The Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy in Lumbar Surgery

Introduction

The ongoing increase in lumbar spine surgeries over the past decades raises the need for careful patient selection and targeting, especially since about one-third of patients have poor outcomes following surgery. Psychosocial factors are increasingly recognized as important prognostic factors that should be assessed preoperatively, as they predict worse outcomes. Patients with increased preoperative depression scores still show worse disease severity scores postoperatively (Javeed et al., 2024). On the other hand, patients with positive impressions of their own health do better following surgery (Gaudin et al. 2017). As not all outcomes following lumbar spine surgery yield sufficient success rates, and as surgery is irreversible, careful selection of patients who are likely to respond is advocated. Pain self-efficacy has been shown to be a protective factor in chronic pain management. But as previous studies have only investigated the role of pain self-efficacy on psychosocial factors in isolation, this study examined the role of pain self-efficacy as a moderator in the relationship between multiple psychosocial factors and health-related quality of life.

Methods

This cross-sectional study investigated the moderating role of pain self-efficacy in lumbar surgery on the association of psychosocial factors with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients awaiting lumbar spine surgery. The study was conducted between April 2021 and March 2023 in Japan. Importantly, all data collection occurred on the day before surgery, and no measurements were taken postoperatively.

Eligible candidates were adults of at least 20 years, who were scheduled for lumbar spinal fusion or decompression surgery for treating lumbar spinal stenosis or lumbar disc herniation. Patients with lumbar vertebral fractures, dislocation, tumors, prior lumbar spine surgery, or neurological conditions were excluded.

All participants received standard pain management, which typically included NSAIDs, acetaminophen, muscle relaxants, pregabalin or gabapentin (for neuropathic symptoms), and occasionally tramadol for severe pain.

Demographic variables like age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and clinical data regarding the diagnosis were extracted from the medical records. The following measurements were obtained on the day before surgery:

- The EuroQol 5-dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire was completed to capture HRQOL. This tool has 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), each rated on a 3-level scale (no problems, some problems, extreme problems). Scores range from 0 (worst imaginable health status) to 100 (best imaginable health status).

- Pain intensity was measured using the 4-item pain intensity measure (P4). This scale assesses pain intensity in the morning, afternoon, evening, and with activity over the past 2 days, using an 11-point numeric rating scale (0=no pain, 10=pain as bad as it can be) for each item. Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater pain intensity.

- Pain self-efficacy was assessed using the 2-item shortened Japanese version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ). Each item is rated on a 7-point scale (0=not at all confident, 6=completely confident), yielding a total score from 0 to 12. Higher scores indicate greater pain self-efficacy.

- Anxiety and depression were evaluated using the Japanese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), consisting of two 7-item subscales: HADS-A (anxiety) and HADS-D (depression). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (0-3), with total subscale scores from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher severity of anxiety and depression.

- Fear of movement (kinesiophobia) was measured using the 11-item shortened Japanese version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). Each item is rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 11 to 44, with higher scores reflecting higher fear of movement.

- Pain catastrophizing was assessed using the 6-item shortened Japanese version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time), yielding a total score from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of pain catastrophizing.

- Central sensitization-related symptoms were assessed using the 9-item shortened Japanese version of the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI). Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (none) to 4 (always), with a total score from 0 to 36, again with higher score indicating increased severity of central sensitization-related symptoms.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses were used to examine direct associations and moderating effects of pain self-efficacy on HRQOL (with the EQ-5D as dependent variable). Demographic variables and pain intensity were entered as covariates. Psychosocial factors (HADS-A, HADS-D, TSK, PCS, CSI, and PSEQ) were incorporated. Interactions with pain self-efficacy were assessed.

