Sacroiliac Joint Pain & Dysfunction | Diagnosis & Treatment

Sacroiliac Joint Pain & Dysfunction | Diagnosis & Treatment

The sacroiliac joint lies between the sacrum and the ilium and connects the spine to the pelvic bones. The SIJ transfers large bending moments and compression loads to the lower extremities and acts as a stress reliever in the ‘force–motion’ relationships between the trunk and lower limb. However, the joint does not have as much stability of its own against the shear loads but resists shear due to the tight wedging of the sacrum between hip bones on either side and the band of ligaments spanning the sacrum and the hip bones. Due to these, the sacrum does not exhibit much motion with respect to the ilium (Kiapour et al. 2020). An in-vitro study by Hammer et al. (2019) showed that rotation around the longitudinal axis in a loaded position with 100% of simulated body weight was as small as 0.16° and an inferior translation of the sacrum relative to the ilium was 0.32 mm. Sacroiliac joint flexion-extension rotations were minute (< 0.02°). In a real-life situation, Kibsgard et al. (2014) used radiosteriometric analysis of anesthetized patients with persistent SIJ pain performing the single-leg stance test. They found a total of 0.5° of rotation, while no translations were observed. The average mobility in men is about 40% less than in women (Vleeming et al. 2012).

A forward rotation of the sacrum in relation to the ilia is called nutation and a backward rotation of the sacrum in relation to the ilia is called counternutation. During flexion of the hip, the ipsilateral ilium glides backward and downwards across the sacrum and compresses against it, pivoting at the pubic symphysis. During extension, the ilium glides forwards and flares away from the sacrum (Bogduk 2012, no direct link available).

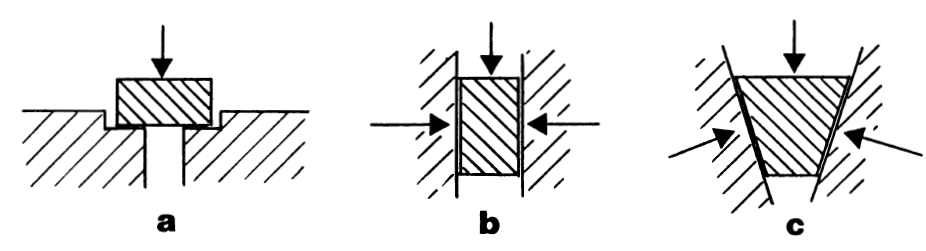

Form closure: Form closure (a in the figure below) is a theoretically stable situation with closely fitting joint surfaces, where no extra forces are needed to maintain the state of the system (Pool-Goudzwaard et al. 1998). In the SIJ, form closure is achieved through the configuration of the interfacing joint surfaces, along with dorsocranial ‘wedging’ of the sacrum into the ilia and the complementary ridges and grooves of the articular surfaces of the SIJs (Vleeming et al. 2012). If the sacrum could fit in the pelvis with perfect form closure, mobility would be practically impossible. Extra forces are needed for the equilibrium of the sacrum and the ilium during loading situations (Pool-Goudzwaard et al. 1998).

Force closure: Force closure (b in the figure below) is the effect of changing joint reaction forces generated by tension in ligaments, fasciae, and muscles, and ground reaction forces. In force closing the pelvis, the nutation of the sacrum is essential. Nutation represents a movement that tightens most of the SIJ ligaments, among which are the vast interosseous and dorsal sacroiliac ligaments thereby preparing the pelvis for increased loading (Vleeming et al. (2012). Especially during unilateral loading of the legs, this system has to become active.

Together (c in the figure above), Pool-Goudzwaard and colleagues term this shear prevention system the “self-bracing or self-locking mechanism” of the SI-joint.

Ligaments: Nutation of the sacrum tightens the interosseus and sacrotuberous ligaments, leading to more friction at the joint surfaces, hence more stability of the SI joints (Pool-Goudzwaard et al. 1998). Nutation occurs during loading situations such as transferring from lying supine to sitting and standing. Counternutation on the other hand winds up the dorsal sacroiliac ligament.

