Part 2: Clinical Pearls and Advice From a Young PT to Even Younger PTs

We hope you enjoyed last week’s blog article about “Clinical Pearls and Advice from a young PT to even younger PTs” from Dr. Jarod Hall. If you did, check out the second part of his article!

You can find Jarod’s Blog on: http://drjarodhalldpt.blogspot.com

After a little brainstorming and time to ponder on the meaning of life, I came to the conclusion that I left out a few good bits of advice in my first post. I know what you’re thinking… “the first one wasn’t half bad, but things always go downhill when they make a sequel!”

Hopefully, that isn’t the case! The following is a short update to the list of information I wish I knew/understood when I started out. My goal is to take the information I’ve learned from the brilliant minds in PT and pass it down without the years of struggle it usually takes in-between, so the profession can continue to push further and further forward to gain the respect it deserves. So, without further ado, I present to you part two of my list:

- I’ve found that it can be very powerful to ask your patient what THEY think they need to get better. Sometimes they will say “that’s what I’m here to see you for!” which leaves the floor open for you to pull out your best game as a clinician. However, sometimes they will tell you that “I feel weak here and I think I need X” or “if I could just figure out how to work on Y I know that would help me out”. Then you have a wonderful situation of being able to give the patient a treatment you are positive they have bought into while simultaneously selling them on other interventions that you know may be physiologically what would benefit them most.

- It just isn’t possible for us to be super specific with our mobilizations and manipulations like you were taught in school so stop worrying about PPIVMs and PAIVMs. Research has shown that experienced therapists can’t even accurately palpate the same level with acceptable reliability, and manipulation techniques have been shown to disperse force over several vertebral levels as well as cavitate on both sides. The effects of manual therapy are most likely much more generalized than they are specific based on current research. I’ve written a post on this topic here. So, as my most recent student said “Damn, I’m sure glad you told me this, because now I know I’m not crazy for feeling like the worst physical therapist ever when we were asked to palpate all of this in class and I couldn’t!!!”

- Use as much body contact as you possibly can with your patients while doing manual techniques such as PROM on their shoulders. Too often I see therapists, especially young ones, holding a patient’s arm like it’s the crank on old school water well instead of getting in close and making them feel safe with their arm in your hands.

What’s the point in even doing PROM if the patient is guarding so bad you can’t even get close to their available end range because they aren’t comfortable and are guarding. Use as many points of contact as you can to support them and allow them to fully relax.

- It would probably be a good idea to stop spending so much time manual muscle testing every single motion on every patient that walks through your door. I know you probably had an entire class on goniometry and MMT, but in reality, it wastes time you could spend evaluating the way a patient actually moves, building your therapeutic alliance, or educating them on their condition. Are there times in which MMT is a good idea? Sure, but on the whole, it’s way over sold….and incredibly subjective after a 3+ anyway.

- Try using extrinsic cueing vs intrinsic cueing. Instead of telling a patient with hip adduction and femoral internal rotation during squatting/landing to keep their knees in line try telling them to screw their feet into the floor (engage external rotation at the hips) or split an imaginary line in the floor underneath them as they squat. A trick that I’ve used several times that works well is to use a mirror and dots on a patient’s knees for extrinsic visual feedback. Instruct the patient to keep the dots from falling in towards each other. Or in the case of a 16 y/o cheerleader with PFPS and significant valgus collapse on her R side during landing with her cheer jumps, you could use smiley faces on her knees and tell her to not let them look at each other when she lands (true story and worked great).

- Learn what a nocebo is, and try your hardest to avoid creating a situation in which there is a nocebo effect. Stop using the words like herniated, bulging, punched, worn out, degenerated, etc, and replace them with irritated, sensitive, and threatened by “x” direction instead. These replacement words give the impression of a transient problem to the patient. A problem that CAN and WILL get better

- Stop telling people their core is unstable… Odds are it’s not… Core stabilization has been shown to be no better than general exercise for low back pain in a plethora of studies. Not to mention the potential nocebo effect of patients picturing a weak, wobbly, wimpy spine. Try instead thinking about exercises for low back pain in categories of those that decrease threat perception (repetitive motions, nerve glides, positioning), those that explore new movements (prone on elbows, cat-camel, pelvic tilts, etc), and those that get the patient moving and load/challenge the system (squats, deadlifts, reverse hyper, cable resisted rotations, etc).

