Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CMS) | Diagnosis & Treatment

Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CMS) | Diagnosis & Treatment

Introduction & Epidemiology

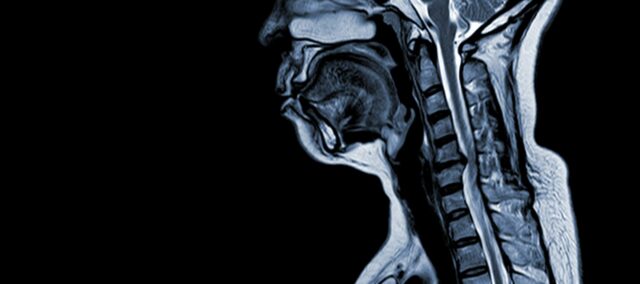

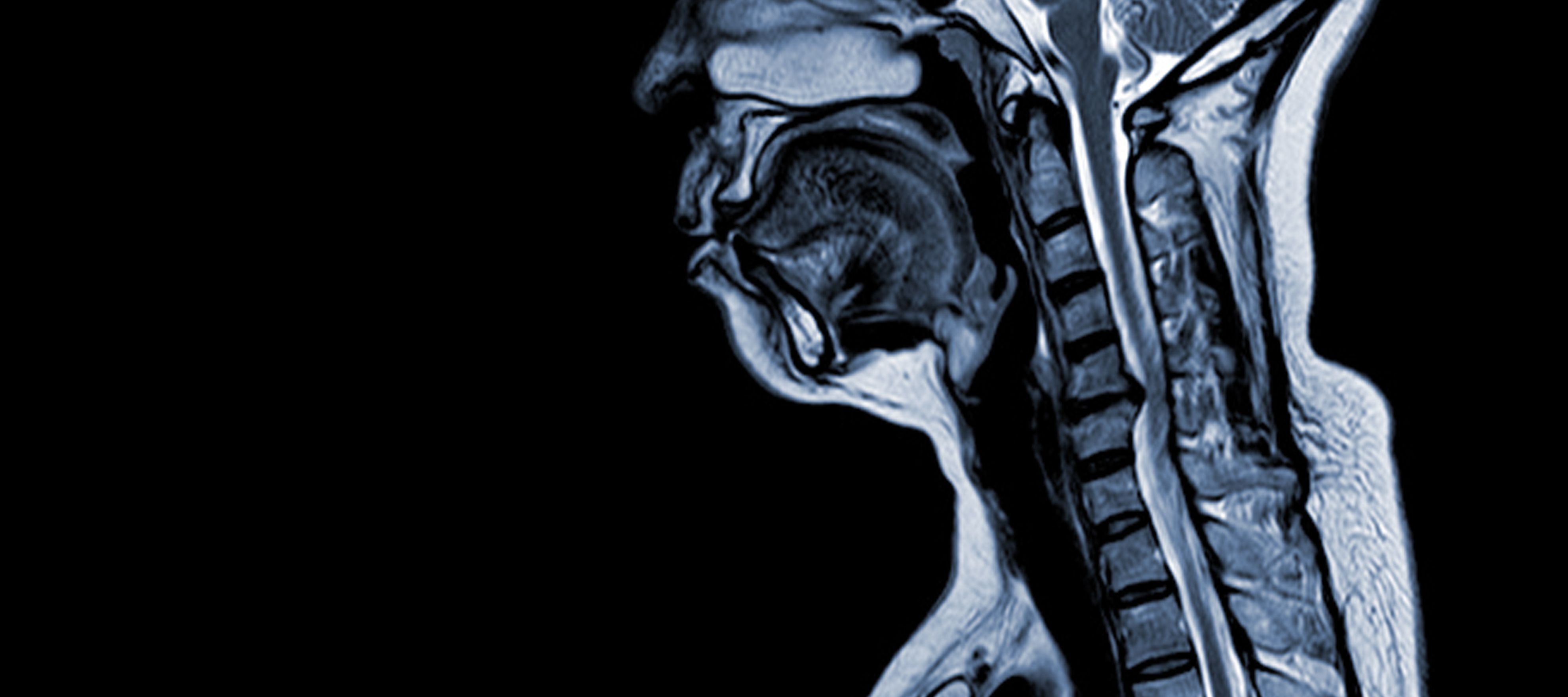

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a neurological condition that is the leading cause of spinal cord injury in adults. In simple terms, it involves the compression or damage of the spinal cord in the neck, primarily due to the natural aging process that affects the cervical vertebrae. The term ‘myelopathy’ stems from the Greek words ‘myelon,’ which means ‘spinal cord’ and ‘pathos,’ signifying ‘disease’.

