Iliotibial Band Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment for Physios

Iliotibial Band Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment for Physios

Introduction

The literature handles different definitions of Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS), which is sometimes referred to as Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome, runner’s knee, or tractus iliotibialis syndrome (TITS). It is the most common running injury of the lateral side of the knee (Ellis et al. 2007) and the second most common overuse syndrome of the knee joint, after patellofemoral pain syndrome (Aderem et al. 2015).

There is an extensive body of research on the etiology of ITBS but no consistent definition of the underlying pathological mechanism of injury can be given. The most recent explanation is the combination of an impingement of the distal iliotibial tract at the lateral femoral epicondyle during repetitive flexion – specifically at around 30° of knee flexion. Additionally, compression of the highly innervated fat pad contributes to nociception (Baker et al. 2016, Taunton et al. 2002, Fredericson et al. 2000, van der Worp et al. 2012, Farrel et al. 2003, Ellis et al. 2007, Fairclough et al. 2006, Fairclough et al. 2007).

The question remains why the irritation occurs in the first place. Several studies investigated the role of intrinsic risk factors, such as glute strength and knee extensor/flexor strength, as well as extrinsic factors, such as the specific aspects of training (van der Worp et al. 2012).

Aderem et al (2015) report on modifiable and non-modifiable factors where the previously mentioned factors are modifiable and features such as anatomical leg length difference or a more prominent lateral femoral epicondyle are non-modifiable.

Epidemiology

ITBS rarely occurs in sedentary people and is most often seen in physically active individuals. The incidence and prevalence of running-related injuries (RRI) occurring during races or training varies between 25% and 65% of which ITBS is estimated to make up 5% – 14% of cases. Detailed and accurate reporting on the incidence is difficult as many studies do not only report on the incidence of ITBS and the characteristics of this group but report the incidence of all knee injuries (van der Worp et al, 2012).

LEVEL UP YOUR DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IN RUNNING RELATED HIP PAIN – FOR FREE!

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Picture & Examination

In the early phase of ITBS, patients typically report sharp burning lateral knee pain during running, which is elicited after a certain distance or time. Symptoms are felt mostly during the heel-strike and early flexion (20-30°), which is reduced or abolished once the activity is ceased (Orchard et al. 1996, Fredericson et al. 2000).

Conversely, these symptoms are elicited once the individual engages in running again.

If ITBS is not managed and persists over a longer period of time, it is likely that symptoms increase to a point where even ceasing the activity does not result in the abolishment of symptoms. The patient may then even experience familiar pain during ADLs such as walking, climbing stairs, or sitting for long periods of time with a flexed knee (Fredericson et al. 2000).

The Lindenberg classification grades ITBS into 4 categories:

- Pain onset after running, no limitation on distance and speed

- Pain onset during running, no limitation on distance and speed

- Pain onset during running, limitation on distance or speed

- Pain prohibits running

Physical Examination

Your anamnesis should tell you most of the required info to form the hypothesis of ITBS (signs & symptoms, provoking moments, location, onset, etc.). During your assessment you may assess for swelling around the lateral femoral epicondyle and tenderness upon palpation of the iliotibial tract 2-3cm proximal to the lateral joint line. Static and dynamic observation of the lower limb can help in identifying modifiable risk factors such as glute or quadriceps strength deficits. A simple assessment you can use is a single-leg squat and observe for the movement quality (femoral torsion, tibial torsion, valgus/varus, compensatory movement of the foot) as these may result in increased internal rotation or adductor moments in case of weak hip abductor/external rotator muscles. Running assessment on a treadmill can help in identifying crossover gait or unusually large strides, which increase the strain on the iliotibial band.

Furthermore, two special tests are described specifically for ITBS:

The second common test is Renne’s Test:

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

So before we discuss what you can do to rehab ITBS, let’s first look at what you shouldn’t do: As the ITB cannot lengthen, stretching is not a useful treatment option. Neither is foam rolling which – contrary to popular belief – does not release or break down adhesions. Given that ITBS is probably a compression injury, these 2 treatments might actually make matters worse.

So what should we do instead? When it comes to rehab for runners, we will have to focus on the following 3 main components, which were proposed by Willy & Meira (2016). These are:

- Peak loads, which will be addressed by heavy slow resistance training

- Energy storage & release, which we will train with plyometric exercises and

- Cumulative loads will be addressed by a graded return to running including running retraining.