Muscles: Several muscles can contribute to force closure of the SI joint either directly or via the thoracolumbar fascia. Pool-Goudzwaard et al. (1998) describe three muscles slings that can be energized:

- Longitudinal sling: Multifidus attaching to the sacrum, deep layer of the thoracolumbar fascia, long head of the biceps attaching to the sacrotuberous ligament

- Posterior sling: Latissimus dorsi and contralateral gluteus maximus, biceps femoris

- Anterior sling: Pectorals, external oblique, transverse abdominis and internal oblique

- Other muscles: Diaphragm, pelvic floor (in females, simulated tension in the pelvic floor muscles stiffened the SIJ with 8.5%. In males, no significant changes seem to occur. In both sexes, these muscles can generate a backward rotation of the sacrum (Pool-Goudzwaard et al. 2004)

SIJ pain is defined as pain localized to the region of the SIJ that is reproducible by stress and provocation tests of the joint and that completely resolves after infiltration of local anesthesia (Merskey et al. 1994, no direct link)

Epidemiology

Simopoulos et al. (2012) performed a systematic analysis of sacroiliac joint interventions and found a point prevalence for SIJ pain amongst patients with low back pain of 25%. In a large-scale study by Ostgaard et al. (1991), the authors found a 49% 9-month period prevalence rate for LBP among pregnant women, with SIJ pain comprising the majority of cases. Eno et al. (2015) examined the prevalence of SIJ degeneration in asymptomatic adults. Sixty-five percent of the included subjects had signs of radiologic degeneration of the SIJ with 30.5% classified as substantial. Furthermore, the prevalence increased with age with 91% of the subjects showing degeneration above the age of 80.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Several mechanisms of injury have been linked to the development of sacroiliac joint pain, including a direct fall on the buttocks, a rear-end or broad-side type motor vehicle accident, and an unanticipated step into a hole or from a miscalculated height (Simopoulos et al. (2012). In a study performed on 54 patients with suspected sacroiliac joint syndrome, Chou et al. (2004) found that 44% of patients cited a specific traumatic event, 21% reported a cumulative injury, and 35% had spontaneous or idiopathic onset of sacroiliac joint pain. Other risk factors mentioned in the literature are motor vehicle accidents, leg length discrepancy, fusion surgery, anterior dislocation, and inflammatory and degenerative SIJ disease. Furthermore, pregnancy can result in SIJ pain by virtue of weight gain, exaggerated lordotic posture, third-trimester hormone-induced ligamentous relaxation, and pelvic trauma associated with parturition (Cohen et al. 2013).

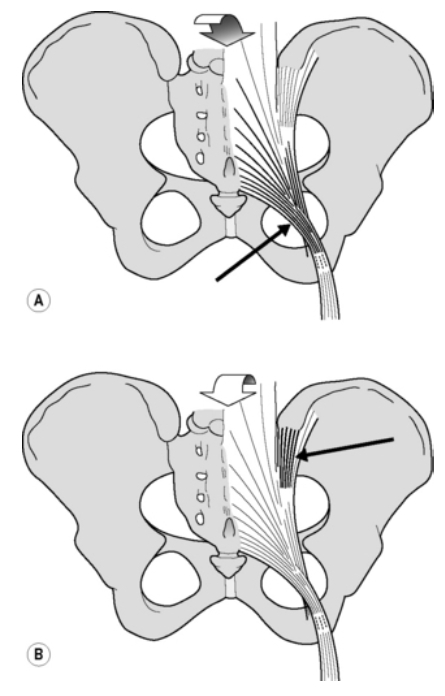

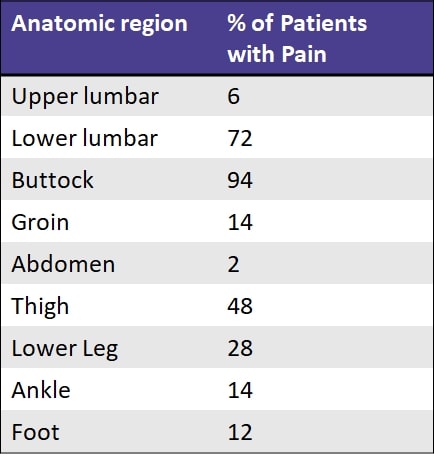

A study by Slipman et al. (2000) observed the pain referral zones of patients who demonstrated a positive diagnostic response to an SIJ injection. They found the following referral zones:

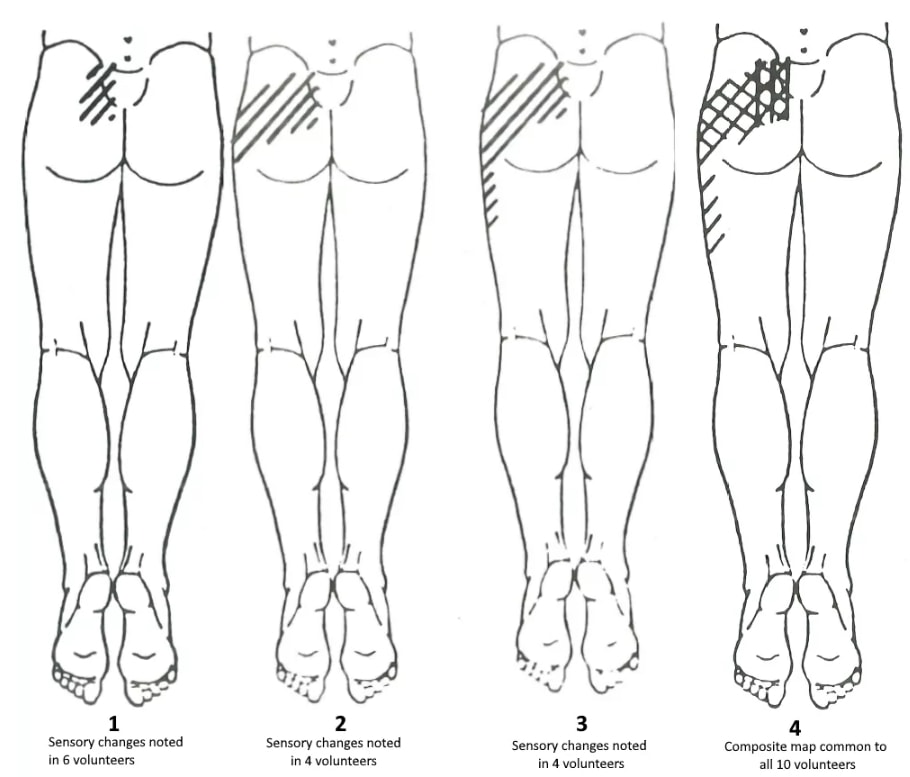

These findings are similar to what Fortin et al. (1994) described. According to their findings, sensory examination immediately after sacroiliac injection revealed an area of buttock hypesthesia extending approximately 10 cm caudally and 3 cm laterally from the posterior superior iliac spine. This area of hypesthesia corresponded to the area of maximal pain noted upon injection:

Given the innervation of the SIJ anteriorly from the branches of the lumbosacral trunk, superior gluteal nerve, obturator nerve (L2-S2), and posteriorly from the lateral branches of the posterior rami (L4-S3) a widespread distribution of symptoms seems plausible (Forst et al. 2006).

The findings from Fortin also resulted in the Fortin Finger Test (Fortin et al. 1997). This test is scored positive for SIJ Pain in case a patient points inferomedial below the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) within 1 cm when asked to point to the region of pain with one finger.

Examination

Another pain provocation cluster for sacroiliac joint pain is the Cluster of van der Wurff.

