interventions were observed.

Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine

Become confident in screening, assessing & treating the most common pathologies in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine based on the very latest evidence from 440 research articles.

So what will you answer your patient if they ask your opinion about these aerobic exercises? Okay, the effects appear to be small but nevertheless they may be an important step into activating the patient and preventing them from avoiding activities. The investigation also compared the effectiveness of these aerobic exercise modes to no or minimal interventions for low back pain and there high-certainty evidence concluded that exercise was more effective than minimal or no treatment for low back pain in the short term with a small effect size (SMD -0.23; 95% CI -0.35 to -0.10; I2 0%) equivalent to a reduction of 4.4 points on the 0-100 pain rating scale. These effects were sustained in the medium term (SMD 0.26; 95% CI -0.40 to -0.13; I2 0%) equivalent to an estimated mean difference of 5.7 points on the 0-100 pain rating scale. The same findings were observed for disability in the short term where walking and running were more effective for reducing disability than no or minimal interventions with a mean difference (SMD 0.26; 95% CI -0.40 to -0.13; I2 0%) corresponding to 2.3 points of change on the 0-100 Oswestry Disability Scale.

It seems that, considering the small differences between walking or running and alternate interventions, we can advise both to what matches the preferences and possibilities of the patient in front of you. When we look at one study in particular that was included in this meta-analysis (Shnayderman et al., 2013), both strength training and walking were effective in reducing symptoms, disability and fear-avoidance and in increasing walking distance and muscle endurance. Quite obvious, the strength training group achieved higher improvements in muscle endurance and the walking interventions increased walking distance to a higher extent, but the differences between the walking and strength training groups were not significant and both led to positive improvements.

What about low back pain in athletes?

Similarities to the above mentioned studies are seen when looking at athletes in particular. The systematic review with meta-analysis of Thornton et al. in 2021 found all exercise approaches effective at reducing pain and improving function in athletes with low back pain. Also here, any type of exercise appears to be better than rest, and targeted, dynamic, functional (sport-specific) exercise may be the most beneficial in this specific group of patients. There was insufficient evidence to support manual therapy (massage and spinal manipulation) as stand-alone interventions for managing low back pain in athletes.

What about invasive treatment options?

