Updates on Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Many people are confronted with osteoarthritis (OA). As this condition cannot be cured, many people get to live with it for a significant part of their adult lives. The evidence recommends we use exercise therapy to reduce pain, improve joint function, and enhance the quality of life for individuals with OA. Unfortunately, despite exercise for knee OA being recommended as the first-line treatment, intra-articular injections, and oral analgesics remain the most common initial treatments (and their use even increased over time). Among the oral analgesics are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids.

What is the problem with opioids?

Different pharmacological interventions exist, so why just don’t prescribe them? People with OA may be prescribed opioids to ease pain. However, as OA is a chronic condition, the opioids are swallowed for a long time. Thorlund et al., 2019 found that people with knee and hip OA are among those who use opioids at disturbingly high rates. Examples of opioid drugs are:

- Codeine

- Fentanyl

- Hydrocodone

- Oxycodone

- Oxymorphone

- Morphine

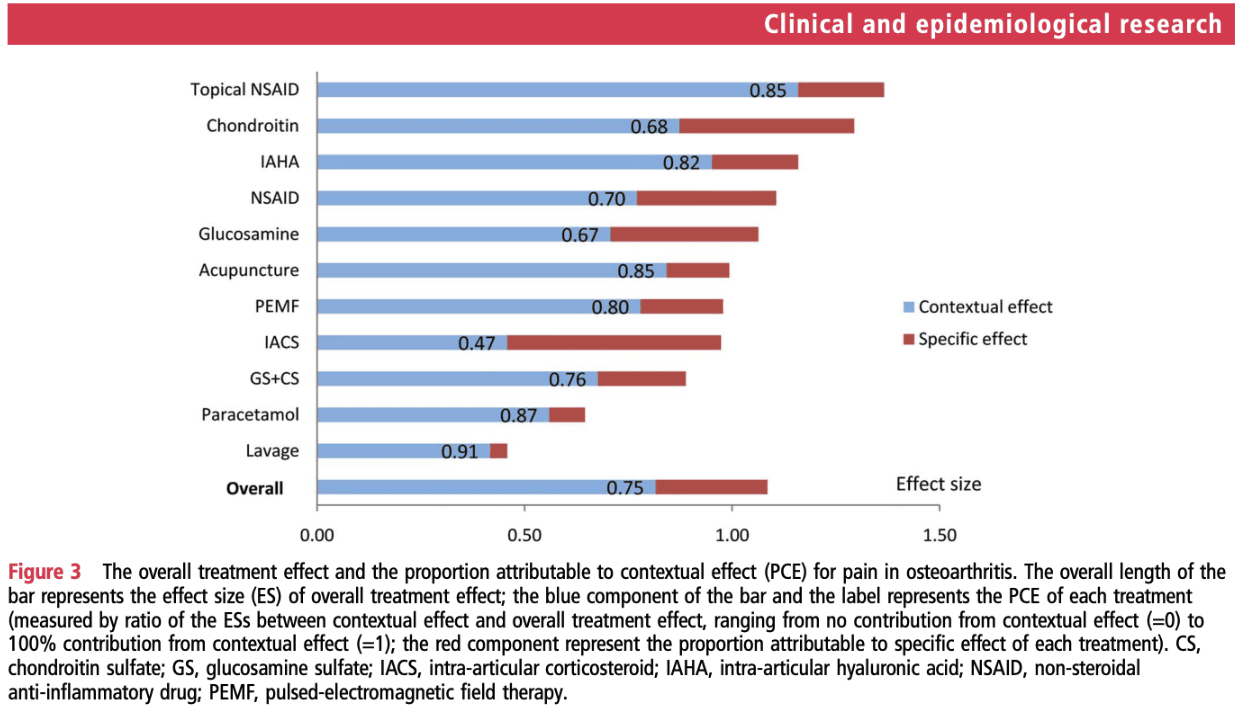

Several problems may arise when someone chronically takes opioids. Opioids are effective analgesic medications, but they frequently cause nausea, constipation, and sleepiness, and their use is linked to a significant risk of addiction. Nalini et al., 2021 showed that independent of the usual risk variables, long-term opiate use was linked to increased cardiovascular mortality. However, despite mounting evidence putting stated advantages into doubt and rising public knowledge of opioid hazards, their prescribing rates remained steady between 2007 and 2014.

Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, showed that Participants with or at risk of knee OA who took opioids and antidepressants with/without additional analgesics/nutraceuticals may have an elevated risk of recurrent falls after controlling for potential factors (Lo-Ciganic et al, 2017). They recommended that opioids and antidepressants should be used with caution.

Bearing these risks in mind, physiotherapy may be the key to obtaining better pain management and reducing the risk of opioid dependence in people with knee OA. The study by Kumar et al., 2023 found that people who got referred late to physiotherapy had a higher risk of opioid use than people with knee OA who got referred within 1 month of their diagnosis. Especially, active physiotherapy interventions led to lower risks of opioid use, and thus may have the potential to lower opioid dependence.

Does medication work after all?

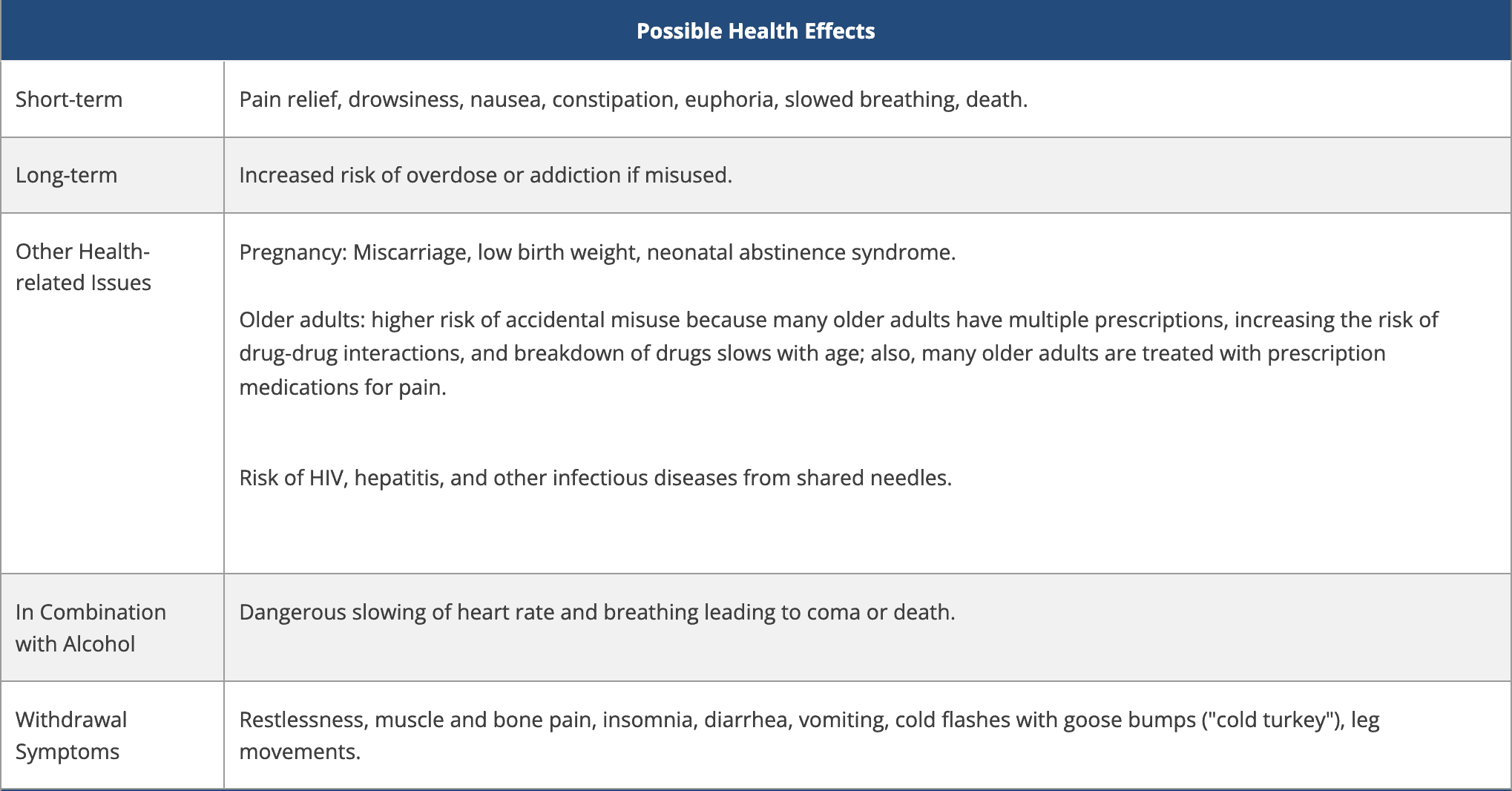

Can we say that treatments really do what they intend to do? This may be mindblowing, yet, Zou et al., 2016 analyzed the overall treatment effect and the percentage attributed to contextual effects found by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of diverse treatments for OA. They concluded that in OA RCTs, the majority (75%) of the overall treatment benefit is related to contextual effects rather than treatment-specific effects. Placebo, indeed. Of course, exercise therapy and physiotherapy also exert effects through a placebo. And rather than avoiding this, I think you should try to maximize your contextual effects. But when it comes to (intra-articular) pain medications (with adverse effects and associated risks), it should be encouraged to optimize your patient–practitioner interaction and other contextual factors that are within patients’ control instead of blindly prescribing pain medications and invasive treatments.