Results

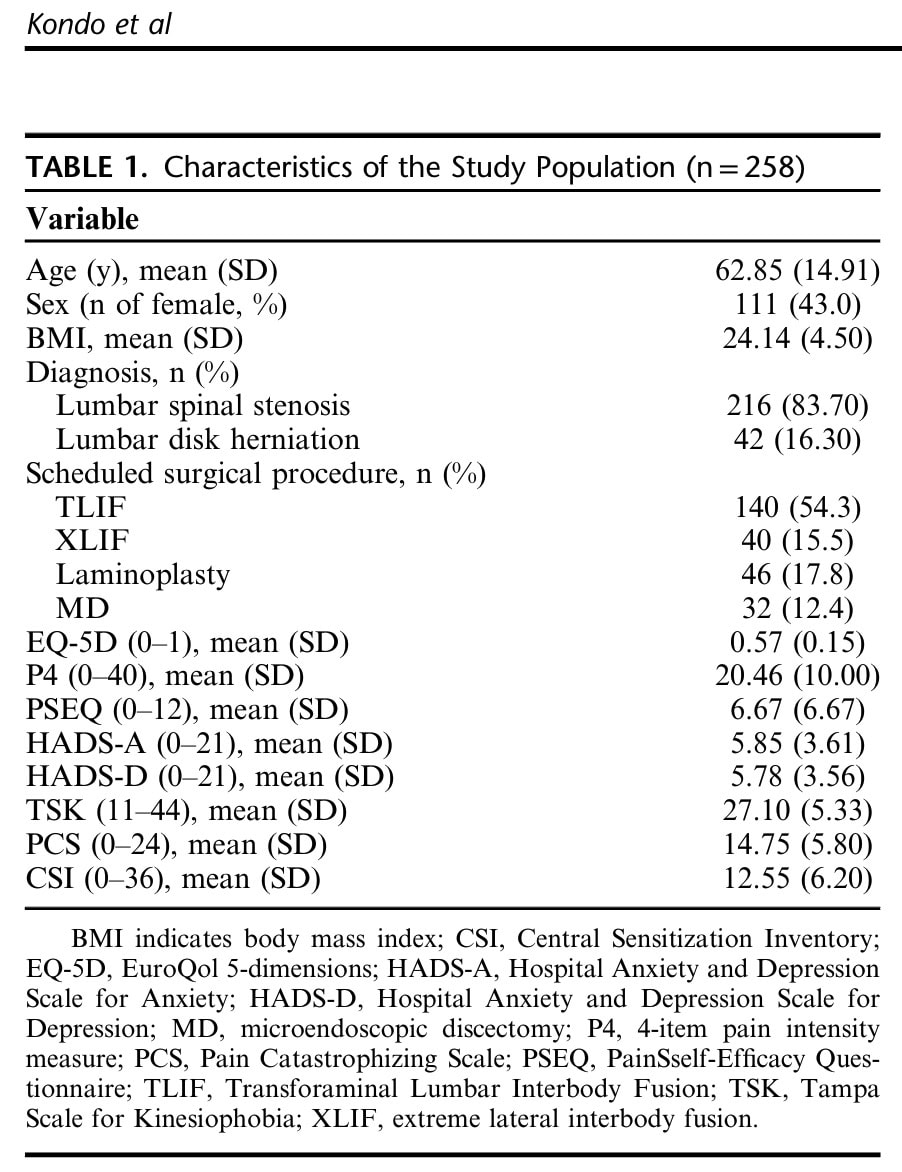

A total of 258 participants were included in the final analysis, of whom 111 were female and 147 were male. Their mean age was 62 years, and they had an average BMI of 24.14 (SD: 4.5) kg/m2. In more than 4 out of 5 participants, lumbar spinal stenosis was the main diagnosis (83.7%). Only 16.3% of participants were diagnosed with lumbar disc herniation.