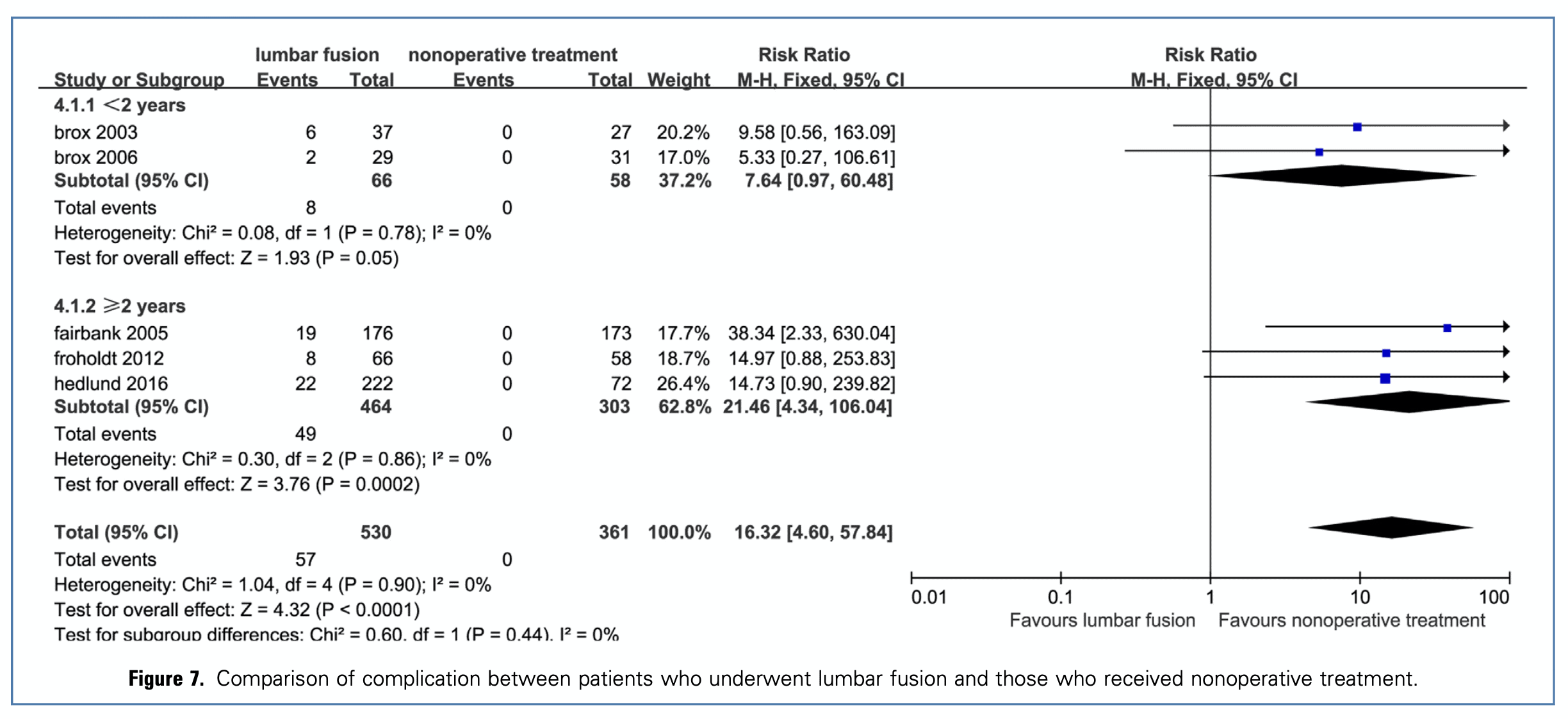

When working with people experiencing low back pain you may get the question if surgery could help them out. Maybe they’ve heard from someone that surgery might cure their back pain. Lumbar fusion is one of the most commonly performed procedures for degenerative disc disease in the lumbar spine. The meta-analysis by Xu et al. (2020) concluded that fusion surgery in patients with degenerative disc disease was no better than nonoperative treatment in terms of pain and disability at either short or long term follow-up. Also, considering the possible complications that may arise and the lax criteria used to enroll patients into RCTs, it seems safer to recommend fusion only in very strictly selected patients.

Key take home messages

- Low to high-certainty evidence indicates that walking/running was less effective than alternate treatments in reducing pain and disability, but these differences were relatively small.

- When walking/running was compared to minimal or no intervention, high-certainty evidence found that walking/running was slightly more effective for reducing pain across all time points, and disability in the short term.

- Choose the type of intervention based on the patients’ preferences and possibilities. Remember that being active and engaging in physical activity is better than doing nothing independent of the type of activity chosen!

References

Shnayderman I, Katz-Leurer M. An aerobic walking programme versus muscle strengthening programme for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013 Mar;27(3):207-14. doi: 10.1177/0269215512453353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22850802/

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin CC, Chenot JF, van Tulder M, Koes BW. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018 Nov;27(11):2791-2803. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2.pdf

Verhagen AP, Downie A, Popal N, Maher C, Koes BW. Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review. Eur Spine J. 2016 Sep;25(9):2788-802. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4684-0. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27376890/

Xu W, Ran B, Luo W, Li Z, Gu R. Is Lumbar Fusion Necessary for Chronic Low Back Pain Associated with Degenerative Disk Disease? A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021 Feb;146:298-306. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.121. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33253955/

Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017 Feb 18;389(10070):736-747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27745712/

de Campos TF, Maher CG, Fuller JT, Steffens D, Attwell S, Hancock MJ. Prevention strategies to reduce future impact of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2021 May;55(9):468-476. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101436. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32646887/

Thornton JS, Caneiro JP, Hartvigsen J, Ardern CL, Vinther A, Wilkie K, Trease L, Ackerman KE, Dane K, McDonnell SJ, Mockler D, Gissane C, Wilson F. Treating low back pain in athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Jun;55(12):656-662. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102723. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33355180/

Steffens D, Maher CG, Pereira LS, Stevens ML, Oliveira VC, Chapple M, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Hancock MJ. Prevention of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Feb;176(2):199-208. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26752509/

Pocovi NC, de Campos TF, Lin CC, Merom D, Tiedemann A, Hancock MJ. Walking, Cycling, and Swimming for Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Nov 16:1-64. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2022.10612. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34783263/