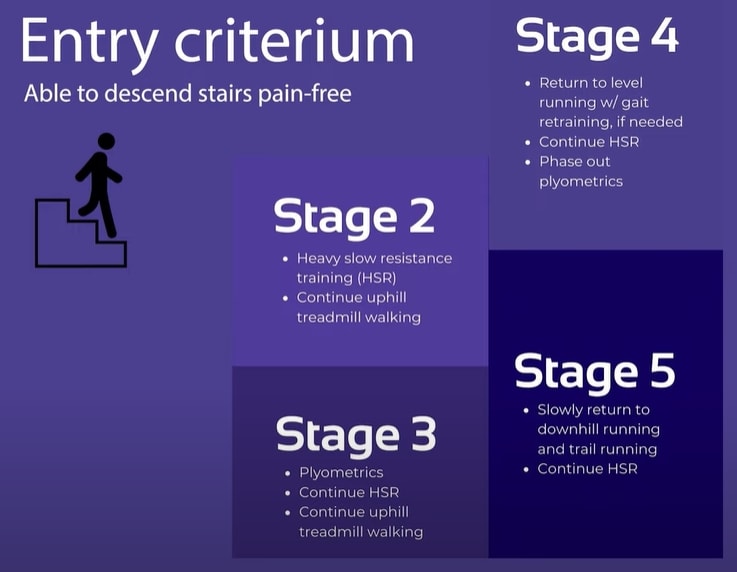

Our colleague Tom Goom has suggested the following 5 stage to progress ITB rehab in runners, which includes the 3 main components of rehab as well:

Stage 1 – The Pain Dominant Phase: Decrease irritability (without sacrificing capacity)

How do you know that your patient is in stage 1? These are patients that have often ceased running completely and who experience pain when descending stairs and with fast walking.

In this phase, the patient should reduce excessive overload by activities that further provoke the ITB. At the same time, we do not want a complete cessation of activities and keep their general activity level as high as possible.

In concrete, a patient should cease running – especially trail or downhill running – but switch over too fast treadmill walking with an inclination of around 8 to 10 degrees. If this is also not possible, the patient should explore if cycling with a low saddle or swimming are pain-free alternatives.

The following exercises are low-load options that focus on strengthening the hip abductors and extensors:

- Clamshells

- Side-lying abduction

- Thomas Exercise / ITB Excursion Exercise: 10x10s holds

Stage 2 – The Load Dominant Phase

The load dominant phase is entered as soon as the patient is able to descend stairs pain-free.

Stage 2: HSR training to address peak loads running

They then enter stage 2 which mainly focuses on heavy, slow resistance training. While uphill treadmill walking is continued, the exercises from stage 1 are further progressed:

- Side-lying abduction 🡪 Side planks

- Thomas Exercise 🡪 Single leg bridges

- Fire hydrants

- Split Squats (Training leg is the trailing leg, shift as much weight to the back leg)

- Side lunges against a resistance band

3 sets of 10-12 repetitions progressed to 4 sets of 6-8 with increased resistance/weight and near muscular failure on the last rep. These heavy-slow resistance exercises should be performed 3 times a week until a return to running is achieved in stage 5. The same is true for uphill treadmill walking which can be ceased as soon as running can be resumed.

Stage 3: Plyometrics to address energy storage and release during running

When rehabbing a patient with ITBS it’s important to realize that the ITB acts similar to a tendon in a way that it stores and releases energy during running as mentioned in a study by Eng et al. (2015). For this reason, we will have to train the ITB function to deal with energy storage and release activities without the cumulative load we get from running. The fact that the ITB works like a tendon should also make us wonder why many approaches are trying to decrease stiffness and lengthen it. If there is one thing we know of tendons is that they need to be stiff to be efficient as spring and lengthening – like in Achilles tendon ruptures – renders them inefficient. To confirm this A study by Friede et al. (2020) showed that physiotherapy improved outcomes in patients with ITBS and actually increased ITB stiffness by 14%. Examples of plyometric exercises progressed from easy to more advanced are:

Plyometrics Beginners

- Mini Squat jumps

- Reverse Lunge + Hop

- Lateral skaters (with bands or step)

- Tempo run with elastic bands

Plyometrics Advanced

- Split Jumps

- Squat jump to single–leg landing

- Single leg hopping forwards and backward

Stage 3 is used as a rather short (~1 week) bridge from stage 2 to stage 4

Stage 4: Return to level running + gait retraining

As soon as stage 4 is entered, the plyometric exercises are phased out in the second or third week.

Running should be re-introduced in a graded manner. To give you a concrete plan on how to build up running download our “From the Couch to 5K” running plan for free. This pdf is one of many useful documents from our running rehab online course.

A good idea is to gradually lower the inclination angle of the treadmill from 8-10 degrees to 5 degrees until the runner is able to run on level ground or outside again. There are a couple of biomechanical factors that can be targeted by mirror re-training. Be aware that gait modifications should be specific to the runner in front of you and don’t apply to every case:

- Increased step width: While cross-over gait usually puts more strain on the ITB, running with a wider gait reduces compression. You can train this by giving the patient cues like “Don’t cross over the line” after you have drawn a line with chalk in the middle of the treadmill.

- Increase the knee window: This means that there is space between the knees when you analyze their running pattern from a posterior view. A cue to achieve a bigger knee window could be to tell your patient “Don’t let your knees kiss” or you could put some tape on the outside of both knees and tell the patient to “push the markers apart”.

- If the patient presents with a pelvic drop also called the Trendelenburg sign, you could put markers on their iliac crest and cue them to “keep the markers level”.

- Increase cadence: Increase the cadence by about 5-10% which can be achieved by a metronome for example and reduces the peak load on the knee as well as peak hip adduction.

Running retraining is especially important as a study by Willy et al. (2012) showed that glute strengthening does change running mechanics. In the same study, they confirmed that mirror gait retraining on the other hand is effective for improving running mechanics.