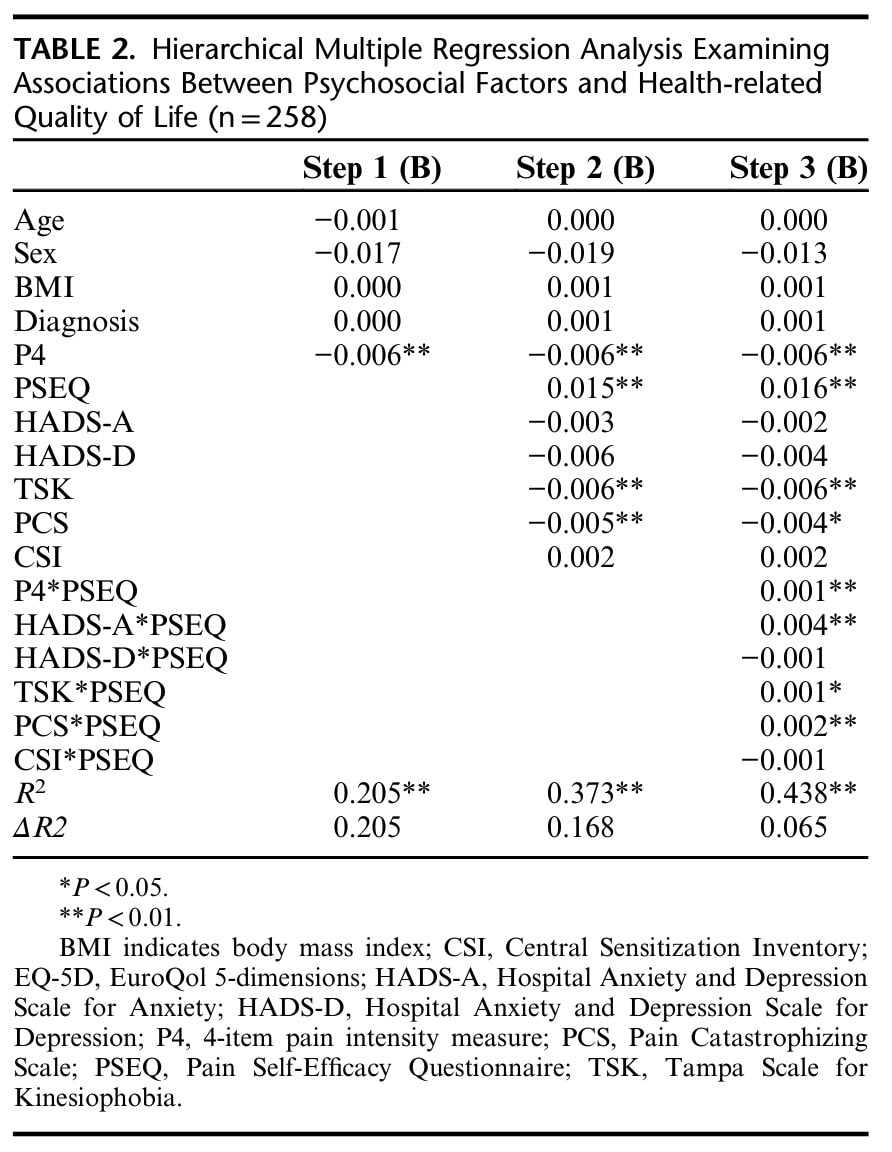

In Step 1, demographic factors and pain intensity were introduced in the regression analysis, revealing that these variables explained 20.5% of the variance in HRQOL. Pain intensity was significantly related to HRQOL. In Step 2, the psychosocial factors were introduced in the regression analysis, revealing that pain self-efficacy, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing were significantly related to HRQOL. These variables added another 16.8% of the variance in HRQOL. In Step 3, the interactions between pain self-efficacy and the other variables were explored. This step accounted for an additional 6.5% of the variance in HRQOL. The final model, therefore, explained 43.8% of the variance in HRQOL.