Epidemiological studies have provided valuable insights into CSM. Northover et al. (2012) conducted an observational study involving 41 patients, and their findings revealed a male-to-female ratio of 2.7:1, with the average age at diagnosis being 63.8 years. It was observed that CSM typically affects multiple segments of the cervical spine, with the C5/C6 level being the most commonly affected.

Additionally, Aizawa et al. (2016) conducted a study on spinal surgeries performed between 1998 and 2012. They found that 19.8% of these surgeries were related to cervical myelopathy, highlighting the prevalence of this condition in the broader context of spinal health. Other spinal issues, such as lumbar spinal canal stenosis (35.9%) and lumbar disc herniation (27.7%), also featured prominently in their research.

CSM is a complex medical condition with a multifactorial pathophysiology that includes structural changes in the cervical spine. Several key factors contribute to its development and progression:

Risk Factors:

- Trauma: Traumatic events, such as accidents or injuries, can accelerate the degeneration of cervical spinal discs and increase the risk of CSM.

- Axial Weight Bearing on Neck/Head: Activities that involve bearing excessive axial weight on the neck or head can lead to increased mechanical stress on the cervical spine, exacerbating disc degeneration and other structural changes.

- Genetic Predisposition of Vertebrae: Some individuals may have a genetic disposition that makes their cervical vertebrae more susceptible to degenerative changes, which can contribute to CSM.

- Smoking: Smoking is known to have detrimental effects on vascular health and tissue oxygenation, which may exacerbate the progression of CSM and its associated symptoms.

Pathophysiology

- Disc Degeneration (Bulging Disc): CSM often begins with the degeneration of intervertebral discs in the cervical spine, causing them to bulge or protrude into the spinal canal.

- Subperiosteal Bone Formation (Ventral to Spinal Canal): In response to increased mechanical stress, the body forms new bone tissue on the front (ventral) side of the spinal canal, potentially narrowing the space for the spinal cord.

- Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament: The posterior longitudinal ligament may undergo ossification, hardening, and calcifying, contributing to spinal canal narrowing.

- Hypertrophy of Ligamentum Flavum: Hypertrophy of the Ligamentum Flavum causes it to thicken and become less flexible, further encroaching on the space within the spinal canal and compressing the spinal cord.

These structural changes collectively lead to the compression and narrowing of the spinal canal, resulting in the hallmark symptoms and complications associated with CSM. Recognizing these risk factors and understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms involved is essential for both prevention and management. Early diagnosis and appropriate interventions are crucial to mitigate the effects of these structural alterations on the spinal cord.

Use the manual therapy app

- Over 150 mobilization and manipulation techniques for the musculoskeletal system

- Fundamental theory and screening tests included

- The perfect app for anyone becoming a MT

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM) is characterized by a variety of clinical signs and symptoms, although there are no specific features that exclusively define the condition. Patients with CSM may experience the following:

1. Abnormalities in Gait: Patients often exhibit changes in their walking pattern, which can include an unsteady gait, stumbling, and difficulty maintaining balance.

2. Stiffness in the Cervical Spine: CSM can lead to stiffness and reduced range of motion in the neck, making it challenging for individuals to move their heads comfortably.

3. Sharp Pain in the Arms: Patients may report sharp, shooting pain and discomfort in their arms. These symptoms are often associated with nerve compression in the cervical spine.

4. Motor Dysfunction: Motor problems are common and can manifest as muscle weakness, coordination difficulties, and a decrease in fine motor skills, such as manipulating objects.

5. Changes in Sensation: Sensory alterations are common and may involve tingling, numbness, or a “pins and needles” sensation in the arms and hands.

6. Loss of Strength: Patients may experience a loss of strength in the upper limbs, leading to difficulty with everyday tasks and activities.

