The Presence of Cervical Impairments in RCRSP Patients versus Healthy Controls

Introduction

In rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP), the pain is typically described over the deltoid region and the upper arm when the arm is moved. Although neck pain is not a cardinal symptom, the authors of this study examined the presence of cervical impairments in RCRSP patients, as they hypothesized that inadequate cervicothoracic mobility may be a risk factor for developing shoulder pain and that improper activation of neck muscles can negatively influence upper limb tasks. As previous studies looking at these risk factors were inconclusive, this study was carried out with attention to the key limitations (small sample sizes, confounding factors, etc.) of earlier studies in mind.

Methods

This study investigated the relationship between the cervical spine and rotator cuff-related shoulder pain. The authors aimed to clarify how neck mobility, pain sensitivity, and strength differ between individuals with RCRSP and asymptomatic controls. It also explores the associations between neck active range of motion (AROM) and shoulder outcomes.

Therefore, a cross-sectional study was conducted with 50 patients diagnosed with RCRSP, who were compared against 50 asymptomatic controls. The comparison was made to determine if cervical impairments in RCRSP exist.

Individuals aged 18-65 years with unilateral shoulder pain lasting at least three months were included in the RCRSP group. They had to report pain during resisted shoulder abduction or external rotation of at least 3 points on VAS and no pain at rest. Further, they had to report provocation of their familiar pain on at least three of the following tests:

Exclusion criteria included neck pain within the last three months or recurrent neck pain, history of shoulder surgery, signs of radiculopathy, positive Spurling or Arm Squeeze Test, systemic disease, traumatic shoulder pain, limited passive shoulder external rotation ROM (<45° or <50% compared to contralateral), signs of instability (positive sulcus sign or positive drawer or apprehension test), or current pain medication use.

The asymptomatic controls were individuals aged 18-65 years who had no symptoms of shoulder or neck pain in the last three months. They had no neurological dysfunction of the upper limb, they were not on current pain medication, and had no previous history of shoulder surgery.

Sociodemographic variables were obtained, including sex, age, height, and weight. Kinesiophobia was measured using the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11), and catastrophizing levels were recorded with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS).

The shoulder outcomes of interest were pain intensity, which was measured using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain during the last week and current pain intensity, and shoulder disability, which was assessed using the Spanish-validated Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), scoring from 0 (no disability) to 100 (maximum disability).

The following neck outcomes were captured in a randomized order:

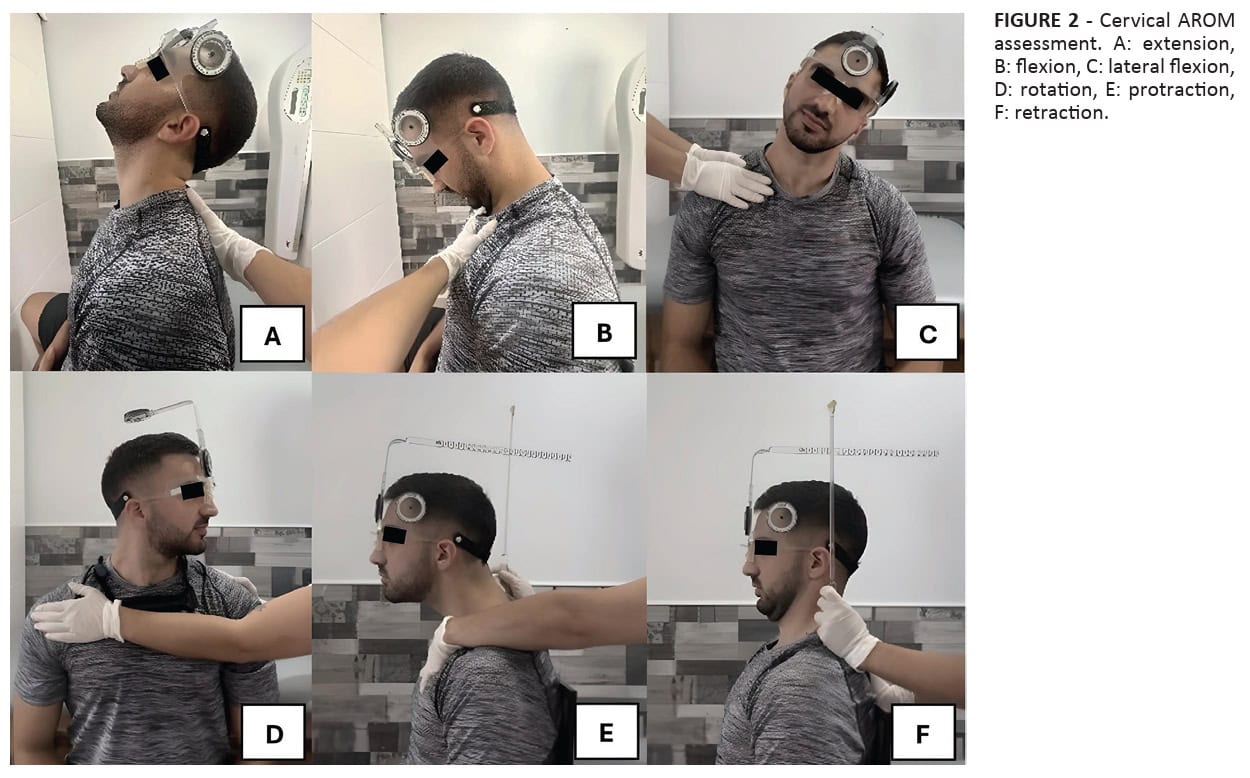

Neck active range of motion (AROM): Measured with a CROM device for flexion, extension, lateral flexion, rotation, protraction, and retraction. Three measurements were taken and averaged for each movement.

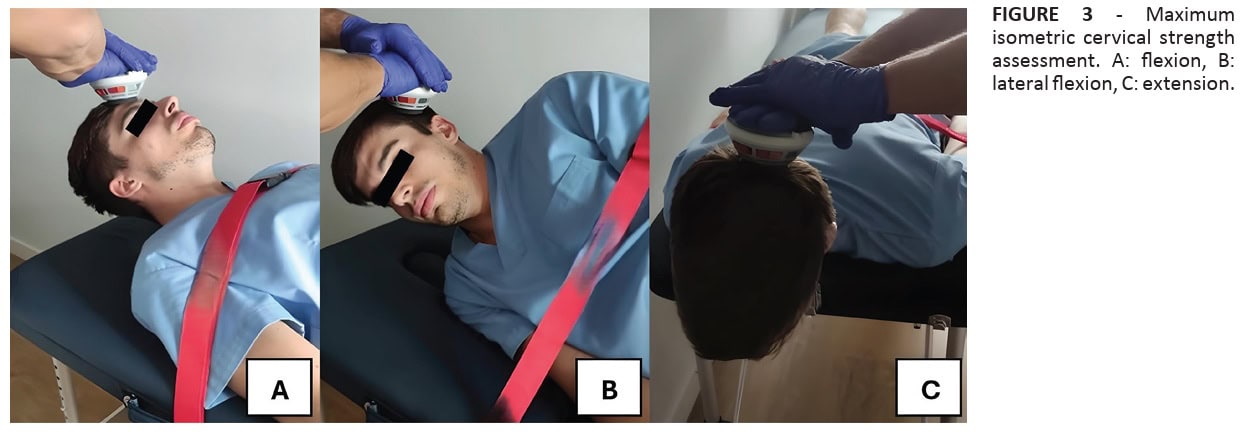

Maximal isometric neck strength: Measured using a handheld dynamometer for neck flexion, extension, and lateral flexion. Participants performed three 5-second maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVICs) with 30 seconds of rest in between repetitions, and the average was used for analysis.

Neck Pressure Pain Thresholds (PPTs): Assessed with a digital algometer with a 1 cm² probe. Measurements were taken bilaterally on the C5-C6 zygapophyseal joints. Three consecutive measurements were obtained with a 30-second rest period.