Stage 5: Return to downhill running and trail running

In this last stage 5, the runner should gradually increase his running volume. Trail and downhill running can be gradually added on separate days before they are combined in a session.

Okay, so first of all a quick shout out to running experts Rich Willy, Tom Goom, and Benoy Mathew for valuable input for this post.

Would you like to learn more about Iliotibial band syndrome? Then check out the following resources:

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome – Facts or F(r)iction?

- Online Sports Conference 2022

- Foam Rolling – Sense & Non-Sense

- Running a Half-Marathon with ITB Pain

- Successful Return to Running Webinar

References

Illustration adapted from: http://www.bodyheal.com.au/blog/iliotibial-band-syndrome-symptoms-causes-treatment

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance

What customers have to say about this online course

- gustaf hübinette05/02/25A fantastic course A fantastic and comprehensive course that I feel has both broadened and deepened my knowledge of running-related injuries and their rehabilitation. The content maintains a clear and cohesive structure, firmly grounded in research. A big plus is that even after completing the course, you can revisit the material whenever you need to review certain areas.Simon20/01/25Good, but too much! It's of course a luxury problem. It delivers, absolutely. I know a lot more about running injuries now. But you need to review how much time it takes to finish this monster.

- Salih Kuzal30/12/24Running Rehab Salih Kuzal Een hele leuke uitgebreide cursus wat goed toepasbaar is in de dagelijkse praktijk. Heb er veel van geleerd!Sander Wierstra27/12/24Leerzame cursus Deze cursus heeft me inzicht gegeven om topatleten en sporters beter te begeleiden richting een duurzame herstel, ik raad deze cursus zeker aan!

- Jaime van der Lugt27/12/24Running Rehab 2.0 Well organised and clear set-up course to dive deeper into Running Rehab. Very extensive. Would definitely recommend it!Jasper Campfens24/12/24Top cursus Erg sterke cursus. Zeer uitgebreid wordt er ingegaan op alle meest voorkomende hardloopblessures. Van diagnose tot RTR.

- Carmen21/12/24Running Rehab Very good en clear course!Thorin21/12/24Sterke aanrader! Zeer uitgebreide cursus over een grote populatie binnen de bevolking. Elke kinesitherapeut zal hier veel uit bijleren, of hij nu zelf aan lopen doet of niet! Gestructureerde cursus bestaande uit Evidence-Based teksten en video's. Duidelijke toepassing van de theorie terug te vinden in de video's.

- Ivo Rigter03/12/24Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance Bedankt voor de zeer uitgebreide en informatieve cursusEllen Oosting27/11/24Veel geleerd! Veel geleerd over blessures, behandeling, training en terugkeer naar sport. Afwisselende inhoud. Veel praktische tools. Punten ook snel bijgeschreven na afronding.

- Olivier19/11/24Goede cursus! Ik kan deze cursus alle fysiotherapeuten aanraden!Joas de Bijl07/11/24Fijne cursus Goede cursus waar wetenschap en klinische ervaring in terug komt. Leuke video’s die wat mij betreft goed aansluiten op de praktijk!

- Koen24/10/24Leerzame Cursus Een cursus die een absolute bijdrage levert voor therapeuten die veel patiënten zien met hardloopblessures.

Vooral de praktische tips en de opbouw na een blessure zijn erg bruikbaar en toepasbaar in een eerste lijn praktijk.

Tevens zijn de evidence based artikelen een mooie toevoeging op de kennis die al wordt gegeven.Tim14/10/24Great course Learned a lot about running injuries. So much more structure in assessing and treating all lower limb injuries. - Maria Kramer14/10/24Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance Goede cursus voor therapeuten die veel hardloopblessures behandelen en hier meer over willen weten. Veel evidence based informatie en praktische tips voor de opbouw na een blessure.Emin Yildiz26/08/24Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance Leerzaam, uitleg en inhoud van top kwaliteit!

- Daniel Deyhle02/02/24Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance A VERY DETAILED COURSE

Really nice! Lot´s of high quality content! I learned so much. Thank you!Jarne Standaert18/04/23Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance Dit is een uitstekende cursus voor therapeuten die patiënten met loopblessures gerichter en efficiënter willen behandelen. Je krijgt enerzijds een uitgebreid overzicht van welke loopgerelateerde blessures zich vaak voordoen. Anderzijds krijg je een goed onderzoekskader om de tekorten bij je patiënten op te sporen en dus ook gerichter te behandelen. De cursus is heel duidelijk. Je krijgt ook een goed beeld van welke oefentherapie je best toepast in een bepaald stadium van een bepaalde pathologie - Hannah Yelin09/04/23Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance A great course that gives you a comprehensive and detailed knowledge of various running complaints. The content is evidence based and the literature is attached. It is very well taught how to transfer the evidence into everyday practice. I highly recommend this course to all physios who work with runners.

Thank you for a great course!Ruba Al Barghouthi23/10/22Running Rehab: From Pain to Performance Very informative course. Highly recommended for every MSK Physiotherapist and any other health care providers who deal with runners.