Lateral Epicondylalgia / Tennis Elbow | Diagnosis & Treatment

Lateral Epicondylalgia / Tennis Elbow | Diagnosis & Treatment

Introduction & Epidemiology

Lateral Epidondylalgia is a frequent patient complaint, commonly referred to as tennis elbow (Pitzer et al. 2014). The association with the name tennis elbow for lateral epicondylalgia (LE) is due to the fact that the condition has long been associated with racquet sports and an estimated 10-50% of tennis players develop LE during their careers (Van Hoofwegen et al. 2010).

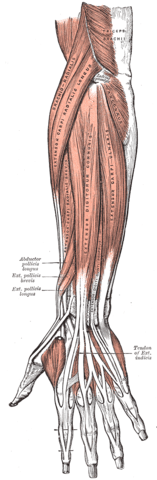

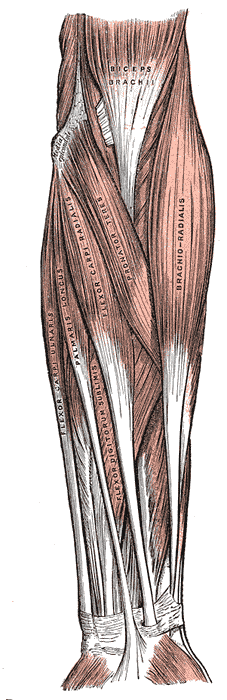

Tennis elbow is thought to result from overuse of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) muscle by repetitive microtrauma resulting in primary tendinosis of the ECRB, with or without the involvement of the extensor digitorum communis (De Smedt et al. 2007).

The term epicondylitis was questioned over time as histological studies have failed to show inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) in the affected tissue. These studies showed fibroblastic tissue and vascular invasion that lead to the term ‘tendinosis’. This rather defines a degenerative process characterized by an abundance of fibroblasts, vascular hyperplasia, and unstructured collagen (De Smedt et al. 2007).

Tichener et al. (2013) conducted a large case-control study with 4998 patients who were retrospectively screened for risk factors for the development of LE.

They found that rotator cuff pathology (OR 4.95), De Quervain’s disease (Or 2.48), carpal tunnel syndrome (OR 1.50), oral corticosteroid therapy (OR 1.68), and previous smoking (OR 1.20) were risk factors associated with the development of tennis elbow. Diabetes, current smoking, trigger finger, rheumatoid arthritis, alcohol intake, and obesity were not found to be associated with LE.

A study by Sanders et al. (2015) found that the annual incidence of LE decreased over time from 4.5 per 1000 people in 2000 to 2.4 per 1000 people in 2012 in the US population. They report a recurrence rate within two years is as high as 8.5% and remained constant over time. The proportion of surgically treated cases within two years tripled from 1.1% in 2000 to 3.2% after 2009. About 1 in 10 patients with persistent symptoms at six months required surgery.

In this study, the average age for the diagnosis was at 47 ±11 years of age with equal distribution amongst genders. The age group between 40 and 49 years thus has the highest incidence with 7.8 per 1000 in male patients and 10.2 per 1000 female patients.

The most commonly reported professions were office workers/secretaries followed by health care workers, mostly nurses. The right elbow was affected in 63% (vs. 25% left) with 12% of patients having both elbows affected. On the basis of this data, one might assume that the dominant arm is affected more often given the fact that an estimated 70-95% of the world’s population is right-handed (Holder et al. 2001)

Work restrictions were reported in 16% of patients with 4% missing 1-12 weeks of work.

In a study of the US military, incidence rates for LE were 2.98 per 1000 person-years (Wolf et al. 2010).

Another study by Leach et al. (1987) mentions that LE is 7-10 times more common than medial epicondylalgia.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Elbow pain is the presenting complaint in patients with epicondylalgia. While this pain can be acute in onset due to trauma or injury it is more likely to develop gradually.

Patients typically present with a history of repetitive gripping and loading of the forearm (Orchard et al. 2011). The pain is usually worse with activity and relieved by rest and may or may not radiate down the forearm along the wrist extensor (LE) muscles. On top of that, patients might experience weakness in the hand and difficulty carrying items (Pitzer et al. 2014).

