Cauda Equina Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment

Cauda Equina Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatment

Introduction & Pathomechanism

The cauda equina is the termination of the spinal cord. Typically the spinal cord ends at the level of L2, where it ends in cord-like nerves. It resembles a horse’s tail and therefore it is called the cauda equina. Cauda equina syndrome is typically a result of compression of the lower nerves S2, S3, S4, and S5. Compression of the higher nerve roots mainly affects the leg(s) and does not lead to the typical symptoms of for example saddle anesthesia. Cauda equina syndrome is a serious pathology requiring prompt action.

Pathomechanism

The most common cause is a massive lumbar disc herniation or prolapse which compresses the roots of the cauda equina. Other possible causes can be a mass caused by an infection or a hematoma or a bony fragment from a vertebral insufficiency fracture. In the prospective multi-center observational cohort study by Woodfield et al. in The Lancet (2022), the most affected levels were L4-L5 and L5-S1.

Epidemiology

Woodfield et al. in 2022 found that females between 30 and 39 years had the highest incidence of CES at 7.2 (95% CI: 4.7–10.6) per 100.000 females in the population per year. In the Scottish population referred for emergency surgical decompression, the crude incidence was 2.7 patients per 100.000 adults per year. According to Greenhalgh et al. (2018), cauda equina syndrome most frequently occurs between the ages of 31-50 years.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Picture

Signs and Symptoms

One or more of the following symptoms have to be present.

- Bladder and/or bowel dysfunction

- Reduced sensation in the saddle area

- Sexual dysfunction, with possible neurological deficit in the lower limb (motor/sensory loss, reflex change).

These symptoms can be associated with low back pain, as the most common cause of cauda equina syndrome is a lumbar disc herniation.

Three types of cauda equina syndrome onset can be observed, based on the patient’s presentation:

- Rapid onset of cauda equina symptoms with an absent history of back problems

- Acute onset of bladder dysfunction and or cauda equina symptoms together with a history of back problems and sciatica

- Gradually progressing onset of cauda equina symptoms with longstanding back problems. Often spinal stenosis is present.

The first cauda equina syndrome presentation type is rare. Type 2 is the most common form of cauda equina syndrome. The last type, with slow progression, occurs more frequently in older people and is usually not urgent. However, careful monitoring of symptoms is required, especially as people in this age group can be unaware of the importance of changing bladder and bowel function. They may often attribute it to their increasing age. Also, they may be less sexually active, which may mask symptoms of sexual dysfunction.