Why Exercise?

People may ask “Why would I exercise?”. Especially as other options exist (think of the analgesic drugs, injections, and joint replacement surgeries available). Vina et al., 2016 investigated the association between patient preferences for total knee replacement (TKR) with receipt of TKR. They found that someone who preferred to receive a TKR had two times higher odds of effectively receiving one. It appears that if the patient wants to receive a new knee, chances are high that the surgeon will follow. Patients often have incorrect expectations about a “new knee”. When these expectations are not met, the chances of the patient becoming dissatisfied are high, as shown by Bourne et al., 2010. Further, there is a limited understanding of how nonsurgical management options may work. This may lead to people wondering why they would exercise instead of opting for joint replacement surgery.

Besides exercise being able to improve symptoms of OA, it has the potential to exert positive disease-modifying effects. The degradation of the articular cartilage is the hallmark feature of OA. Yet we all learned that healthy bone and cartilage are maintained by dynamic processes on a cellular level, but these are influenced by mechanical loading. Also, the condition extends further than the joint space where remodeling and synovitis occur. It also affects the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

Furthermore, Henriksen et al. in 2016 concluded from their meta-analysis of Cochrane reviews, that exercise comes with comparable effects as analgesics but with fewer adverse events and risks associated. This was further endorsed by Weng et al., in 2022.