Examination

For a thorough assessment and differential diagnosis, the cervical spine, shoulder, elbow, and wrist should be examined in both conditions. Next to excluding cervical radiculopathy of C5-C6 as a possible competing diagnosis, neck, and shoulder impairment have been found to be negative prognostic factors for recovery in lateral epicondylalgia (Smidt et al. 2006). Patients with lateral epicondylalgia present with tenderness at the origin of the ECRB, at or just distal to the lateral epicondyle. Although patients usually have a normal range of motion, some might have limitations of active elbow extension due to lateral elbow pain. Mild soft tissue swelling over the extensor origin is not uncommon and some patients have fullness in the anconeus triangle (Orchard et al. 2011).

Watch the videos below in order to learn how to conduct those tests:

WATCH TWO 100% FREE WEBINARS ON SHOULDER PAIN AND ULNA-SIDE WRIST PAIN

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

Although the course of LE is favorable with 89% of patients reporting improvement in pain after a 1-year follow-up, a randomized-controlled trial by Peterson et al. (2011) showed superior outcomes regarding pain with daily progressive exercise compared to a wait-and-see approach at three months follow-up. Currently, there is no common consensus as to which exercise modality is superior to another. Although isometric exercise generally seems to decrease pain in tendinopathy, Coombes et al. (2016) showed an increase in pain intensity after an acute bout of isometric exercise performed at an intensity above, but not below, the individual pain threshold. So while isometric exercise might still have a place in lateral Epicondylalgia rehab, exercising above the pain threshold might be less effective in the elbow compared to other body regions.

Another study by Peterson et al. (2014) compared a concentric vs. an eccentric daily home exercise program in patients with chronic LE. They found a faster decrease in pain and an increase in strength in the eccentric exercise group from two months onwards. However, both groups improved significantly regarding pain and strength and the crude difference between the groups was not significant at 12 months follow-up. For this reason, the authors conclude that both modes of exercise may be used in order to simplify the execution of the exercise, but stressing the eccentric work phase will probably provide an advantage.

The following exercises described by Kenas et al. (2015) can be included in a rehab program for lateral Epicondylalgia. We modified them in a way that the concentric portion of the exercise is included as well:

1)Wrist extensions:

- Have your patient sit with the forearm in pronation and supported on his thigh or any other surface.

- The elbow should be flexed to around 60 degrees.

- Then perform simple dumbbell curls in a controlled manner.

- If you want to isolate the eccentric part, you could simply help return the wrist to the top position with the uninvolved arm.

2) Wrist extension with a twist bar:

- With the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, the patient holds onto the bottom end of the twist-bar in maximum wrist extension

- With the uninvolved arm, the patient grabs the top of the twist bar with the palm facing away and maximally flexes the wrist, while the involved wrist is held in extension

- Then the patient brings his arms in front of the body with both elbows in extension and slowly lets the twist-bar to “untwist” by allowing the involved wrist to move into eccentric wrist extension.

- If you want to isolate the eccentric part of the exercise, move into the starting position and start over.

- If you want to include the concentric part of the exercise, have your patient keep the twist bar in front of his body.

- Then have him move the affected wrist into full flexion for the concentric portion.

- Afterward, the wrist is slowly allowed to move into extension again under eccentric contraction.

- A nice bonus of this exercise is that the uninvolved side is trained concentrically or isometrically in the latter modification as well.

3) Supination with an elastic band:

- Anchor an elastic band to a pole at elbow height.

- With a flexed elbow to 90 degrees, the patient holds on to the elastic band in maximal pronation and steps away from the anchor so that the band is under tension

- Then, the patient is asked to perform controlled supination for the concentric part and resists rotation of the forearm into pronation again for the eccentric part

- If you want to isolate the eccentric part only, start in full supination with little tension on the band and increase the tension by side-stepping away from the pole.

- Then rotate 180 degrees into the palms down position to allow eccentric Supination.