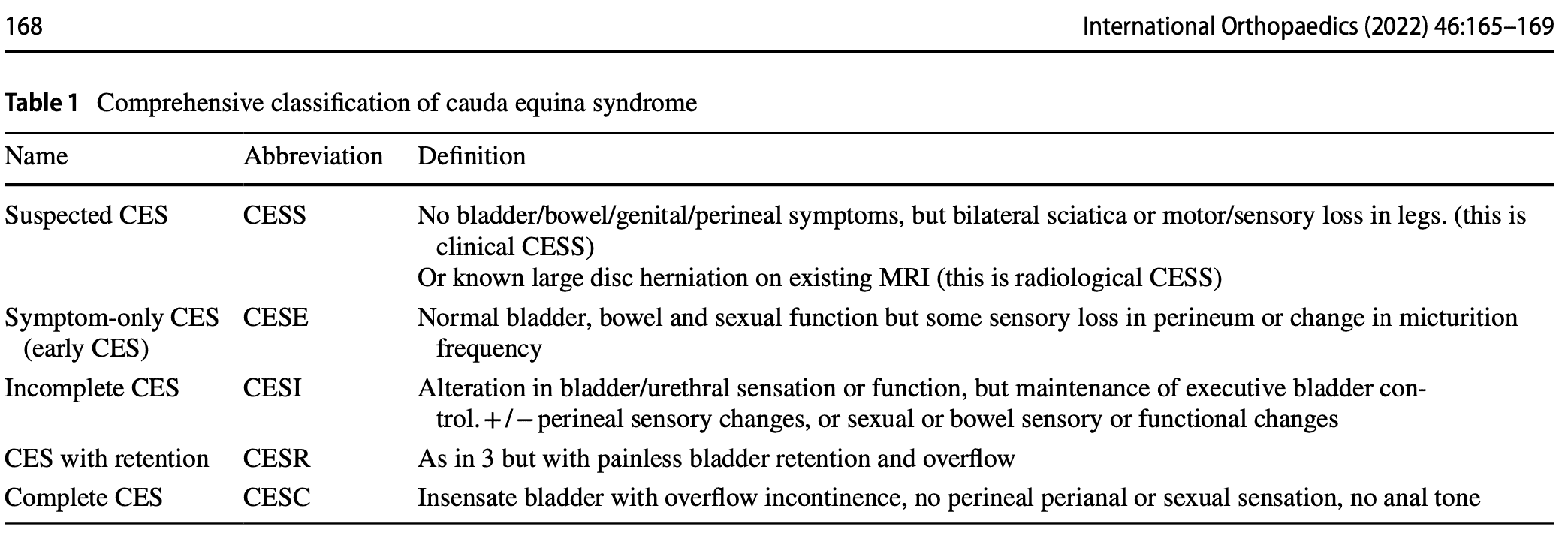

The classification above is based on the presentation of the symptoms. However useful and easy to remember, the following classification is the most commonly used.

CESI/CESR classification

This classification system defines 5 stages of cauda equina syndrome.

- Suspected cauda equina syndrome (CESS) is when there is bilateral sciatica or a loss of motor or sensory function in the legs. In the case of these symptoms, this is referred to as clinical CESS. Radiological CESS on the other hand is when a large disc herniation is present on MRI, which compresses the cauda equina. This stage can be accompanied by variable neurological symptoms and signs and a suggestion of sphincter disturbance.

- Early cauda equina syndrome (CESE) is defined as symptom-only cauda equina syndrome. There is a normal bladder, bowel, and sexual function. There may be a change in the micturition pattern, but the perineal sensation is normal. Or there may be a change in the perineal sensation with normal bladder function.

- CESI is defined as incomplete cauda equina syndrome. The patient has problems with urinating and these arise due to a neurogenic origin. These symptoms may include altered sensation with urinating, loss of desire to void, poor urinary flow, the need to strain, and an altered perineal sensation. But these symptoms do not lead to a loss of bladder function. These people have still executive control over the bladder and they may still void, even if it is more difficult.

- Cauda equina syndrome with retention (CESR) on the other hand refers to cauda equina syndrome with painless bladder retention. These patients are no longer in control of their bladder. Urine is retained and overflow is present, although painless. When patients get to this stage, it is impossible to reverse things around.

- Complete cauda equina syndrome (CESC) refers to a total loss of sensory and motor function

Examination

It is inappropriate to simply ask if the patient is incontinent. Incontinence is a late stage of CES, and in most cases before incontinence is reached there are subtle changes of urinary sensation, flow and frequency that must be enquired about. Similarly, both subjective and objective features of perineal, perianal and genital sensation need to be assessed. – From Lavy et al., International Orthopaedics (2022)

Subjective examination

The subjective examination is very important, especially early in the presentation of cauda equina syndrome. Five characteristic features of cauda equina syndrome have been recognized. There is however no chronology in the presentation of symptoms.

- Bilateral neurogenic sciatica, perception of bilateral weaknessReduced perineal sensation: sensory disturbance in the “saddle region”

- Urinary dysfunction and bowel dysfunction

- Bladder dysfunction is the most commonly reported symptom and can range from increased urinary frequency, difficulty in micturition, change in urine stream, urinary incontinence, and urinary retention.

- Loss or reduced anal tone may be evident if a patient reports bowel dysfunction.

- Bowel dysfunction may include fecal incontinence, inability to control bowel motions, and/or inability to feel when the bowel is full with consequent overflow.