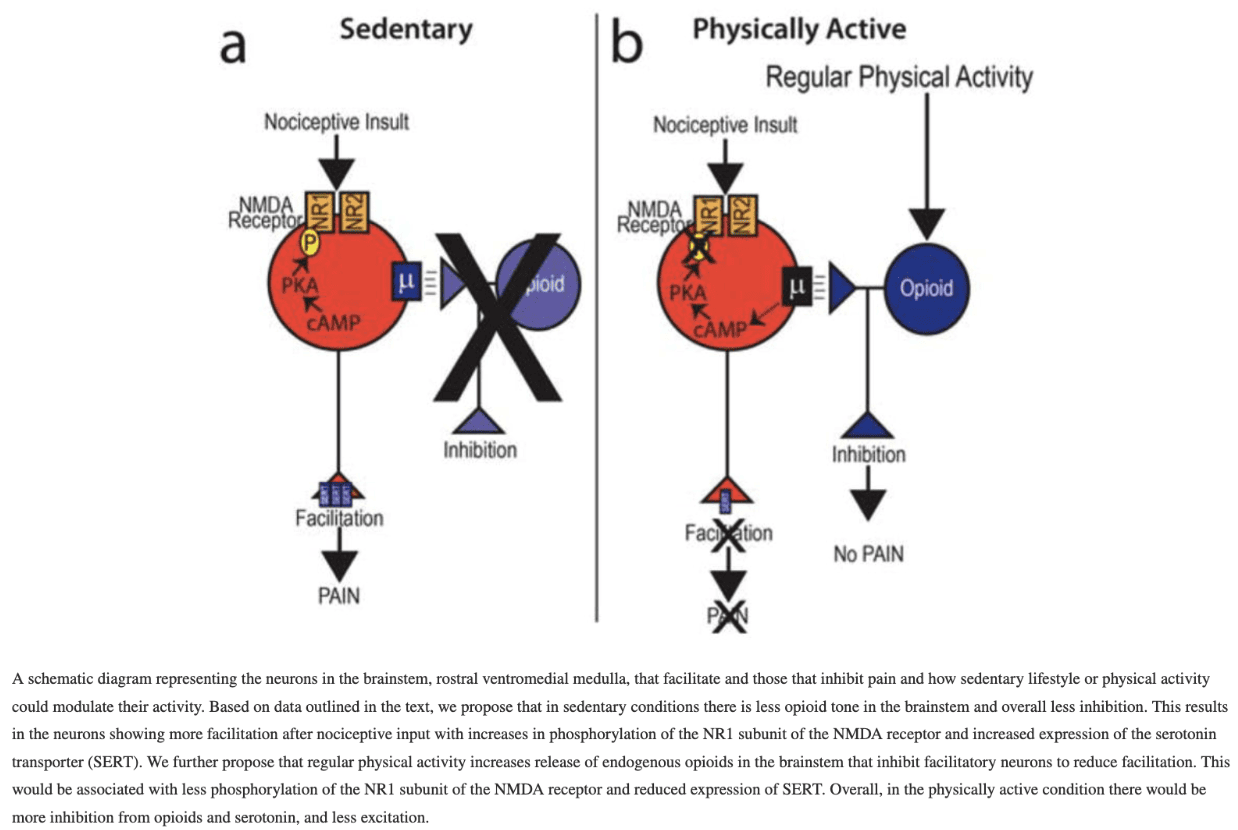

People may be afraid of increasing pain with exercise. Sluka et al. (2018) studied exercise-induced pain and analgesia. They proposed that “regular exercise alters the status of the immune system and central pain inhibitory pathways to have a protective effect against a peripheral injury. Physically inactive people lack this normal protective state that develops with regular exercise, which increases their chance of developing chronic, debilitating pain.” This study did not go into detail about OA, however, it shines a light on the beneficial effects of exercise. What we could propose is, since physically inactive people could experience flare-ups at the beginning of exercising, to adapt loads to their individual level—for example, using the Borg scale.

How do nonsurgical interventions improve OA symptoms?

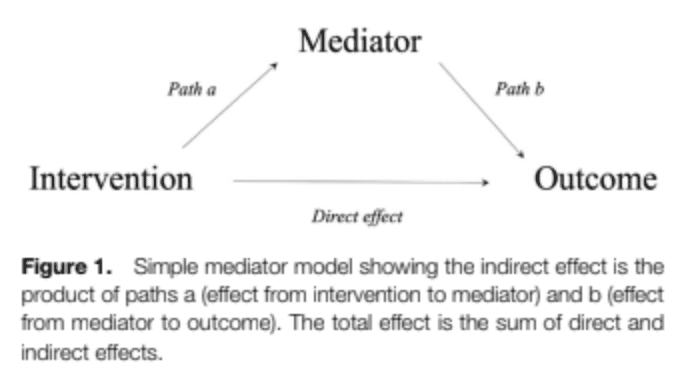

Here comes the study by Lima et al., in 2023 who investigated the mediators of nonsurgical interventions on the outcomes of pain and physical function. A mediator describes how an independent variable influences a dependent variable. So in our case, how does an exercise intervention affect the outcome of pain or function in people with knee OA. It is part of the causal pathway of an effect and tells you how or why an effect occurs.

Effects may occur directly or indirectly. A direct effect affects the outcome straightforwardly. But many times, this is not so simple. Interventions may improve certain outcomes through mediators. These variables may give more insight into the causal explanations and are important to better understand how interventions may work. In the figure above are mentioned “Path A” and “Path B”. It is important to learn about the mediators so we can tailor the interventions more confidently. If we would for example know that the mediator is affecting the outcome, but the intervention does not influence the mediator itself, it would be necessary to adapt the intervention or find other effective strategies.