If you would like to obtain more information about individual tests for the SI joint check out our wiki pages below:

- Gaenslen’s Test

- Distraction Test

- Sacroiliac Compression Test

- Thigh Thrust Test

- Yeoman’s Test

- Patrick’s Test

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

If you are unfamiliar with or need a refresher, sacroiliac movement dysfunction describes excessive or restricted joint movement between the sacrum and one or both ilia. You may have heard of an upslip or downslip. The myth that once and for all has to stop is that you can palpate movement at the SI Joint. For a start, movement at the SI joint is minimal to non-existent. From 1-2° degrees in young individuals to virtually no movement in the elderly as the joint progressively stiffens.

So, do you feel confident palpating such movement in a patient using one of these tests? You might be, but even highly trained clinicians cannot reach a consensus on what constitutes SI joint dysfunction as has been shown by Riddle et al. (2002) and Dreyfuss et al. (1996) who report poor inter-rater reliability for common tests such as the Gillet or Standing Bend over test.To put it frankly. Assessing SI joint motion manually is like reading braille through a steak. Thanks to David Poulter at this point for lending the quote. In case you’re not convinced yet, Kibsgaard et al. (2014) used radiostereometric analysis and found a total of 0.5° of movement and conclude that even with highly sophisticated laboratory measurements SI joint movement was close to not measurable.

Another thing we have been taught as well and that lots of physios like to do is to examine pelvic tilt by measuring the angle between the anterior and posterior superior iliac spines. Here the posterior superior iliac spine should be higher than its anterior counterpart resulting in an angle of around 15°. However, research has shown that even in a small sample of both male and female pelvises that there is up to 11° of difference in that angle. From steeper angles of up to 23° to virtually horizontal alignment and even marked side-to-side differences. So taking these natural anatomical variations into account further devalues manual assessment of SI joint movement.

But we have all seen or heard of a patient with low back pain based on an assumed SI joint dysfunction that received a manipulation to the joint and had pain relief. Tullberg et al. (1998) showed that there is no change in the position of the sacrum and ilia after a manipulation. So the assumption of repositioning any upslip, downslip, or other dysfunction is further refuted. The mechanism of why someone might feel better after manipulation is still not exactly known.

MASSIVELY IMPROVE YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LOW BACK PAIN FOR FREE

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

How then do we manage patients having a high probability of SIJ pain following the provocation tests of Laslett et al. (2005)? Unfortunately, there are no randomized trials of different treatments for patients with pain confirmed as arising from the SIJs. However, the literature concerning pelvic girdle pain (PGP) associated with pregnancy offers some good-quality information in this regard (Laslett et al. 2008). Some 54% of women with pregnancy-related PGP satisfy the SIJ provocation cluster (Gutke et al. 2006).

Stuge et al. (2004) compared pelvic stabilization exercises with a control group receiving different physiotherapy methods such as massage, relaxation, joint mobilization, manipulation, electrotherapy, hot packs, mobilizing, and strengthening exercises. The intervention group mainly focuses on the deep muscles such as the transverse abdominis and multifidi, but also on more superficial muscles such as the gluteus maximus, latissimus, oblique abdominals, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and hip abductors and adductors. They found that specific stabilization training resulted in a 50% reduction in disability, a 30 mm reduction in pain on a 100 mm VAS scale, and an improvement in quality of life at one year compared to insignificant changes in the control group.

On the other hand, an RCT by Gutke et al. (2010) found that a home-exercise program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises targeting the local muscles was no more effective in improving the consequences of persistent postpartum pelvic girdle pain than the clinically natural course. Regardless of whether treatment with specific stabilizing exercises was carried out, the majority of women still experienced some back pain almost one year after pregnancy. The training in their study focused mainly on the local stabilizing muscles, while Stuge et al. (2004) also included training of global muscles. This led Gutke et al. (2010) to doubt that automatic transfer between exercises of local muscles and improved function of the global muscles occurs. They argue that it might be wise to include exercises for local muscles as well as global muscles in treatment strategies for PGP. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that women with persistent postpartum lumbopelvic pain have decreased muscle function in the trunk and hip muscles. Taking into account that several muscles of the anterior, posterior, and longitudinal sling are important for force closure, it would make sense to focus on all muscles responsible for force closure.

