SLAP Lesion / Superior Labrum Tear | Diagnosis & Treatment

SLAP Lesion / Superior Labrum Tear | Diagnosis & Treatment

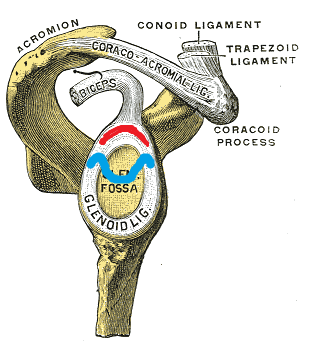

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilagenous structure that runs circumferentially around the rim of the shallow bony glenoid fossa, deepening the socket and acting as a passive stabilizer to prevent humeral head subluxation. The labrum also serves as an attachment site for capsuloligamentous structures, such as the glenohumeral ligaments and the long head of the biceps (Calcei et al. 2018).

SLAP stands for Superior labral tear, anterior to posterior, and comprises four major injury patterns as a cause of pain and instability, particularly in the overhead athlete (Ahsan et al. 2016).

Snyder et al. (1990) first described four injury patterns in 27 patients:

- Type I: Degenerative fraying of the superior labrum free edge with intact peripheral attachment and stable biceps tendon anchor. This pattern is very common amongst middle-aged and elderly populations, suggesting that it may be a degenerative finding that is not a definitive source of pain

- Type II: Degenerative fraying with an additional detachment of the superior labrum and biceps from the glenoid resulting in an unstable labral-biceps anchor (marked with red in the illustration)

- Type III: Bucket-handle tear of the superior labrum with an intact biceps tendon anchor (marked with blue in the illustration)

- Type IV: Lesions include a displaced bucket-handle labral tear with extension into the biceps tendon root

Ahsan et al. (2016) stress that the original description by Snyder lacks adequate reproducibility, which might partly be attributable to the difficulty in understanding even normal superior labral anatomy and age-related changes that can occur.

There are two main theories on the pathogenesis of type II SLAP lesions in athletes (Change et al. 2016):

- Cadaveric and arthroscopic demonstrations of impingement of the posterosuperior labrum between the greater tuberosity and glenoid with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation (ABER) led to the hypothesis that posterosuperior impingement causes SLAP and cuff tears.

- Other investigators favor a peel-back mechanism, wherein humeral hyper-external rotation in the late cocking phase generates a posteriorly directed torsional force on the biceps tendon, leading to twisting and peel-back and detachment of the biceps root and posterosuperior labrum from the underlying glenoid cartilage.

Given how often posterosuperior impingement, SLAP lesions, and rotator cuff undersurface tears occur concurrently, both of these proposed mechanisms likely contribute to the pathogenesis of SLAP lesions.

Acute injuries can be caused by a fall by a fall onto the outstretched arm or an unexpected pull on the arm, e.g., when losing grip of heavy objects or sudden traction (e.g., high bar exercises, hold off bodyweight in dropping rock climbers). Furthermore, injury can occur following direct contact of the adducted shoulder which an opposing player (in e.g. rugby) or to the surface (Popp et al. 2015).

Epidemiology

Schwartzberg et al. (2016) report a prevalence of up to 72% diagnosed by MRI in the asymptomatic population between 45 and 60 years of age.

Landsdown et al. (2018) retrospectively analyzed shoulder MRIs performed in patients with shoulder pain and found that the prevalence of SLAP tears increases with age. In the study, MRIs from patients between 51-65 were twice as likely to show a SLAP tear and in patients older than 65 the chance of a SLAP tear increased fourfold compared to 35-50 years of age.

On the other hand, Pappas et al. (2013) investigated the prevalence of labrum tears in 102 cadavers with an average age of 80.6 (range 57 – 96) and found a low prevalence of 9.8% with 8.8% classified as type I and 0.98% classified as type II lesions.

Weber et al. (2012) report that SLAP repairs made up 9.4% of all arthroscopic surgeries for the shoulder in the United States between 2003 and 2008 with increasing numbers.

Of those SLAP repairs, 78.4% were performed in men (mean age 36.4) and 21.6% in women (mean age 40.9).

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Picture & Examination

Signs & Symptoms according to Calcei et al. (2018) are:

- Anterior shoulder pain

- Repetitive trauma through overuse

- Throwers complain about velocity and report clicking, popping during the late cocking phase of the throwing motion

- Tennis and volleyball players may complain of pain during cocking phase of the serve

- Concomitant injuries such as rotator cuff pathology and instability

Examination

Ahsan et al. (2016) state that given the difficulties in reliably classifying SLAP lesions based on arthroscopic videos, it is not surprising that physical examination maneuvers and MRI findings are reported to be unreliable in correctly diagnosing SLAP lesions.