Let’s use an example to clear this up. For example, if we know that for example, a diet (= intervention) would improve pain (= outcome) in someone with knee OA through a reduction in body weight (= mediator), we could certainly advise someone to alter their eating patterns. However, if the diet does not affect body weight, another type of diet that does result in weight loss may be more appropriate.

Pain

For the outcome pain, mediators of exercise were knee muscle perfusion, knee extensor strength, and self-efficacy. The mediators of the effect of diet and exercise on pain were changed inflammatory biomarkers, body weight reductions, and improvement in self-efficacy.

Physical function

Exercise mediates the effects on physical functioning by increasing the knee extensor muscle strength and improving knee pain. In contrast, diet and exercise mediates the effects through weight loss, changes in inflammation, and increased self-efficacy.

The recent individual patient data mediation study by Runhaar et al., 2023 however found that the only significant mediator of change in knee pain and physical function was the change in knee extension strength, but it only mediates around 2% of the effect. This keeps us aware of the need to take into account the other crucial factors which may include patient preferences, adherence, the importance of the therapeutic interaction, and the availability of resources while choosing exercise therapy.

Exercise works well, but what about timing?

The keynote of the study by Kumar et al. (2023) indicates that “earlier initiation of care could lead to more effective pain management and reduce reliance on opioids.” To birds with one stone! To note, currently, no randomized controlled trials have investigated the timing of initiation specifically. But from the study, we can say that fewer opioids were used (opioid use served as a proxy for the efficacy of pain management) when 6-12 supervised sessions were held in the people who already were prescribed opioids and in those who were opioid naive, the risk for chronic opioid use was lower with the same amount of sessions. When physiotherapy was initiated within one month of knee OA diagnosis, the risk of (chronic) opioid use was lower.