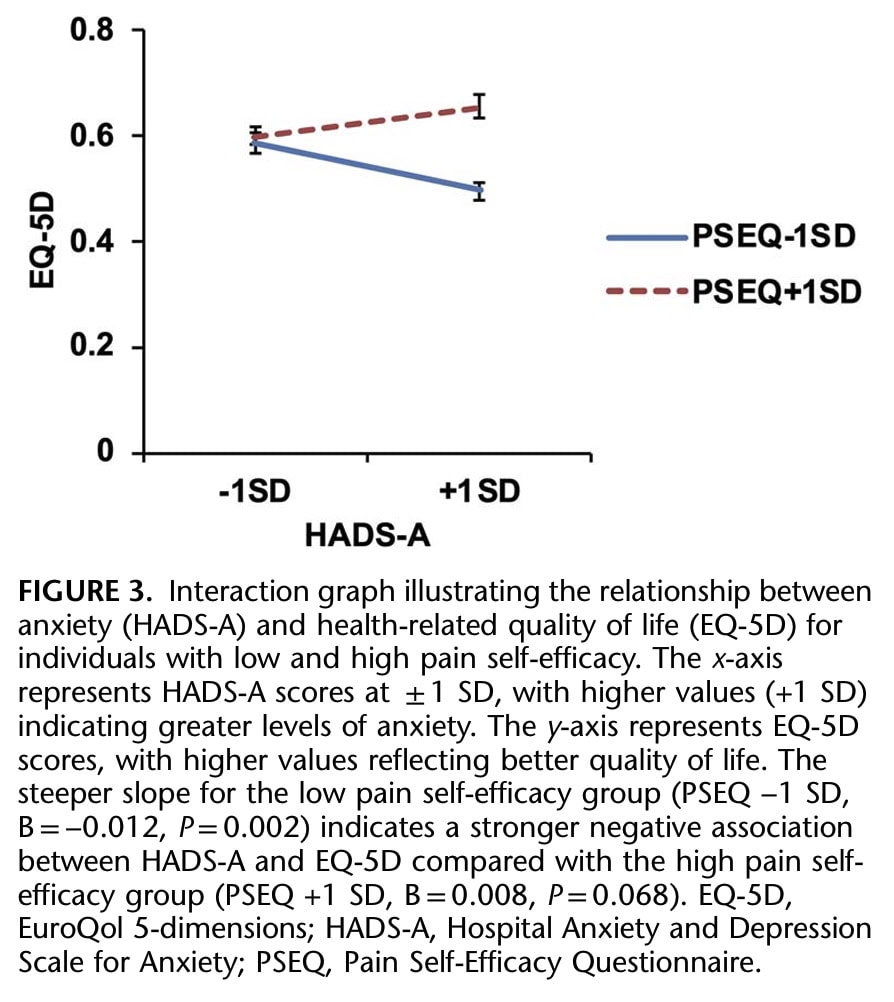

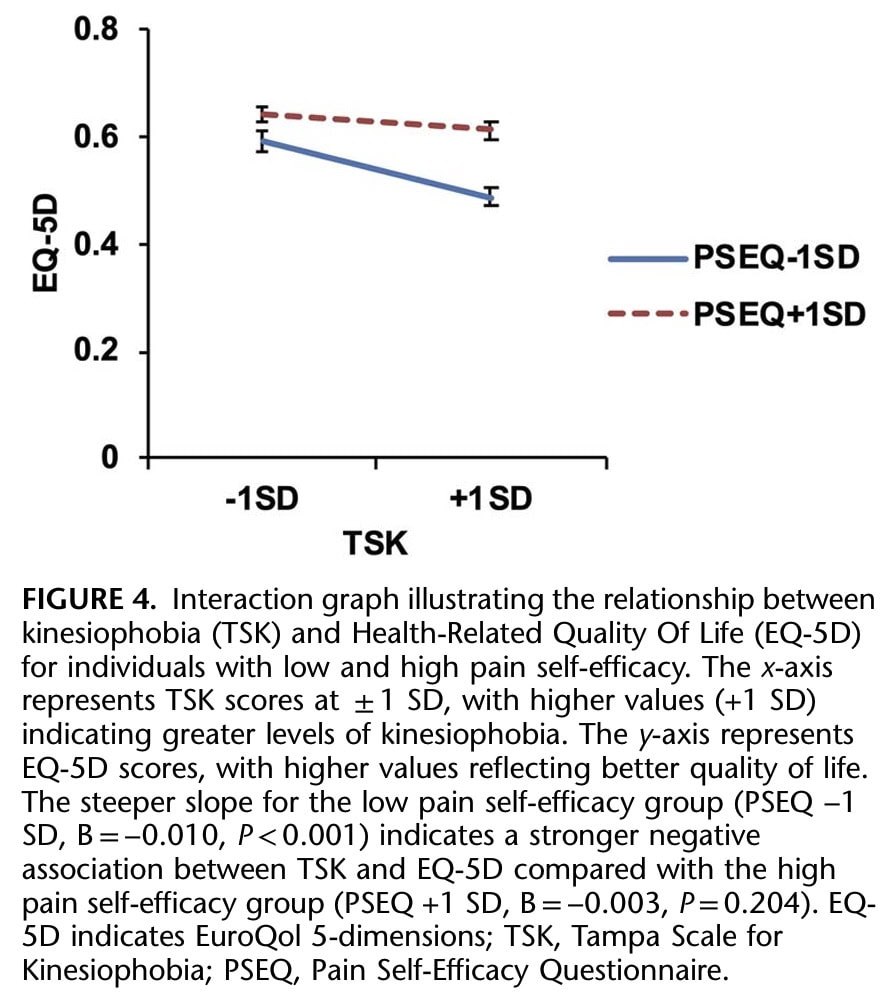

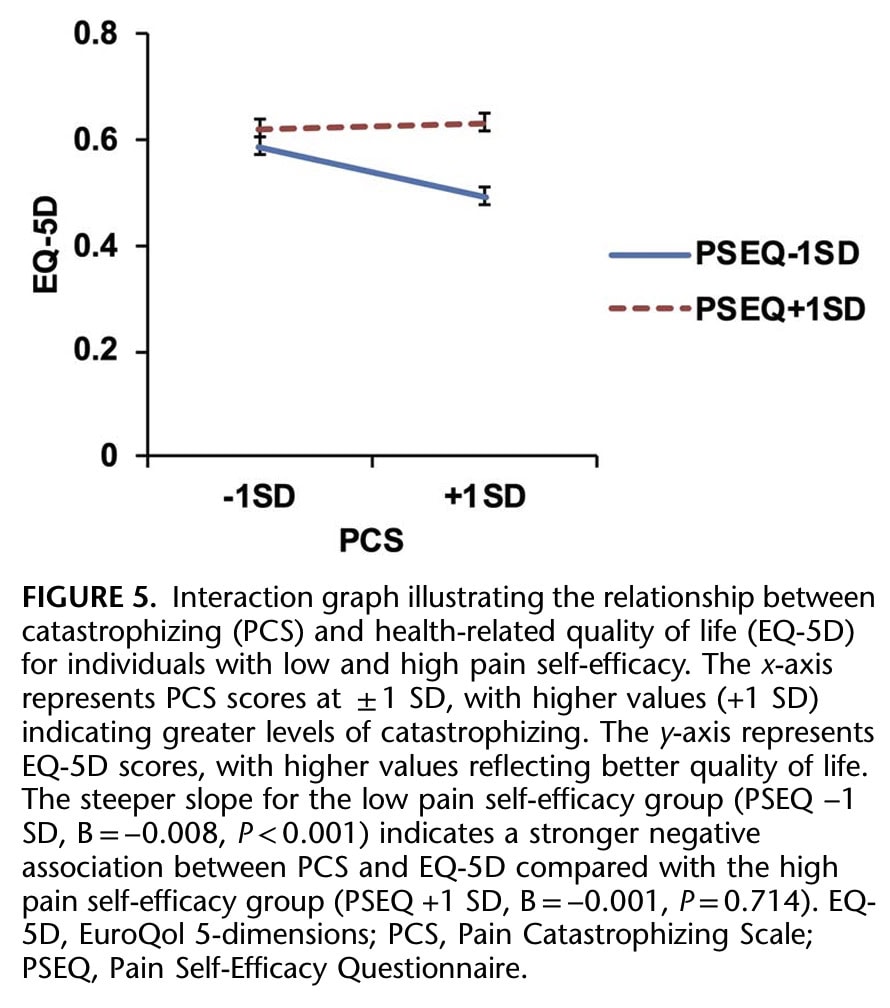

Significant interactions between pain self-efficacy and pain intensity, anxiety, kinesiophobia, and