- Loss of sexual function

- Saddle numbness

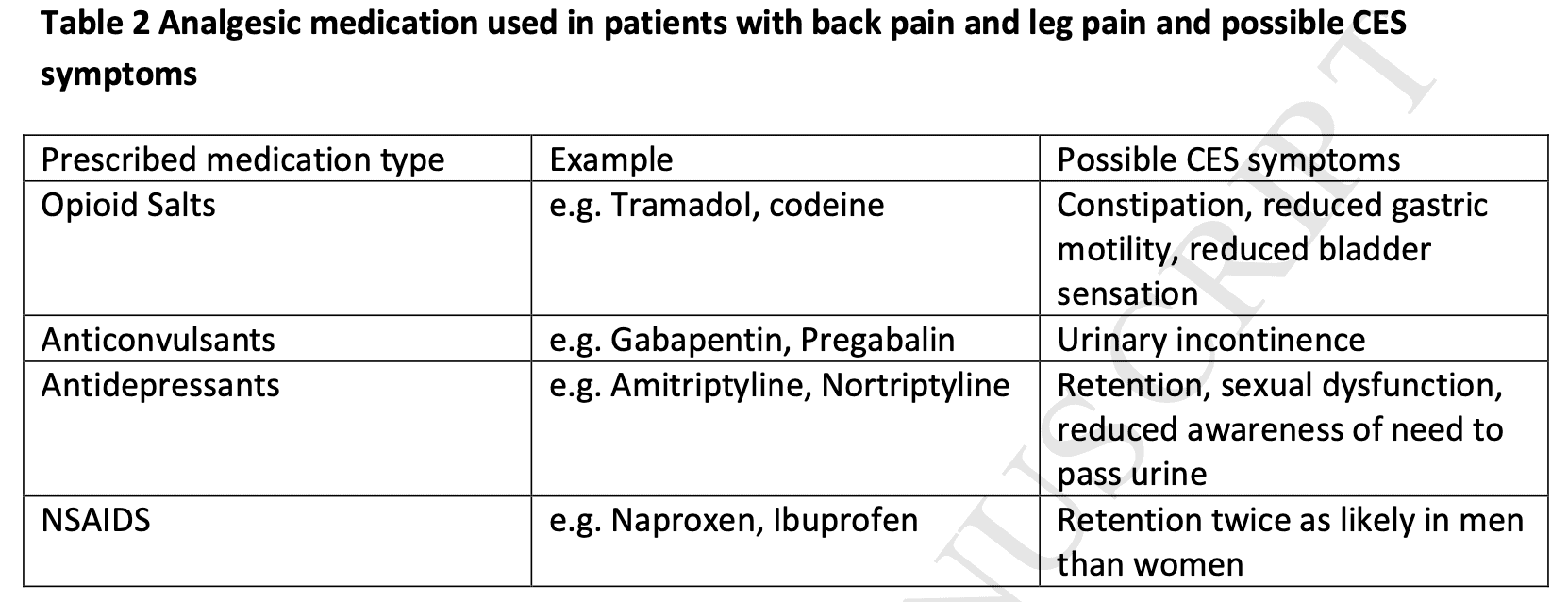

Importantly, regularly prescribed analgesic drugs for (back) pain like opioids can cause symptoms that masquerade as CES.

Clinical examination

The systematic review of Hoeritzauer et al. (2018) found 7 diagnostic accuracy studies for cauda equina syndrome but none was accurate in identifying the presence of the pathology.

A full neurological examination includes dermatome testing, myotome testing to find muscle weakness, and reflex testing. Sensory testing can be performed by evaluating the sensation to light touch and pinpricks in the saddle area including the buttocks, inner thighs, and perianal region.

If you suspect that the lesion is higher up (central nervous system), upper motor neuron tests such as the Babinski reflex, clonus testing, muscle tone testing, joint position sense, and gait testing should be performed.

Angus et al. (2021) retrospectively found that people with cauda equina syndrome more frequently had a loss of Achilles tendon reflex both unilaterally and bilaterally.

Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis but should be supported by imaging (MRI) as there can be different causes for the symptoms to arise.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