Based on this reasoning, we have compiled an exercise program including all 3 slings:

Arumugam et al. (2012) have investigated the effects of external pelvic compression. They found moderate evidence that pelvic belts can decrease laxity of the sacroiliac joint, change lumbopelvic kinematics, alter selective recruitment of stabilizing musculature, and reduce pain. So a pelvic belt might be a useful tool to use in patients with a positive active straight leg raise (ASLR).

Surgical Treatment

While conservative therapy shows decent results and should always be the first line of treatment, it might not show improvement in all patients. For those patients, further medical treatment options range from joint injections to radiofrequency neurotomy to joint fusion.

Simopoulos et al. (2015) investigated 14 different studies evaluating the effectiveness and safety of different medical interventions for SIJ pain. They found the following:

- Level II to III evidence for cooled radiofrequency neurotomy

- Level III or IV evidence for conventional radiofrequency neurotomy, intraarticular steroid injections, and periarticular injections with steroids or botulinum toxin

Pain is not simply a tissue-based stimulus-response. A study by Juch et al. (2017) confirms the effect of radiofrequency denervation of the SIJ in addition to exercise rehabilitation. No clinically important difference was observed in the primary outcome (pain intensity at 3 months after intervention) with the addition of radiofrequency denervation.

The last resort if conservative management and other medical options fail is minimally invasive joint fusion. Capobianco et al. (2015) set up a multi-center trial and found that women with PPGP experienced a significant improvement in pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months after surgery.

References

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Finally! How to Master Treating Spinal Conditions in Just 40 Hours Without Spending Years of Your Life and Thousands of Euros - Guaranteed!

What customers have to say about this course

- Shachaf Alexander19/07/24Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the spine

Interesting course packed with useful data and practical tools.

I highly recommend.Verena Fric25/11/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine GREAT COURSE ABOUT THE SPINE

great course, best overview about the different syndromes of the spine, very helpful and relevant for the work with patients - Peter Walsh01/09/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine 5 starsChristoph21/12/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Really a well done course, using the modern ways of teaching. Compliments! Sometimes for me you entered too much into details instead of touching more important chapters of Spine treatment like techniques for the treatment of muscles and fascias

- John09/10/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine EXCELLENT COURSE HIGHLY RECOMMEND

As a newly graduated physiotherapist i highly recommend this course just to know you are on the right track with your patients. the information presented is very clear and easy to follow as well as the great physiotherapy style videos. It makes learning actually fun , thanks guys for all your hard work. Well deserved.Alexander Bender06/09/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine During the corona crisis, I booked many online courses and webinars, but none were as entertaining and well thought out as PhysioTutors’ courses.

All units are well summarized, meaningfully broken down and easy to understand.

I am looking forward to the other courses.

Many greetings from Germany. - GHADEER05/01/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine VERY INFORMATIVE AND UPDATED

for anyone who is lost in handling spine cases, this course is very helpful.MICHAEL PROESMANS20/12/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine HIGHLY METHODICAL, WITH PLENTY OF SCIENTIFIC REFERENCE

Clear, structured and well researched course concerning most common pathologies of the spinal complex.

Plenty of informative modules, with detailed video-analysis.

If you’re looking for a course to study in your own time, with enough depth and scientific background, then you’ve found a very good one here.

Bang for buck, a great course. - BENOIT08/05/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine After finishing the Orthopedic course for Lower & Upper limbs, I was looking forward to begin this Spine specific course.

Really good overview about all spine pathologies from epidemiology to diagnosis & treatment which made me more confident to care for my future patients.

ANOTHER GREAT COURSE !

The courses are well detailed with lot of informations and videos.

For me these 2 courses are must to see to learn and update knowledge for most common pathologies in Physiotherapy.Nicolas Cardon27/04/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine This is a very interesting course !

We can find many informations about the main pathologies and their differential diagnosis and about objective and subjective exam. Videos are clear and well designed.

It’s a very well course for these who wish complete their Orthopedic Manual Therapy curriculum.

A French Physio’