Results

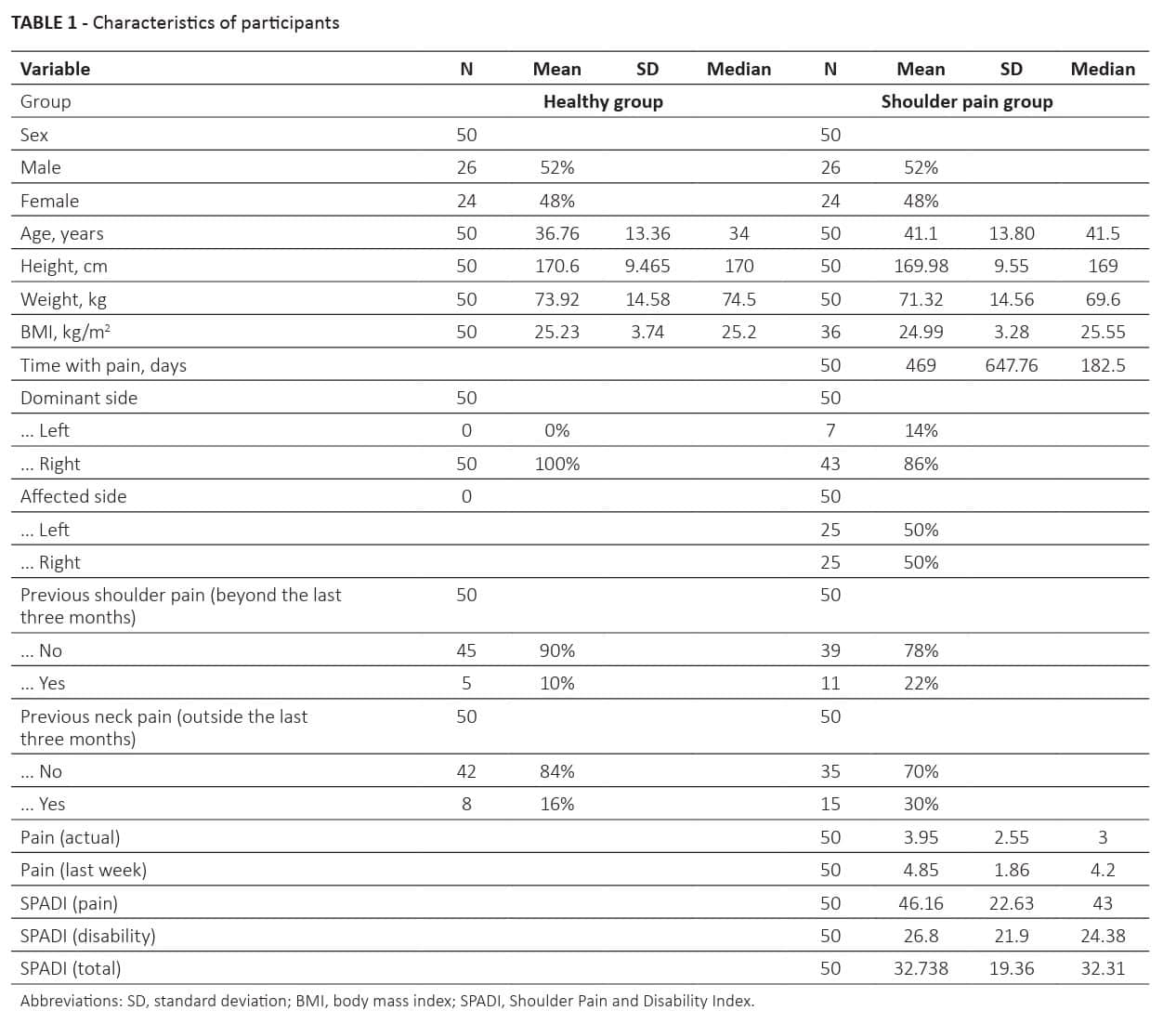

A total sample of 100 participants was included, with equal representation across the groups: 50 were asymptomatic controls, and 50 were patients with RCRSP. The mean age in the RCRSP group was 41.1 years (SD: 13.8), and the healthy controls were on average 36.76 years (SD: 13.36).