Mathew et al. (2018) point out that a key aspect of patient history-taking is to look at the provocative phase or phases of pitching throwing in an overhead athlete.

The reason is that posterior pain in the late cocking phase could indicate a posterior superior labral tear and supraspinatus-infraspinatus junction due to internal impingement.

Posterior pain during the release or follow-through on the other hand might be indicative of the eccentric failure of the rotator cuff. Anterior pain during the cocking phase is associated with some degree of anterior instability of multifactorial origin. At last, anterior pain during the terminal phase of the throw might indicate mechanical impingement of the biceps or coracoid impingement.

Overhead throwers often present with glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD), which should be assessed first. On top of that, scapular dyskinesis is often present and should be evaluated in a second step. While we mentioned in the “Scapular Dykinesis” unit that scapular dyskinesis might actually be a sport-specific adaption, it might be a risk factor for the development of shoulder pain in athletes performing at elite levels.

Two possibly helpful clusters have been evaluated in order to exclude a SLAP lesion:

1) The “3-Pack” Examination consists of O’Brien’s Active Compression Test (ACT), resisted throwing test, and palpation of the bicipital tunnel described by Taylor et al. (2017).

The author describes that both a negative ACT (with sensitivity values ranging from 88-96% and specificity ranging from 46-64%) and/or a negative palpation test (Sensitivity: 92-98%/ Specificity: 52-73) are helpful in the exclusion of lesions to the biceps-labrum-complex.

2) The cluster described by Schlechter et al. (2009) consists of the Active Compression Test and the Passive Distraction Test (PDT). In the case of 2 positive tests, the cluster yields a LR+ of 7.0 and a negative LR- of 0.33 in the case of two negative outcomes.

Rosas et al. (2017) have conducted a literature review and have come up with a test cluster. They found that the uppercut test combined with tenderness to palpation of the long head of the biceps had the highest accuracy to diagnose pathology of the proximal biceps with a sensitivity of 88.3% and a specificity of 93.3%. Although accuracy seems to be high, this combination has not been confirmed by other studies or reviews yet, which is why we give it a moderate clinical value in practice.

TWO MYTHS BUSTED & 3 KNOWLEDGE BOMBS FOR FREE

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

Nonoperative management has demonstrated success, including in overhead athletes, and therefore should be the first line of treatment for athletes with biceps and superior labral-complex injuries (Calcei et al. 2018). Physiotherapy should focus on functional impairments like range of motion (thereby focusing on possible concomitant GIRD), glenohumeral and scapulothoracic strength, and coordination. Mathew et al. (2018) report a higher success rate in professional baseball players with directed rehabilitation that focuses on the flexibility of the posterior capsule and scapula positioning compared to surgical treatment.

Schrøder et al. (2016) compared two common surgery techniques (labrum repair and biceps tendon arthrodesis) with sham surgery in 118 surgical candidates with SLAP II lesions. At six months and two-year follow-up, neither labral repair nor biceps tenodesis had any significant clinical benefit over sham surgery for patients with SLAP II lesions in the population studied. On top of that, post-operative stiffness occurred in five patients after labral repair and in four patients after tenodesis.

References

Mathew, C. J., & Lintner, D. M. (2018). Suppl-1, M6: Superior Labral Anterior to Posterior Tear Management in Athletes. The open orthopaedics journal, 12, 303.

Moore-Reed SD, Kibler WB, Sciascia AD, Uhl T. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for treatment of patients with suspected SLAP tears. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2014 Dec 1;30(12):1540-9.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

It’s Time to Stop Nonsense Treatments for Shoulder Pain and To Start Delivering Evidence-based Care

What customers have to say about this course

- Tineke De Vries26/01/25Goede cursus. Goede cursus, gericht op de praktijk Veel geleerd. Met name wat betreft de opbouw van de oefeningenDempsey Thiele02/01/25Overzichtelijk en praktisch! Ik heb de cursus met plezier afgemaakt. Ik denk dat dit een relevante cursus is voor iedere fysiotherapeut die meer inzicht wil krijgen over de huidige evidence omtrent schouder rehabilitatie. Alle informatie wordt overzichtelijk aangeboden.

Ik kan weer kritisch aan de slag mijn patiënten te helpen in de toekomst! - Carlijn Duursma27/12/24Goede cursus Veel verdieping. duidelijke uitleg. misschien wat tekeningen toevoegen voor extra verduidelijking. Veel geleerd.Vanessa Burnet22/12/24Leerzame cursus Opfrissing van kennis wat is weg gezakt.