7. Reduced Proprioception: Proprioception, which is the sense of body position and movement, may be impaired, making it challenging for individuals to coordinate their movements.

8. Toileting Issues: Some patients may experience difficulties with bladder or bowel control due to the involvement of the spinal cord.

9. L’Hermitte’s Sign: This is a distinctive symptom characterized by an electric shock-like sensation that radiates down the spine and into the limbs when the neck is flexed. It is a classic indicator of cervical cord involvement in CSM.

These diverse signs and symptoms can vary in severity from person to person, making the clinical presentation of CSM unique for each patient. Recognizing these manifestations is crucial for diagnosis and early intervention to prevent further spinal cord damage and improve the patient’s quality of life.

Examination

If CSM is suspected, the therapist can use the following test cluster (Cook et al. 2010) in order to help his decision-making:

Cook et al. (2010) produced a cluster of predictive clinical test findings for a sample of patients using a clinical diagnosis as the reference standard for the condition. The goal of the cluster is to detect the disease in early stages to rule out the condition during screening.

The five tests or patient characteristics included in the rule are the following:

- Gate deviation which shows as abnormally wide-based gait, ataxia, or spastic gate.

- A positive Hoffman’s test or Hoffman’s sign which is characterized by a reflex contraction of the thumb and index finger when flipping the distal part of the middle finger.

- Inverted supinator sign which is elicited by quick tapping near the styloid process of the radius which is the attachment of the brachioradialis tendon and it shows in finger flexion or slight elbow extension.

- Positive Babinski sign which shows as an extension of the big toe and fanning of the other four toes when stroking the lateral aspect of the foot sole from the heel forward towards the great toe.

- Age greater than 45 years.

So if 3+/5 of the five aforementioned characteristics are positive the positive likelihood ratio for a cervical spondylosis myelopathy is at 30.9. If only one is positive though the negative likely ratio is at 0.18

MASSIVELY IMPROVE YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LOW BACK PAIN FOR FREE

Use the manual therapy app

- Over 150 mobilization and manipulation techniques for the musculoskeletal system

- Fundamental theory and screening tests included

- The perfect app for anyone becoming a MT

Treatment

Once a diagnosis of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM) is confirmed, the primary decision to be addressed is whether to pursue operative or nonoperative management. CSM is typically regarded as a surgical condition, as studies have shown that nonoperative treatments result in significant impairments in daily life activities over time. Specifically, at the end of one year, nonoperative treatment leads to a 6% rate of impairment, which increases to 21% at two years, 28% at three years, and a substantial 56% at the ten-year mark. (Fehlings et al. 2017)

To date, there is a lack of high-level studies directly comparing the outcomes of operative versus nonoperative management in cases of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM). Nonetheless, significant insights have been gained from various research efforts. Sampath et al. (2000) conducted a prospective, multicenter, nonrandomized trial aimed at comparing surgical and nonoperative treatments for CSM. Their findings indicated that surgical patients tend to experience better outcomes, encompassing functional status, overall pain, and relief from neurologic symptoms, despite a higher burden of disease before the operation.

In 2013, Rhee et al. published a systematic review on CSM management, recommending against nonoperative treatment as the primary approach for patients with moderate-to-severe myelopathy. They suggested that individuals with mild myelopathy might initially opt for nonoperative management but should be closely monitored for any signs of deterioration.