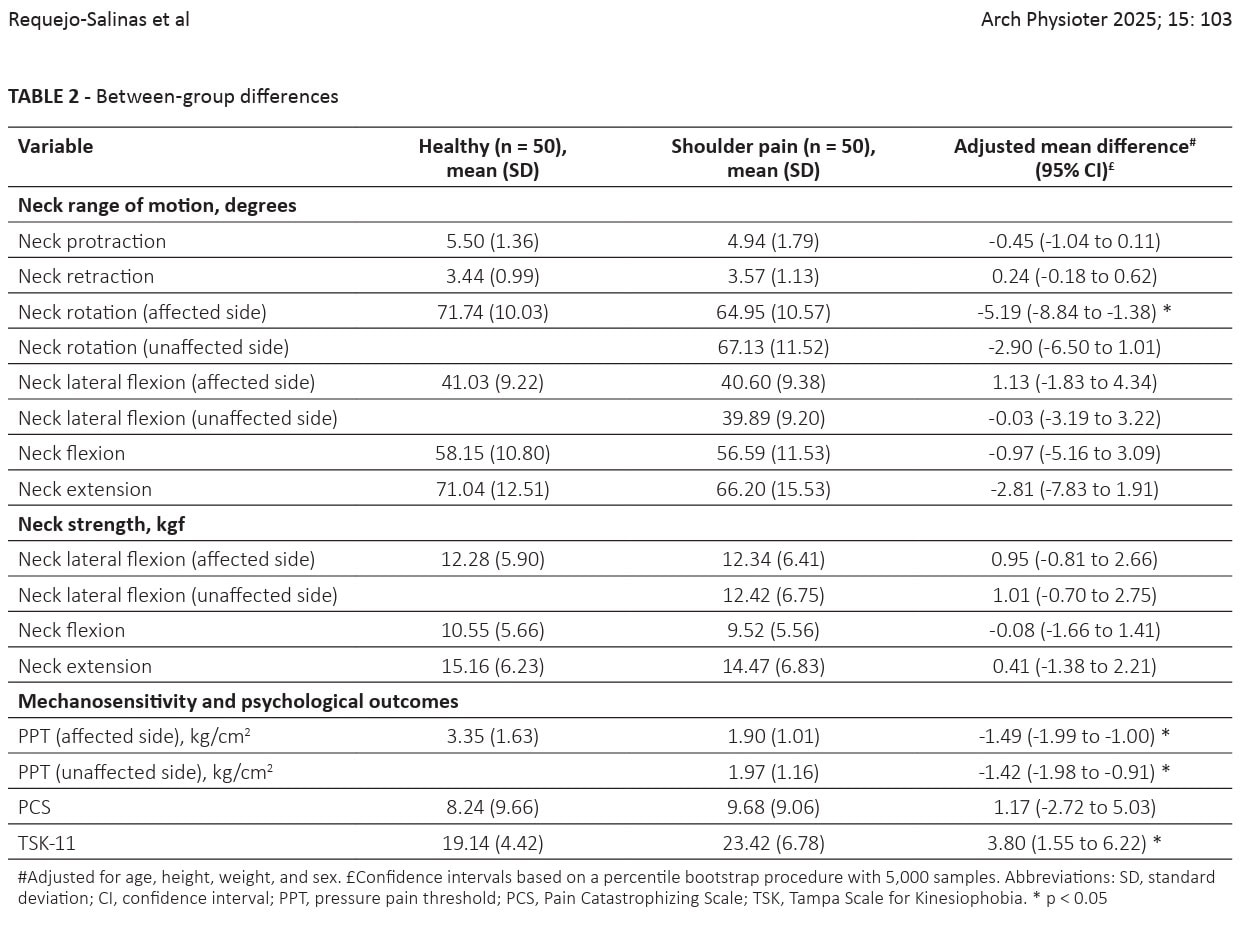

Between-group Differences in Neck AROM: The RCRSP group showed significantly reduced neck rotation towards the affected shoulder (mean difference: -5.19°; 95% CI: -8.84 to -1.38°) compared to asymptomatic controls. No significant differences were found in other neck AROM measures. This means that the study found cervical impairments in RCRSP patients for the active rotation range of motion towards the painful shoulder.