- Fascia isn’t magical- it’s an interesting tissue and most likely plays a role in pain/dysfunction occasionally, but it certainly is not the panacea that it has been made it out to be in recent years…. Oh yeah, and you can’t release it like you’ve been so adamantly taught. Even the “father of fascia” has grown weary of all the hype and marketing ploys surrounding it.

“I am so over the word ‘fascia’. I have touted it for 40 years — I was even called the ‘Father of Fascia’ the other day in New York (it was meant kindly, but…) — now that ‘fascia’ has become a buzzword and is being used for everything and anything, I am pulling back from it in top-speed reverse. Fascia is important, of course, and folks need to understand its implications for biomechanics, but it is not a panacea, the answer to all questions, and it doesn’t do half the things even some of my friends say it does.”

-Tom Meyers (father of fascia)

- If a muscle feels really “tight” it is rarely actually the muscle that has limited mobility. Most often this feeling of tightness is due only to a perception the central nervous system has based on input from the periphery. It could be muscle weakness, decreased neural mobility, or protective guarding based on perception of threat such as joint hypermobility. Decrease the threat or strengthen the tissue and you decrease the perceived tightness. I regularly work with professional ballet dancers, who let me assure you are not tight in any way. However, they regularly come to me with complaints of hip, ankle, calf, neck, etc tightness. They report that they feel tight and restricted in their movements, yet they can move beautifully through ranges of motion most of us could never dream of. Neural mobilization techniques as well as positioning a muscle in a slacked position with a firm, but not painful, pressure usually work wonders to decrease the perceived threat and “tightness” that these dancers come to me for.

- The number one thing you can do for your injured runner patient is to get them on a well-rounded strengthening program….period…a stronger system can sustain more force with less breakdown.

- For runners with chronic problems such as medial tibial stress syndrome or PFPS (number one and two running injuries) simply cueing to shorten their stride length and increase cadence can make a huge impact. This will get their foot strike more directly underneath them and help to decrease ground reaction forces distally and increase workload proximally to the bigger stronger muscles. Shoot for a cadence higher than 160bpm.

- Forefoot striking usually increases force distribution to the foot, ankle, and calf while mid to rearfoot strike patterns transmit more forces to the knee and hip. Changing strike patterns occasionally can be good for allowing different tissues to “rest”.

- Patient-reported comfort is currently the best advice we can give regarding shoe choice for decreasing running-related injuries

- Mündermann A, Stefanyshyn DJ, Nigg BM. Relationship between footwear comfort of shoe inserts and anthropometric and sensory factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1939-45.

- “Shoe inserts of different shape and material that are comfortable are able to decrease injury frequency. The results of this study showed that subject specific characteristics influence comfort perception of shoe inserts.”

- Ryan MB, Valiant GA, Mcdonald K, Taunton JE. The effect of three different levels of footwear stability on pain outcomes in women runners: a randomised control trial. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(9):715-21.

- “The findings of this study suggest that our current approach of prescribing in-shoe pronation control systems on the basis of foot type is overly simplistic and potentially injurious.”

- Knapik JJ, Trone DW, Swedler DI, et al. Injury reduction effectiveness of assigning running shoes based on plantar shape in Marine Corps basic training. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1759-67.

- “This prospective study demonstrated that assigning shoes based on the shape of the plantar foot surface had little influence on injuries even after considering other injury risk factors.”

- Nielsen RO, Buist I, Parner ET, et al. Foot pronation is not associated with increased injury risk in novice runners wearing a neutral shoe: a 1-year prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(6):440-7.

- “The results of the present study contradict the widespread belief that moderate foot pronation is associated with an increased risk of injury among novice runners taking up running in a neutral running shoe.”

- In addition, the incidence-rate difference/1000 km of running, revealed that pronators had a significantly lower number of injuries/1000 km of running of -0.37 (-0.03 to -0.70), p=0.03 than neutrals.