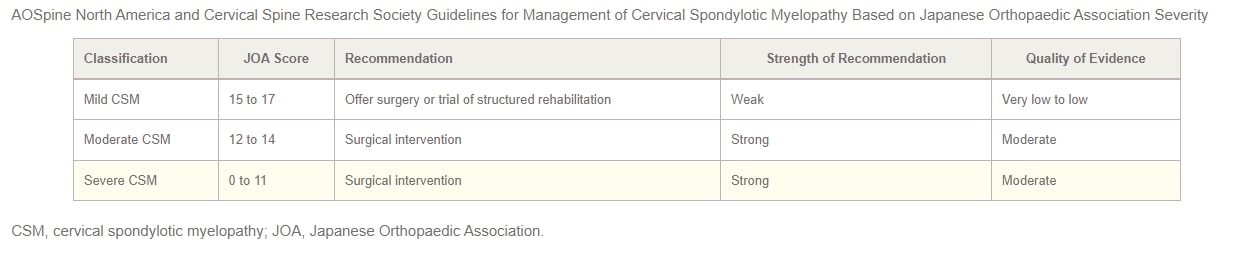

In 2017, AOSpine North America and the Cervical Spine Research Society (CSRS) jointly released guidelines for CSM management based on its severity. For patients with mild CSM, the options of surgical intervention or a supervised trial of structured rehabilitation should be presented. If nonoperative management does not yield improvement or the patient’s condition worsens, surgical intervention is recommended. In cases of moderate-to-severe CSM, the guidelines strongly advocate for surgical intervention. Patients with cervical cord compression but lacking clear signs of myelopathy or root compression should receive counseling on the risks of disease progression, education about symptoms to watch for, and regular clinical follow-up.

Finally, for patients exhibiting cervical cord compression along with evidence of radiculopathy, the authors propose considering either surgical treatment or structured rehabilitation with close follow-up. The 2017 practice guidelines for CSM management, stratified by severity, are summarized in the table below:

Do you want to learn more about the cervical area and cervical radiculopathy in particular? Then check out our blog articles and research reviews:

- Determining the Level of Cervical Radiculopathy

- Why Dermatome Maps may still useful

- 3 Truths University Didn’t Tell You about Radicular Syndrome

- Physiotherapy for Painful Radiculopathies

References

Use the manual therapy app

- Over 150 mobilization and manipulation techniques for the musculoskeletal system

- Fundamental theory and screening tests included

- The perfect app for anyone becoming a MT

Finally! How to Master Treating Spinal Conditions in Just 40 Hours Without Spending Years of Your Life and Thousands of Euros - Guaranteed!

What customers have to say about this course

- Shachaf Alexander19/07/24Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the spine

Interesting course packed with useful data and practical tools.

I highly recommend.Verena Fric25/11/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine GREAT COURSE ABOUT THE SPINE

great course, best overview about the different syndromes of the spine, very helpful and relevant for the work with patients - Peter Walsh01/09/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine 5 starsChristoph21/12/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Really a well done course, using the modern ways of teaching. Compliments! Sometimes for me you entered too much into details instead of touching more important chapters of Spine treatment like techniques for the treatment of muscles and fascias

- John09/10/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine EXCELLENT COURSE HIGHLY RECOMMEND

As a newly graduated physiotherapist i highly recommend this course just to know you are on the right track with your patients. the information presented is very clear and easy to follow as well as the great physiotherapy style videos. It makes learning actually fun , thanks guys for all your hard work. Well deserved.Alexander Bender06/09/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine During the corona crisis, I booked many online courses and webinars, but none were as entertaining and well thought out as PhysioTutors’ courses.

All units are well summarized, meaningfully broken down and easy to understand.

I am looking forward to the other courses.

Many greetings from Germany. - GHADEER05/01/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine VERY INFORMATIVE AND UPDATED

for anyone who is lost in handling spine cases, this course is very helpful.MICHAEL PROESMANS20/12/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine HIGHLY METHODICAL, WITH PLENTY OF SCIENTIFIC REFERENCE

Clear, structured and well researched course concerning most common pathologies of the spinal complex.

Plenty of informative modules, with detailed video-analysis.

If you’re looking for a course to study in your own time, with enough depth and scientific background, then you’ve found a very good one here.

Bang for buck, a great course. - BENOIT08/05/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine After finishing the Orthopedic course for Lower & Upper limbs, I was looking forward to begin this Spine specific course.

Really good overview about all spine pathologies from epidemiology to diagnosis & treatment which made me more confident to care for my future patients.

ANOTHER GREAT COURSE !

The courses are well detailed with lot of informations and videos.

For me these 2 courses are must to see to learn and update knowledge for most common pathologies in Physiotherapy.Nicolas Cardon27/04/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine This is a very interesting course !

We can find many informations about the main pathologies and their differential diagnosis and about objective and subjective exam. Videos are clear and well designed.

It’s a very well course for these who wish complete their Orthopedic Manual Therapy curriculum.

A French Physio’