Between-group Differences in Neck Muscle Strength: No significant adjusted mean between-group differences were found in neck muscle strength.

Between-group Differences in Neck PPTs: The RCRSP group exhibited greater pain sensitivity, as objectified by lower neck PPTs, bilaterally:

- Affected side: -1.49 kg/cm² (95% CI: -1.99 to -1.00)

- Unaffected side: -1.42 kg/cm² (95% CI: -1.98 to -0.91)

Psychological outcomes

No between-group differences were observed regarding the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), but the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) revealed a significant difference between the RCRSP patients and healthy controls. Healthy controls had a mean TSK-11 score of 19.14 (SD: 4.42), whereas the RCRSP group scored 23.42 (SD: 6.78). This led to a significant between-group difference of 3.80 (95% CI: 1.55 to 6.22)

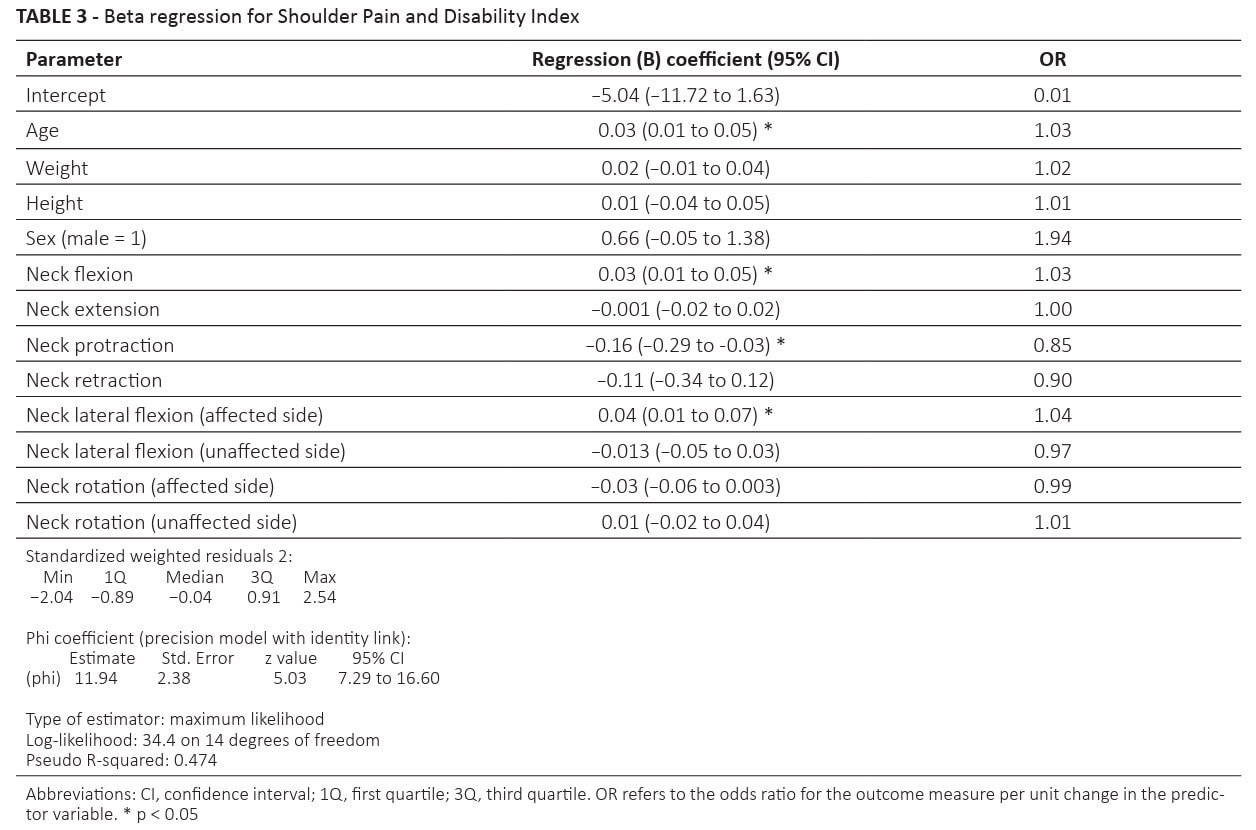

A model examining the relationship between neck AROM and shoulder pain and disability (SPADI) scores was constructed and revealed:

- With greater AROM for neck flexion, there was a tendency for higher shoulder disability scores. The OR=1.03 means that for each unit of change in the AROM for neck flexion, there is a slight increase in the odds of higher (worse) SPADI scores.

- If there is less neck protraction, this is associated with lower shoulder disability. For every unit increase in neck protraction, there’s a decrease in the odds of having higher SPADI scores (or an increase in the odds of having lower SPADI scores).

- When there is more lateral flexion AROM towards the affected shoulder (OR=1.04), this was also linked to higher shoulder disability.

- Age also played a role, with older participants tending to have higher disability scores (OR=1.03).

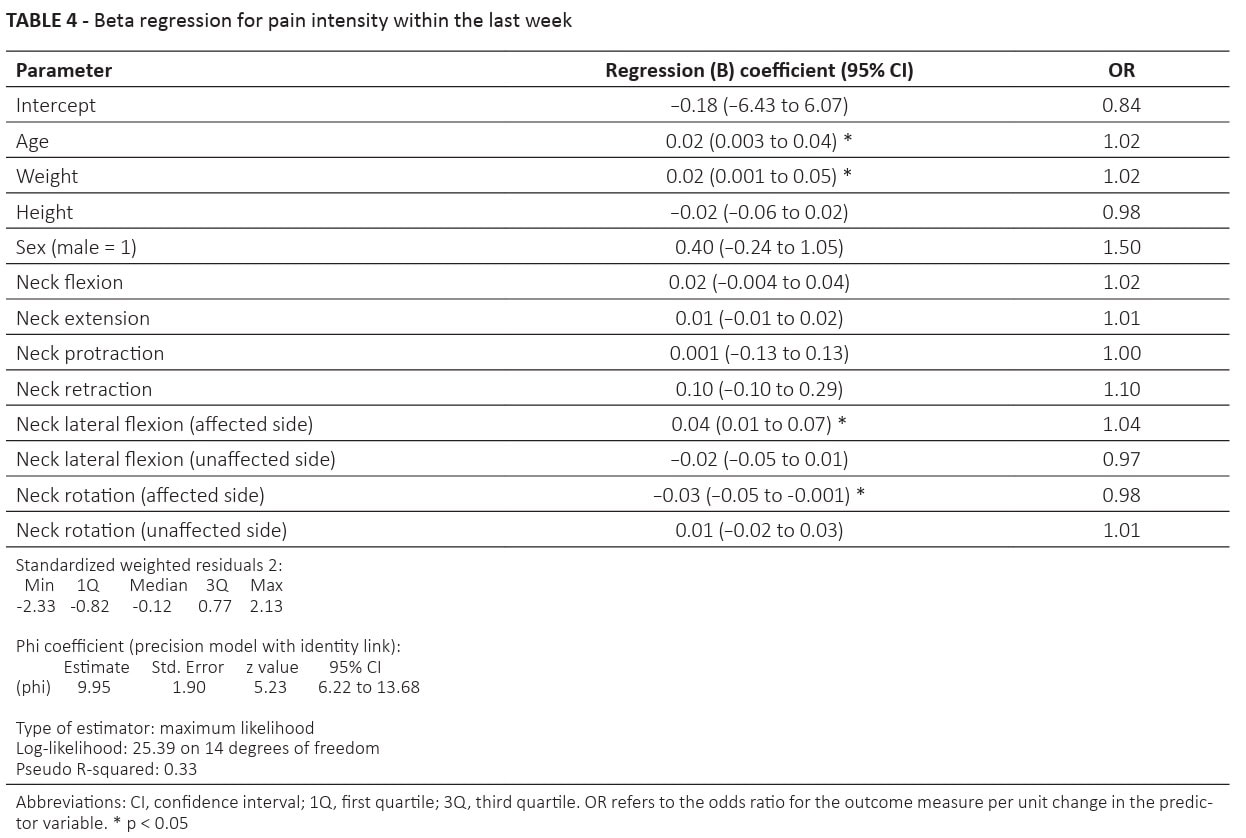

A second model examined the relationship of neck AROM and pain intensity during the past week and found:

- Greater neck lateral flexion towards the affected shoulder (OR=1.04) was positively associated with self-reported shoulder pain intensity during the last week. This means that greater neck lateral flexion towards the affected side was associated with higher shoulder pain intensity.

- Neck rotation toward the affected shoulder was negatively associated (OR=0.98) with self-reported shoulder pain intensity during the last week. This indicates that greater neck rotation towards the affected side was associated with lower shoulder pain intensity, or lesser rotation to the affected side is associated with higher self-reported pain intensity.

- Age (OR=1.02) and weight (OR=1.02) were also significant predictors: For each one-unit increase in age or weight, there is an estimated odds ratio of 1.02 for the expected increment in pain intensity. This indicates a slight positive association, meaning older individuals and heavier individuals tend to report slightly higher pain intensity.

Questions and thoughts

The odds ratios (ORs) in this study, like 1.03 or 0.85, are close to 1. ORs slightly above 1 mean there’s a very small increase in the likelihood of the outcome for each unit change in the predictor. An OR slightly below 1 means there’s a very small decrease in the likelihood of the outcome. So, when the ORs are close to 1, it indicates that while there might be a statistically detectable link, the practical impact or the strength of that connection is quite small. The authors themselves acknowledged this, stating that the “modest strength of the associations observed” means these results should be interpreted with caution.

This means that while these neck movements might be related to shoulder pain and disability, they likely only play a small part in the overall picture, and other factors are probably much more influential. This was also shown by the model’s low explained variance of 33%.

8 out of 50 people from the asymptomatic group reported having had neck pain outside of the 3 months before enrollment in the study. While this is not surprising, as neck pain has a high prevalence, it might be possible that those participants had experienced prior neck pain and developed functional limitations in the neck despite not reporting neck pain at the time of enrollment. The authors highlighted that this is a potential limitation, as neck problems experienced more than 3 months prior to study inclusion were not captured by a neck disability questionnaire. This could have affected the study’s results by blurring the lines between the truly asymptomatic group and those with underlying neck issues. Especially since cervical impairments may become asymptomatic over time. People experiencing cervical impairments without pain may have been included in the healthy controls, which reduces the value of a true control group.

Talk nerdy to me

To see if there were real differences between the people with shoulder pain and the healthy controls, a method called “ordinary least squares regression” was used. This is a fancy way of comparing averages while also making sure to account for other factors that could influence the results, like age, sex, height, and weight. This helps isolate the true differences related to shoulder pain. The analysis showed a significant between-group difference in neck AROM for rotation to the affected shoulder and greater pain sensitivity in the cervical spine (as seen by the lower PPTs) bilaterally in the RCRSP group compared to the healthy controls. This means that, at the time of assessment, the hypothesis of finding cervical impairments in RCRSP patients was confirmed.

Then the authors looked for connections between neck AROM and shoulder pain and disability, as measured by the SPADI, using a regression model. It shows how changes in neck movement might predict changes in shoulder pain or disability. The study reported “odds ratios (OR),” where an OR of 1 means no association, an OR greater than 1 means a positive association (as one goes up, the other tends to go up), and an OR less than 1 means a negative association (as one goes up, the other tends to go down).