RUNNING REHAB 2.0: FROM PAIN TO PERFORMANCE

THE ULTIMATE RESOURCE FOR EVERY THERAPIST WORKING WITH RUNNERS

Challenges with strengthening in OA

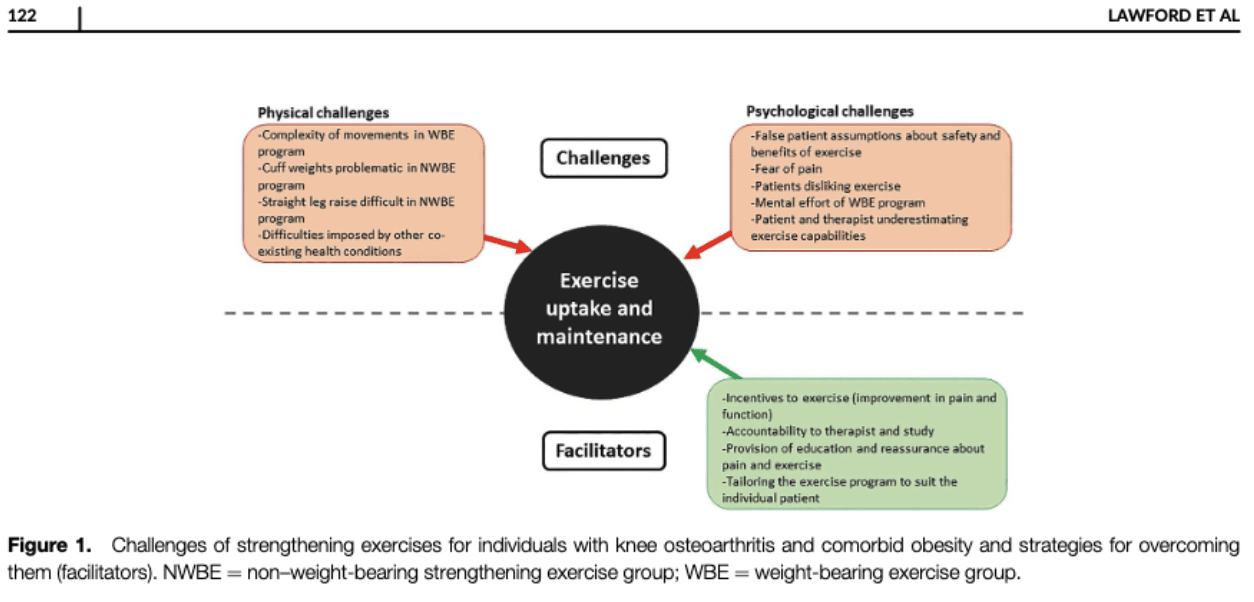

Several challenges and barriers to participation in strengthening exercises may arise. Lawford et al., in their RCT in 2022 explored challenges associated with the implementation of a home-based strengthening exercise program for individuals with knee osteoarthritis and comorbid obesity. They found that several challenges emerged on both a psychological (e.g. false assumptions about exercise, fear, underestimation,..) and physical (e.g. complexity of movement, weights,..) level.

Education and reassurance may be key to getting someone with false assumptions about exercise or fear to provoke symptoms to exercise. A tailored exercise program was seen as a facilitator of exercise uptake and maintenance. Both the physical and psychological challenges can be addressed in the physiotherapy consultation. If someone experiences difficulties with for example heavy weights and this gets them demotivated from exercising, there may be other options to increase exercise loads without the use of these extra weights.

Does the type of exercise influence outcomes?

Goh et al., from their meta-analysis in 2019 concluded that aerobic and mind-body activities were found to be the most effective for pain and function, while strengthening and flexibility/skill exercises may be the second best for a variety of outcomes. Although mixed exercise is the least effective form of treatment for knee and hip OA, it nevertheless outperforms standard care.

When exercise doesn’t help – when to refer to the orthopedic surgeon?