catastrophizing were found. Therefore, the moderating role of pain self-efficacy in lumbar surgery-scheduled patients was shown.

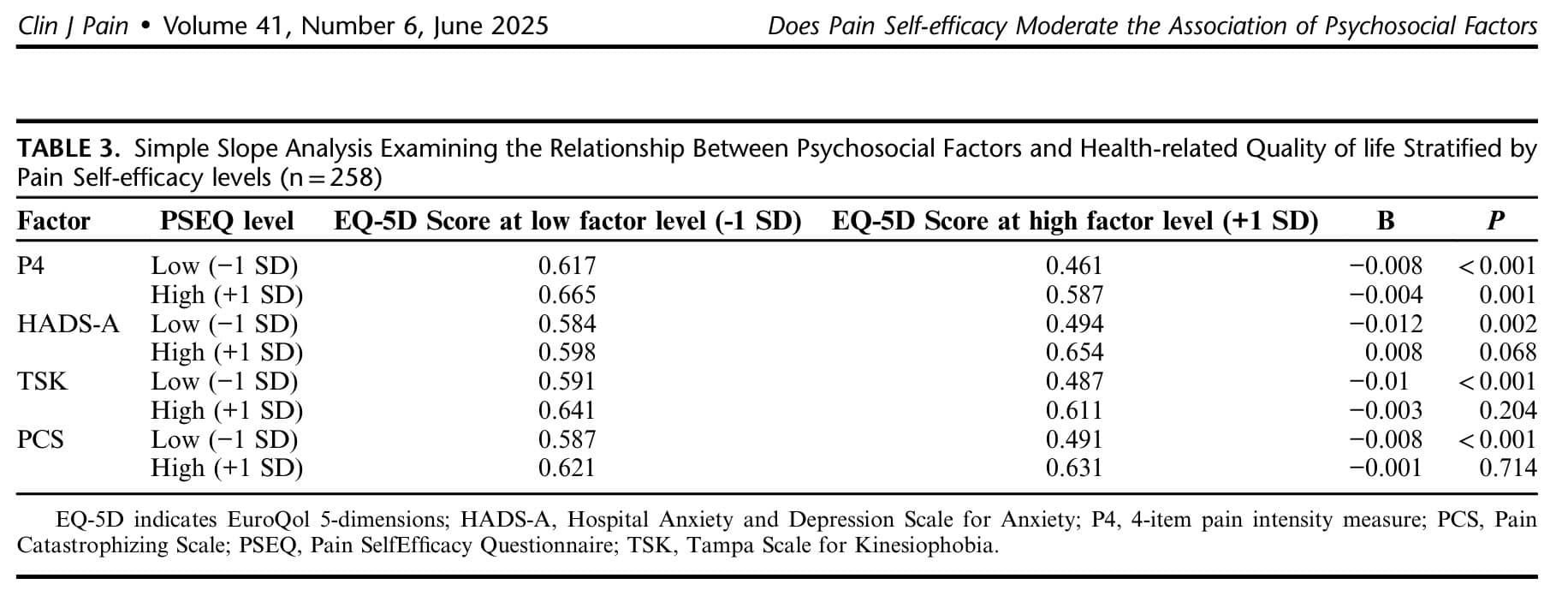

Using simple slope analyses, the authors examined the relationship between the significant psychosocial factors and HRQOL, stratified by the pain self-efficacy levels. The PSEQ score was divided into high and low levels of self-efficacy.