- Paul Mensink15/12/24Paul Mensink High level literature composed course, videos are perfect examples for used techniques and exercisesFrank Kleyn12/12/24CRSP Ik kan bovengenoemde cursus zeer aanbevelen , nieuwste inzichten , zin en onzin van Subacromiale ruimte , de duidelijke vertaling naar de praktijk en de behandeltafel .

- Marty26/11/24RCRSP CURSUS Niet heel veel nieuws maar wel een goed overzicht en duidelijke uitleg over biomechanica.

Goede filmpjes van Filip en technieken ook goed uitgelegd.

Goede toetsen die de lesstof vrij compleet behandeld..

Website werkt naar mijn mening niet goed. Nogal onoverzichtelijk…

Vergt wat tijd om er mee om te gaan maar voordeel van de cursus is de gunstige prijs per accreditatie punt. Netjes.maria Kramer01/11/24goede cursus voor rcrsp Goede cursus met veel praktische vaardigheden en oefeningen die je direct kunt toepassen, aanrader. - Erik Versluis13/08/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain RCRSP by Filip Struijf

State of the art course and very useful for physiotherapists with shoulder expertise or who want to further develop their skills in research and treatment of patients with shoulder complaints. A nice addition is a shoulder case in which you can process the knowledge you have recently acquired.

A major advantage is the possibility to read the course material offered and to watch the video material again.Birgit Schmitz28/04/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain RCRSP

Ik vond het een waardevolle cursus met onderbouwd wetenscahppelijk onderzoek dat ondersteunt in mijn praktisch handelen. Ik heb al een nieuwe cursus uitgezocht. 🙂 - Thijs de Jager22/04/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain GOEDE RCRSP CURSUS.

Over het algemeen een goede cursus waarbij ik veel ben opgestoken. Goede, evidence based informatie met hier een daar wat uitleg video’s die zeker helpvol waren. Het is ook fijn dat je onder de cursusonderdelen vragen kan stellen en hier een antwoord op kan verwachten van Filip zelf. 4 sterren i.p.v. 5 sterren omdat ik graag meer duidelijkheid en uitleg in video format over de oefeningen had willen zien. Er worden een hoop oefeningen getoond maar het is aan de cursist zelf om te bedenken welke in te zetten in de praktijk.Larson de Neve16/04/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain GOOD COURSE

Good theoretical and practical course with exercises that you can immediately use in practice. - Beppeke Molenaar13/04/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain OVERALL A GREAT COURSE

This is a very informative and comprehensive course.

Some of the quiz answers that are correct are counted as incorrect, which is a pity.

(Comment Physiotutors: We are currently doing an overhaul of our quizzing system and have fixed this issue now.)Willem Zee28/01/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain PRIMA CURSUS!

goed te doen, uiterst praktisch - Jason Pearson11/01/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain RCRSP COURSE

Very satisfied with this course. Provides a great framework with which to build your assessment and rehabilitation strategiesMichal Wajdeczko09/01/24Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain Ik ben super blij ermee.

Het was een zeer interessante training. Het cursus was rijk met ge-update informatie, alles wordt volledig en transparant uitgelegd. Ik moet ook toevoegen dat deel van nuttige sets oefeningen briljant is! Veel nuttige tips en combinaties om rotator cuff pijn te kunnen verminderen en alle spieren efficiënt te trainen. Ik ben er trots op dat ik weer mijn kennis en competenties kon ontwikkelen en om mijn patiënten een professionele benadering van schoudercomplexe aandoeningen te kunnen bieden.

Super bedankt!! - Ante Houben30/12/23Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain RCRSP

This course is well designed and based on solid evidence. The information is presented in a structured manner, using text, images and videos to enhance understanding. In addition, I appreciated the course’s emphasis on effectively conveying this information to patients. However, I wished the exercise therapy was more extensive.

Naomi Tiller20/12/23Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain RCRSP COURSE

Fantastic course that’s easy to follow, up to date and evidence based. I’ve immediately been able to implement what I’ve learnt in to my own work which has given me a lot more confidence as well as made it more enjoyable! A good refreshed for me on how the rotator cuff works, a better understanding of how to treat these problems and better communicate with my patients as well as exercise inspiration (always appreciated!). Overall very happy to have done this course!

Super bedankt!! - Stijn de Loof17/12/23Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain GOOD THEORY, LESS EXERCESIS

I liked the theoretical part of the course. A good refresher about the shoulder and rotator cuff with new insights

I was a bit disappointed in the part ‘exercises’. They were super basic and without explinations.Mehdi Benkirane24/11/23Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain REVIEW

Très bon cours, je le recommande pour se remettre à jour sur les tendinopathies de l’épaule.