Two regression models were constructed:

The model for predicting SPADI outcomes:

- This analysis showed a significant regression coefficient for age (OR=1.03), neck flexion (OR=1.03), and neck lateral flexion to the affected side (OR=1.04). This means that for every unit increase in the variables (for example age), the likelihood of having a higher SPADI score increases by 3% (1.03 – 1 = 0.03, or 3%). The same is true for neck flexion: with every degree increase in neck flexion, the odds of having higher SPADI outcomes increased by 3% (1.03 – 1 = 0.03, or 3%). For every degree increase in neck lateral flexion to the affected side, the odds of having worse SPADI scores increased by 4% (1.04 – 1 = 0.04, or 4%)

- A negative association was observed for neck protraction (OR=0.85). This means that for every degree increase in neck protraction, the odds of having a higher SPADI score are estimated to decrease by 15% (1 – 0.85 = 0.15, or 15%). In simpler terms, greater neck protraction is associated with a lower likelihood of increased shoulder pain and disability.

The model for predicting pain intensity during the past week:

- This analysis showed a significant regression coefficient for age (OR = 1.02) and weight (OR = 1.02). This means that for every unit increase in age, the likelihood of having higher pain intensity during the last week increases by 2%. Similarly, for every unit increase in weight, the odds of having higher pain intensity during the last week also increases by 2%.

- A positive association was observed for neck lateral flexion towards the affected shoulder (OR = 1.04). This means that for every degree increase in neck lateral flexion to the affected side, the odds of having higher pain intensity during the last week increased by 4%.

- A negative association was observed for neck rotation towards the affected shoulder (OR = 0.98). This means that for every degree increase in neck rotation to the affected side, the odds of having higher pain intensity during the last week are estimated to decrease by 2% (1 – 0.98 = 0.02, or 2%). In simpler terms, greater neck rotation towards the affected side is associated with a lower likelihood of increased shoulder pain intensity.

An important limitation lies in the study design. This study used a cross-sectional design to analyze two groups of patients at one moment in time. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships. Although the study observed cervical impairments in RCRSP patients, the current study cannot determine whether cervical impairments are a cause or consequence of RCRSP pain.

A strength lies in the use of validated devices like hand-held dynamometry, pain pressure thresholds, and the CROM device for ROM assessment, the standardized way of measuring the variables by two trained assessors, the good intra-rater reliability, and the use of the average of 3 repeated measurements for analyzing the data.

Take-home messages

This study measured differences in cervical mobility (AROM), pain sensitivity (PPTs), and neck strength between patients with rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP) and asymptomatic subjects. It concluded that RCRSP patients have reduced neck rotation towards the affected shoulder and increased bilateral neck pain sensitivity. The study also found associations between specific cervical movements and shoulder pain and disability. These findings suggest a potential interaction between the cervical spine and shoulder in RCRSP, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive assessment of both regions.

- Comprehensive Assessment is Crucial: Always include a thorough assessment of the cervical spine in patients presenting with rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP). The study highlights a potential interaction between the cervical spine and shoulder, suggesting that cervical impairments may contribute to shoulder dysfunction.

- Reduced Neck Rotation as an Indicator: Be aware that patients with RCRSP may exhibit reduced neck rotation towards the affected shoulder. This finding could indicate a contribution of the cervical spine to the patient’s symptoms, possibly even a subclinical cervical nerve root problem.

- Increased Pain Sensitivity in the Neck: Patients with RCRSP often show increased pain sensitivity in the cervical region (lower pressure pain thresholds) bilaterally. This suggests potential peripheral and central sensitization processes that should be considered in treatment planning.

- Consider Psychological Factors: Recognize that psychological factors like kinesiophobia (fear of movement) can play a significant role in RCRSP patients, potentially influencing reduced mobility and increased pain sensitivity. Addressing these factors may be an important part of a holistic treatment approach.

- Focus on Cervicothoracic Mobility: The study suggests that neck mobility is closely linked to shoulder function. Future research is needed to clarify this relationship, and interventional studies are warranted to evaluate the effects of improving cervicothoracic mobility on pain and functional outcomes in patients with RCRSP.

Reference

How Nutrition Can Be a Crucial Factor for Central Sensitisation - Video Lecture

Watch this FREE video lecture on Nutrition & Central Sensitisation by Europe’s #1 chronic pain researcher Jo Nijs. Which food patients should avoid will probably surprise you!