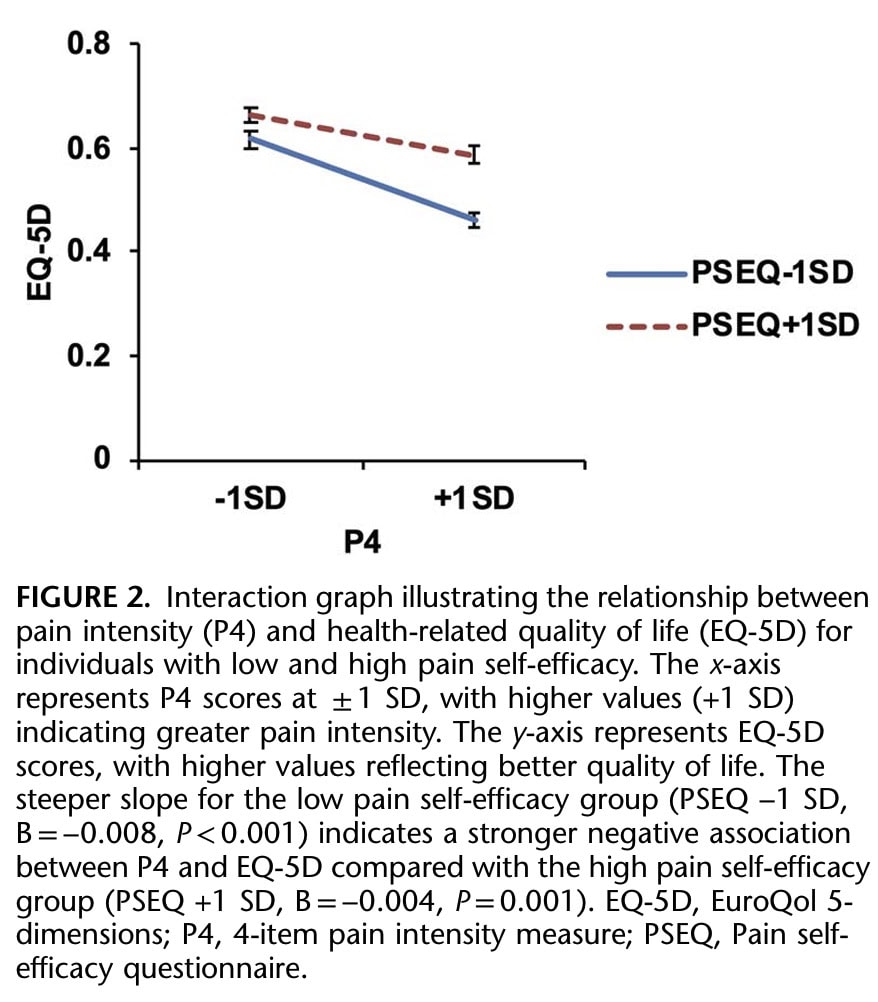

Pain Intensity: The negative association with HRQOL was stronger in the low pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.008, P<0.001) compared to the high pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.004, P=0.001).

Anxiety: The negative association with HRQOL was significant in the low pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.012, P=0.002), but not significant in the high pain self-efficacy group (B=0.008, P=0.068).

Fear of Movement: The negative association with HRQOL was significant in the low pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.010, P<0.001), but not significant in the high pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.003, P=0.204).

Pain Catastrophizing: The negative association with HRQOL was significant in the low pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.008, P<0.001), but not significant in the high pain self-efficacy group (B= -0.001, P=0.714).