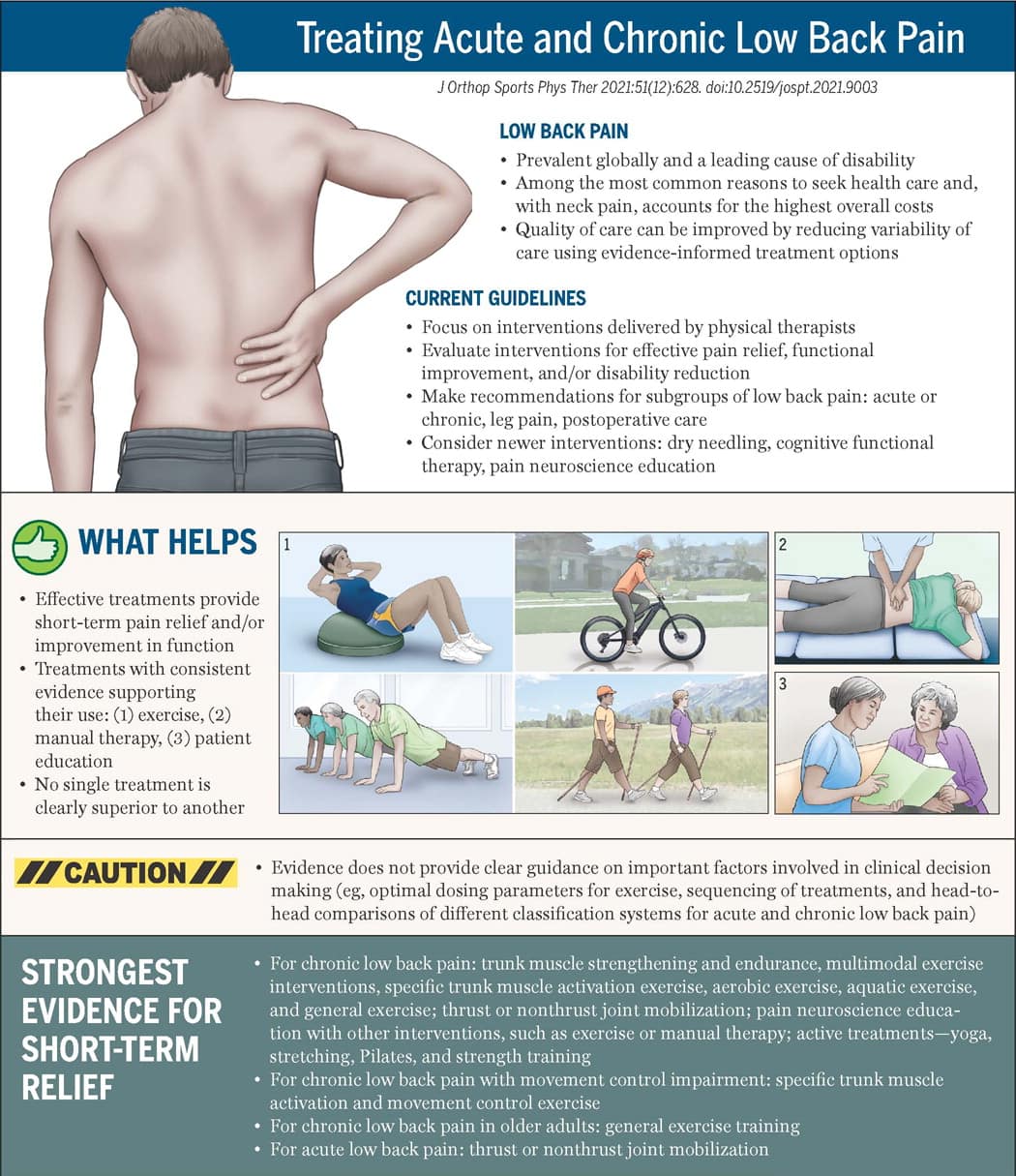

Infographic based on clinical practice guidelines by George et al titled “Interventions for the Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021” (J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(11):CPG1-CPG60. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2021.0304). Illustrations by Jeanne Robertson.

Ellen Vandyck

Research Manager

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.