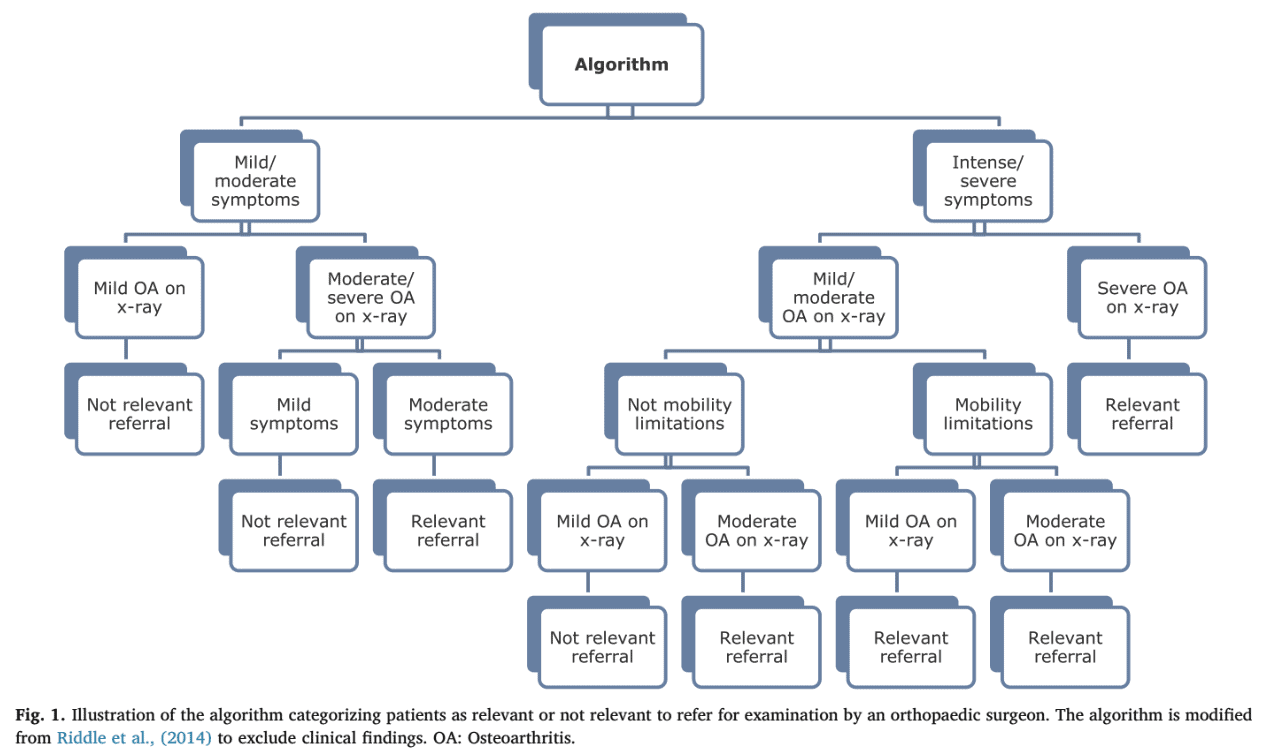

One of the problems in the orthopedic department is the long waiting period before someone can be seen by a surgeon. One of the reasons therefore is that many patients who are referred to orthopedic clinics are not eligible for surgery and, thus their referral was irrelevant. But when do we need to refer to a surgeon in people with knee OA? The study by Mikkelsen et al. in 2019 tried to develop a tool to define whether a referral to an orthopedic knee surgeon was relevant or not. To improve the usability of the tool, the algorithm was based on patient-reported outcomes and radiographic findings because these data are more easily accessible in primary care settings.

The algorithm’s performance did not meet the predefined acceptable level. Nonetheless, it can help us to determine the majority of patients who should be sent to the orthopedic outpatient clinic. It should be noted that it was less effective at determining which patients did not require an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon. Let’s look at the variables needed for someone to be sent to the orthopedic department. The algorithm classified people as a relevant referral when they had:

- Moderate knee symptoms (KOOS 12-22) with moderate to severe OA on XRay (Kellgren-Lawrence scale 3-4)

- Intense to severe knee symptoms (KOOS 23 and higher) without mobility restrictions but moderate radiographic OA (Kellgren-Lawrence scale 3)

- Intense to severe knee symptoms (KOOS 23 and higher) with mobility restrictions and mild to moderate radiographic OA (Kellgren-Lawrence scale 0-3)

- Intense to severe knee symptoms (KOOS 23 and higher) with severe radiographic OA (Kellgren-Lawrence scale 4)

This algorithm was able to identify 70% of people who should be sent to the orthopedic surgeon as it showed a 70% sensitivity. This was determined by analyzing which of the referred patients were effectively treated by the orthopedist. However, specificity was low (56%) and thus the algorithm could not accurately predict those who were not relevant to refer. The algorithm was good at predicting people who needed a total knee replacement with a 92% sensitivity.

The problem with the abovementioned algorithm is that the KOOS symptoms are used as a first triage but the effective decision is taken based on the radiographic severity of OA. Healthcare is stepping away from treating imaging findings. Holden et al. in 2023 indicated that targeting people with higher levels of OA-related pain and disability for therapeutic exercise may make sense because they benefited from it more than people with lower levels of pain severity and better physical function at baseline. This referral algorithm, however, refers more frequently to the orthopedic surgeon in case of severe symptomatology. This discrepancy should be further investigated. Yet an important side note, not included in this algorithm but mentioned by the authors is the response to conservative care. They argued that the variable “not responding to non-surgical treatment” would be appropriate to include in the algorithm as this is also reflected by the clinical guidelines. So as the guidelines recommend, I would certainly first opt for active exercise-based physiotherapy treatment targeted at the individual level.

Conclusion

Patients with OA who engage in dynamic moderate exercise can reduce their symptoms and possibly even slow the progression of their OA. Exercise affects every tissue within the articular joint and can effectively slow the course of osteoarthritis by reducing inflammation and catabolic activity, boosting anabolic activity, and preserving metabolic homeostasis. Exercise has similar effects to oral NSAIDs and paracetamol on pain and function. Given its outstanding safety profile, exercise should be given increased importance in clinical care, particularly in older adults with comorbidity or who are at higher risk of adverse events due to NSAIDs and paracetamol. Earlier initiation of care could lead to more effective pain management.

Thanks a lot for reading!

Cheers,

Ellen

References

Ellen Vandyck

Research Manager

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.