Questions and thoughts

The article did not provide a detailed description of the participants’ pain characteristics. They stated that patients with lumbar spinal stenosis or lumbar disc herniation who were scheduled for spine fusion surgery or decompression procedures were included. But further than that, no pain characteristics were mentioned. As symptoms may vary a lot, from subtle paresthesia and cramping to severe loss of strength, treatments have to be chosen in light of the presenting symptoms. Someone rapidly progressing to worsening neurological symptoms would likely benefit more from emergency surgery, while someone with mild cramping of the legs could benefit from a nonsurgical approach.

Furthermore, both patients with spinal stenosis and lumbar discal herniations were included. While these pathologies might lead to a shared symptomatology, the underlying pathophysiology is different. Lumbar spinal stenosis develops gradually, with symptoms typically increasing over time, and can be seen as a slow-onset condition. On the other hand, lumbar disc herniations can develop gradually over time as well, but sometimes a more acute onset of disc herniations occurs following a sudden injury or trauma. These different underlying pathomechanisms may also have played a huge role in the associated psychosocial factors. For example, someone with acute-onset symptoms due to an acute lumbar disc herniation might have higher levels of anxiety, pain, kinesiophobia, and catastrophizing than someone who faces a relatively slow progression of symptoms over time. The latter person might have learned that certain movements might increase pain, but do not have to be avoided or feared. Unfortunately, differences between the patient groups were not explored. We must also highlight that more than 80% of participants were affected by spinal stenosis.

The collection of the psychosocial measurements on the day before undergoing lumbar spine surgery may have had implications for the psychosocial factors themselves. I would suppose that anxiety levels might be increased in general on the day before having such a procedure.

Talk nerdy to me

A potentially important limitation is the use of the shortened 2-item PSEQ for capturing self-efficacy in lumbar surgery patients. Although the authors indicated that this shortened version achieved acceptable internal consistency, they also admit that it might not fully capture the multidimensional nature of pain self-efficacy. With pain self-efficacy being the subject of the study, this poses an important threat to the conclusions of the study.

The researchers in this study checked for multicollinearity and found that the relationships between their variables were not too strong (correlations were between 0.10 and 0.65, and VIFs were between 1.0 and 3.3). This means that multicollinearity was not a significant threat to the article’s findings, and they could be reasonably confident in the results of their statistical analysis regarding the associations and the moderating effect of pain self-efficacy in lumbar surgery-scheduled patients.

Take-home messages

Higher levels of pain self-efficacy in lumbar surgery-scheduled patients showed a direct positive association with health-related quality of life. Higher pain self-efficacy attenuates negative relationships between pain intensity, anxiety, kinesiophobia, and catastrophizing with HRQOL. This indicates that in this population of patients scheduled for spinal surgery, higher preoperative levels of self-efficacy are associated with a more favorable psychosocial profile.

When patients have a stronger belief in their ability to manage their pain, the bad effects of things like intense pain, feeling anxious, being afraid to move, and pain catastrophizing are less strong. Think of pain self-efficacy as a kind of shield. When this shield is stronger (higher self-efficacy), it doesn’t completely get rid of the negative things (like high pain or anxiety), but it makes their impact less severe on the patient’s quality of life before surgery. The study showed that this stronger belief in managing pain weakens the negative associations between those difficult feelings and experiences and how well the patient feels overall.

Important to remember is that all measurements were obtained on the day before surgery, therefore representing a snapshot of the participants’ statuses. These do not reflect any change in postoperative outcomes. That is the greatest limitation of a cross-sectional study. Nevertheless, the findings from this study indicate that stronger negative associations between psychosocial factors and HRQOL appear in patients with low self-efficacy, and can steer future research to understand how pain self-efficacy in lumbar surgery patients can influence postoperative surgical outcomes over time.

Reference

DISCOVER FASCIA FROM ITS HISTORY TO ITS VARIOUS FUNCTIONS

Enjoy this free 3x 10min Video Series with Renowned Anatomist Karl Jacobs who will take you on a trip into the world of Fascia