- Based on current research those who “over pronate” while they run actually have a lower risk of running-related injuries….yes you read that right. See the above study in #12

- If you are interested in working with runners, learn who Chris Johnson and Tom Goom are and follow them ASAP. Zeren PT and the runningphysio.

- Explain pain to a patient in terms of a home alarm system. The alarm goes off if it senses danger, just as the brain produces pain in the event it perceives a threat. During persistent pain, the trigger on the alarm system can become very easy to trigger. Instead of someone needing to break a window to set the alarm off, the wind only needs to blow on the grass in the front yard. Just the same, instead of tissue damage occurring or something physically being “wrong” to cause pain, the smallest movements can set off the alarm system and cause one to unnecessarily experience pain. This analogy tends to be a great ice breaker for talking deeper about pain sciences with patients.

- To take the alarm system analogy a step further, it can be used to explain spreading pain or pain in other locations of the body. If you were out of town and your house alarm went off and you weren’t there to turn it off, it’s likely that it would end up waking your neighbors. Similarly, if the alarm system in the body is consistently ringing, it is likely that you could “wake your neighbors” and begin to experience pain in a wider area than the original area, or even in old injury areas that the brain has previously developed a neurotag to elicit pain.

- Explain whiplash injuries to patients as several small ankle sprains in their necks. Nothing super scary to worry about. Most patients have had an ankle sprain and healed just fine from it with no residual pain. Confidence and reassurance of improvement are more important than anything you can do early on for a patient after a whiplash injury.

- Try EVERYTHING you possibly can to get a patient out of pain within 3 months of their whiplash injury as those that have pain at three months almost always still have pain at 2 years…long after tissue has healed. Research shows that between 30-40% of patients with whiplash injuries progress into persistent pain. These people need our help and DEFINITELY need pain science education because you can be assured that their nervous systems are wound up.

- Based on the current evidence “Trigger points” may or may not (much more likely not…at least in the traditional definition) exist so stop explaining to your patients that they all have a million trigger points. Even the originators, Travell and Simons couldn’t agree on trigger point location with accuracy closer than a 3.3-6.6cm inter-rater error. I’m not blatantly saying there is no such thing as a trigger point right now, but I am saying that if there is, it isn’t quite so clear-cut as the basic explanations we have been taught. If it does exist, it likely has much more to do with some sort of PNS and/or CNS sensitization due to threat perception that leads to local neurophysiological changes in a certain grouping of peripheral nerves. Therefore, IF (and this is a big if) needling works beyond a strong placebo, specific needle placement into a trigger point is probably not necessary. If there are effects of needling, they are likely to be much more about a global change in the nervous system than a localized neuromuscular junction. (This is a personal opinion based on my current understanding of the literature. Feel free to disagree!)

- Challenge your patients, especially your older patients. Don’t fall into the yellow theraband trap! Their systems can still adapt and they might surprise you with what they can do. Better yet, they may surprise themselves!

- If you want to make a name in your community be different. Don’t be the same old tired PT that goes on autopilot. Be different by educating your patients. Education makes patients invest in their rehab, understand why they are doing what you have advised, and have a reason to do exercises. This leads to better improvements and more referrals. Word travels faster than you may think.

