Lifting with a flexed lumbar spine – Safe and possibly even beneficial?

Whether it be in the classroom, clinic, at work, or in the gym, for decades people have argued that lifting with a flexed spine is inherently bad for the health of someone’s back. You’ve seen the pictograms (see below) and models showing what’s supposed to be the safest and best way to lift an object but is that really the case?

In this blog, we want to take a look at recent research examining this topic.

Prefer watching instead of reading? Then check out our video here:

Spinal flexion in animal models

Most of the research that is used as the argument against lifting with a flexed spine comes from animal models that showed a higher potential of injury and “degeneration” when loading a spinal segment in a flexed versus neutral position (Wade et al. 2014, Wade et al. 2017, Berger-Roscher et al. 2017). We can argue that these observations don’t translate to a living and breathing human being whose tissues are able to adapt to loads they are exposed to. Also, as discussed in another blog article, lumbar disc degeneration is an inevitable and normal process of aging and the correlation to pain is poor.

Lifting with a flexed lumbar spine – unavoidable?

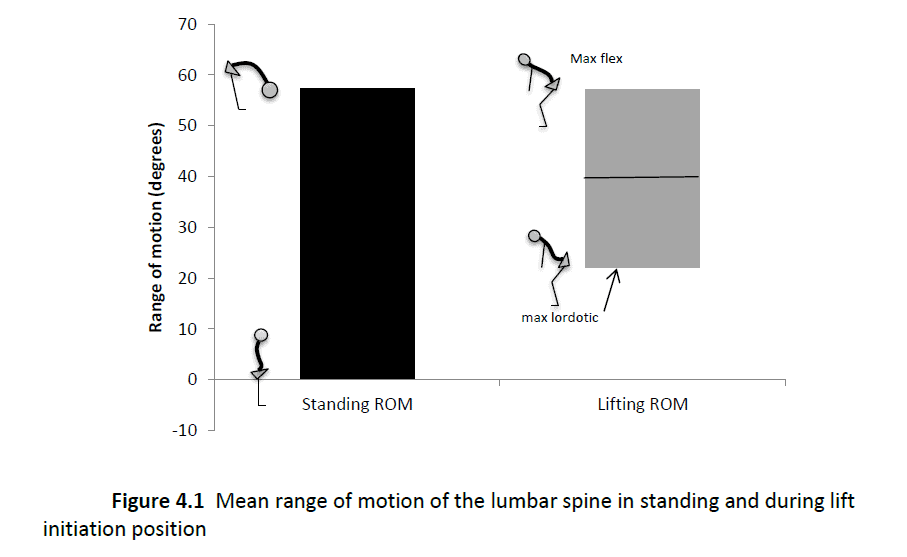

More than 20° of lumbar flexion occurs in movements with a straight or neutral spine

Secondly, while the backs in all those pictograms may appear to be straight, research has actually demonstrated that even when we try to perform lifts such as a Deadlift or Good Mornings with seemingly neutral spines, there is a substantial amount of flexion. More than 20° of flexion actually (Holder 2013, Vigotsky et al. 2015)

When we compare that to spinal flexion ranges from in-vitro models that were labeled as injurious (around 15-18°) then it seems impossible to avoid risking a back injury despite our best efforts to stay neutral during lifting.

Lifting with a flexed spine – is it beneficial?

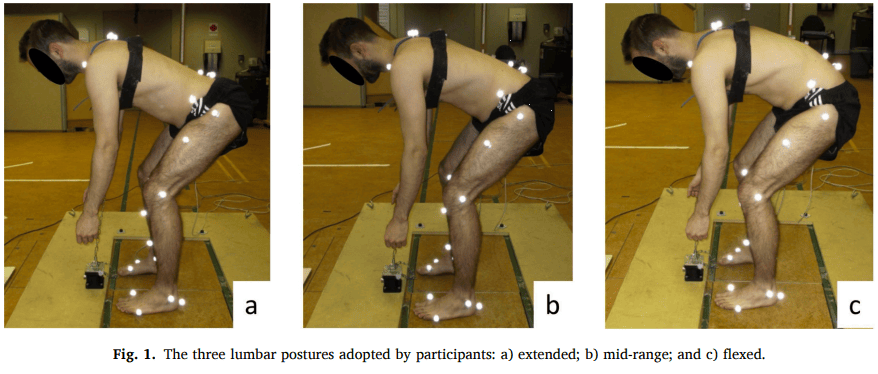

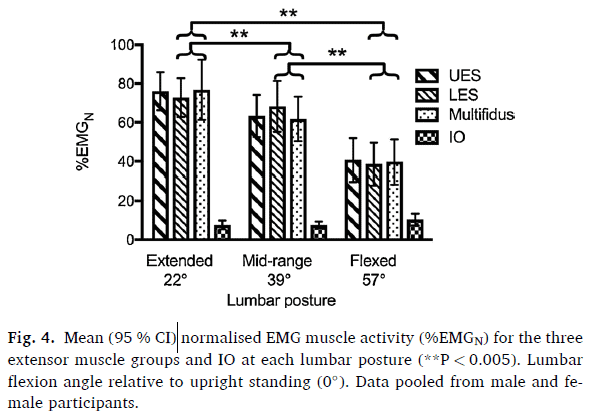

Recently, Mawston et al. (2021) wondered how differences in lumbar spine postures influence trunk extensor strength, muscle activity, and neuromuscular efficiency during maximal lifting. In their study, they assessed 26 young healthy pain-free subjects. Their task was to generate maximal isometric force from a lifting position in three lumbar postures: extended, mid-range, and flexed as seen in the pictures here.

What they found was that lifting with a flexed lumbar spine resulted in significantly higher trunk extensor muscle moments as well as lower surface EMG activity compared to the extended and mid-range spine postures. Overall, the neuromuscular efficiency was highest in the flexed position, which according to the authors further questions why we are advocating so much against lifting with a flexed spine.

However, Greg Lehman posted valid criticism about those conclusions on Twitter as comparing measured EMG amplitude across different muscle positions is flawed as this heavily influences EMG accuracy, especially as all trials required maximal effort by the participants, which you’d expect to result in maximal EMG readings.

Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine

Master Treating the Most Common Spinal Conditions in Just 40 Hours

Mawston and colleagues reason that lifting with a flexed spine improves the length-tension relationship of the erector spinae and benefits from the elasticity of passive structures such as the posterior longitudinal ligament. Increased load on passive structures is often mentioned as an argument against lifting with a flexed lumbar spine as it may result in increased shearing forces and tissue creep. However, the authors reason that judging from the relatively small difference in EMG activity of the upper and lower erector spinae, the reliance on passive structures and risk of shear is most likely minimal.

So does this study add to the evidence that lifting with a flexed spine should not be discouraged and avoided at all costs? Yes, we admit the subjects in the study were young, healthy, and pain-free, and lumbar flexion is often painful in patients with low back pain. But avoiding flexion entirely is thus A) anatomically not possible and B) apparently not efficient either. If spinal flexion hurts then we can modify those symptoms by temporarily moving differently and as always we should gradually build up our tolerance to any repetitive movement giving our body and tissues time to adapt. If you want to get some ideas on how you can reintroduce spinal flexion in patients hesitant to move into flexion, check out the following video

Also, the way we move differs between individuals and is only one piece of the pain puzzle.

Alright, thanks a lot for reading!

Andreas

References

Andreas Heck

CEO & Co-Founder of Physiotutors

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.