- Afterward, step back towards the anchor and return to the starting position.

4) Supination with a hammer or a dumbbell

- With the elbow flexed to 60 degrees, the patient grabs the distal end of a hammer handle with a neutral grip so that the weighted side is on top.

- Then, the forearm is slowly rotated through 90 degrees toward a palm-down position to allow eccentric Supination.

- If you want to isolate the eccentric portion of the exercise, return the hammer to the starting position with the uninvolved arm.

- If you want to include the concentric portion, try to supinate the forearm so that the hammer is returned to the starting position.

The authors recommend including one exercise for wrist extension and 1 exercise for wrist supination per session with 2 sets of 10 repetitions. Each repetition should be performed in a slow controlled manner. Sessions should be performed 3 times a week with a 24 to 48-hour rest period in between to allow for proper recovery and a positive net synthesis of collagen.

Similar to tendinopathies in other body regions good load management is key to rehabilitation. This means that the patient should temporarily avoid or reduce activities that aggravate the elbow pain. At the same time, the exercise program must be as close as possible to the tendon’s current capacity and progressed in the course of rehab in order to drive adaption. For this reason, we advise starting with a training volume that the patient can just tolerate in a pain-free manner and closely observing the patient’s 24-hour reaction to exercise. If there is no pain aggravation beyond the 24-hour mark after exercise, the training volume can be increased gradually by adding repetitions, sets, or intensity in the form of increased resistance.

Do you want to learn more about elbow conditions? Then check out our blog articles and research reviews:

- Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy Rehab Case Study

- Low-Load Resistance Blood Flow Restriction vs. Sham for Tennis Elbow

- Adding Strengthening Exercises to a Multimodal Treatment Program for Lateral Epidcondylalgia

References

Orchard, J., & Kountouris, A. (2011). The management of tennis elbow. Bmj, 342.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Increase your confidence in assessing and treating the Stiff Shoulder, Elbow & Wrist

What customers have to say about this course

- Senne Gabriëls30/12/24A complete understanding of elbow pathologies and management Very broad explanation of al the possible differential diagnosis and nice comprehensive management strategies with a big catalogue of exercises.Barbara14/12/24Really good Like always, perfect support to learn at your own rythm.

clear explanations and evidence based.

Thank you - Mika Tromp06/12/24Nice course! Explained the difference between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis nicely. Learned a few new things to use in clinical reasoning as well.Anneleen Peeters03/04/24Upper Limb Focus - The Wrist & Hand GREAT CONTENT!

Very happy with the way the course is presented; part videos, text and quizzes.

Great teachers, great refresher on the anatomy. - Dominik Meier01/04/24The Upper Limb Focus: Wrist & Hand CLINICALLY RELEVANT AND VERY WELL STRUCTURED COURSE!

This course is clinically relevant and very well structured. The wrist and hand is a very complex topic which has been described in a comprehensive and logical way. I can really recommend it. I like the theory and especially the cases. Thank you!Lieselot Longé29/12/23Upper Limb Focus - The Stiff Shoulder GOEDE CURSUS OM THUIS OP EIGEN TEMPO TE BEKIJKEN!

Dit is de 2de cursus die ik volg via physiotutors en net als de vorige cursus vond ik ook deze zeer leerrijk. Je krijgt dankzij deze cursus nieuwe inzichten in de behandeling van een stijve schouder. Er worden behandeltechnieken (o.a. mobilization with movement) getoond via video’s. Het leuke is ook dat je de cursus op je eigen tempo thuis kan volgen en na het afronden van de cursus kan je er nog steeds naar terug grijpen. Ik kijk ernaar uit om nog andere cursussen van physiotutors te ontdekken en raadt het ook anderen ten zeerste aan!. - Mieke Versteeg01/12/22Upper Limb Focus - The Elbow Inhoudelijk kwalitatief zeer hoogstaand.

Nog betere vertaling naar Nederlands zou toegevoegde waarde zijn.

Hulp per mail/telefonisch op ieder moment aanwezig/bereikbaar.