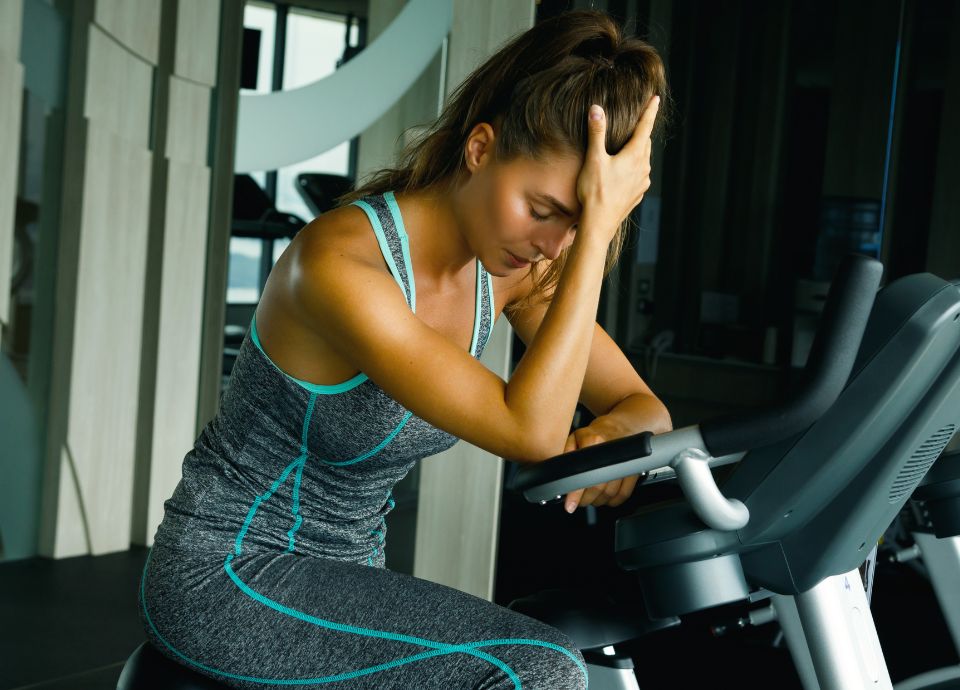

- This one may ruffle some feathers, but I strongly advise that you try your hardest to be healthy and in relatively good shape. Now I’m not talking about getting your Arnold on or anything, but research shows that it may take less than one second for individuals to make their first impression of you based on appearance. Interestingly, it also shows that it is surprisingly hard to change the immediate conclusion that has been drawn. It could be much easier for a patient to buy stock in the exercises you prescribe if it appears you know a thing or two about exercise and can easily perform whatever you are asking of them. This same premise is illustrated when everyone goes up to the jacked guy in the gym with phenomenal genetics for workout advice when he may or may not know half as much as the skinny guy in the corner working his butt off. It can be seen again when celebrities give health advice. Jenny McCarthy= ‘nuff said. Just because they look good and have the public eye on them people take what they say as gospel. Sadly, at the end of the day, you may be able to get through to your patients a little easier if you look the part.

- There is no list of inherently “bad” exercises. There are certain exercises that certain people should not perform due to injury, lack of mobility to complete said exercise, anatomic variance, or poor control during that exercise. But just because an exercise is bad for one or a few people doesn’t mean it is for everyone. The body is a dynamic system that steadily adapts to safe progressive overload over time. Deadlifts aren’t bad, squatting deep isn’t bad, the shoulder press isn’t bad, crunches aren’t evil, good mornings aren’t ripping your back in half, and knee extensions aren’t bad. They just need the requisite mobility, control, and progressive load.

- Stop making your patients do all sorts of exercises on an upside-down Bosu. It doesn’t increase EMG and has no specificity to carry over to anything “functional” in life. That old staple of specificity of training is still very important. Build strength and practice the actual skill to improve performance.

- When returning an athlete to sport after ACL reconstruction a single leg hop or Ybalance is not specific enough to do on its own. Athletes get tired and fatigue leads to breaking down in control. Fatigue the hell out of them to simulate a game situation and then test them for a better glimpse into how they may actually look after returning to sport.

- Don’t hang your hat on the VBI positional testing to make you feel comfortable and like you checked a box on a cervical patient. The VBI positional testing is mediocre at best and could actually stress the vertebral artery to a greater degree than HVLAT. A solid history of symptoms and cardiac history is much more important when screening the cervical spine before intervention.

- If you are interested in strength and conditioning learn who Brad Schoenfeld, Bret Contreras, Andrew Vigotsky, and Chris Beardsley are.

- If you are interested in nutrition find Alan Aragon, James Fell, and Spencer Nadolsky

- Finally, I strongly encourage you to learn to like good beer. Everyone knows all good PTs like craft beer…and you know, networking and stuff

Thanks again for reading! I would love to hear people’s feedback regarding these “pearls”.

-Jarod Hall, PT, DPT, CSCS

Jarod Hall

Jarod Hall, PT, DPT, OCS, CSCS

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.