Timely and appropriate referral

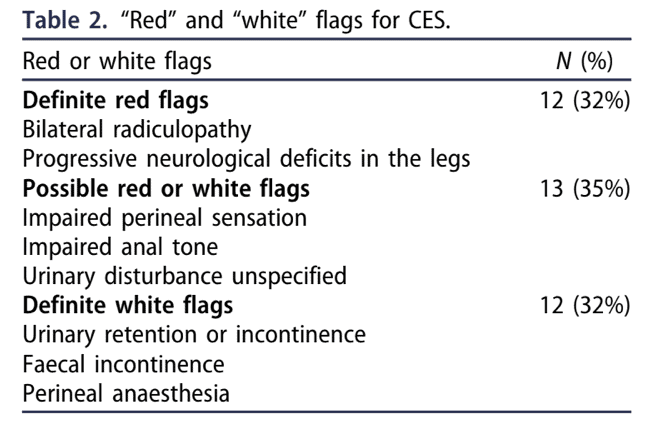

Individuals with cauda equina syndrome (CES) are typically referred late at a point when neurological damage cannot be restored. The symptoms and/or signs listed in guidelines for emergency referral, imaging, and treatment of CES are those of late-onset, irreversible CES. It might be too late to refer the patient at this point. Todd in 2017 proposed a set of true red flags and white flags. White flags refer to flags of “defeat and surrender”, meaning that if you find those signs and symptoms, the damage can be already irreversible, and thus, referral for that patient may already be too late. Therefore it is essential to screen for definite red flags as they warn for further avoidable damage ahead.

Emergency referral

When a patient complains of back pain, leg pain, or both, of recent onset (within two weeks) of any of the following symptoms, an emergency referral to the closest facility with Emergency MRI service is needed.

- Difficulty initiating micturition or impaired sensation of urinary flow;

- Altered perianal, perineal, or genital sensation S2-S5 dermatomes – the area may be small or as big as a horse’s saddle (subjectively reported or objectively tested);

- Severe or progressive neurological deficit of both legs, such as major motor weakness with knee extension, ankle eversion or foot dorsiflexion;

- Loss of sensation of rectal fullness;

- Sexual dysfunction – inability to achieve an erection or to ejaculate, or loss of vaginal sensation.

Urgent referral = referral within 2 weeks

In case your patient presents with sudden onset bilateral leg pain or unilateral leg pain that progressed to bilateral leg pain without CES signs or symptoms, you should make an urgent referral, meaning the patient needs to be seen within 2 weeks.

Safety netting

In early stages of cauda equina syndrome, symptoms can be vague. In order to make sure patients know how and when to seek care at the right moment, safety nets for patients experiencing back pain along with other symptoms are essential. When you make an urgent referral, it is also important to educate the patient in recognizing possible warning signs. In case signs and symptoms progress, you should make an emergency referral. The patient card below may be valuable to safety net your patient. This card can be found in 30 different languages at the following link.

References

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Learn More About the Most Common Spinal Pathologies

What customers have to say about this online course

- Shachaf Alexander19/07/24Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the spine

Interesting course packed with useful data and practical tools.

I highly recommend.Verena Fric25/11/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine GREAT COURSE ABOUT THE SPINE

great course, best overview about the different syndromes of the spine, very helpful and relevant for the work with patients - Peter Walsh01/09/22Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine 5 starsChristoph21/12/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine Really a well done course, using the modern ways of teaching. Compliments! Sometimes for me you entered too much into details instead of touching more important chapters of Spine treatment like techniques for the treatment of muscles and fascias

- John09/10/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine EXCELLENT COURSE HIGHLY RECOMMEND

As a newly graduated physiotherapist i highly recommend this course just to know you are on the right track with your patients. the information presented is very clear and easy to follow as well as the great physiotherapy style videos. It makes learning actually fun , thanks guys for all your hard work. Well deserved.Alexander Bender06/09/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine During the corona crisis, I booked many online courses and webinars, but none were as entertaining and well thought out as PhysioTutors’ courses.

All units are well summarized, meaningfully broken down and easy to understand.

I am looking forward to the other courses.

Many greetings from Germany. - GHADEER05/01/21Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine VERY INFORMATIVE AND UPDATED

for anyone who is lost in handling spine cases, this course is very helpful.MICHAEL PROESMANS20/12/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine HIGHLY METHODICAL, WITH PLENTY OF SCIENTIFIC REFERENCE

Clear, structured and well researched course concerning most common pathologies of the spinal complex.

Plenty of informative modules, with detailed video-analysis.

If you’re looking for a course to study in your own time, with enough depth and scientific background, then you’ve found a very good one here.

Bang for buck, a great course. - BENOIT08/05/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine After finishing the Orthopedic course for Lower & Upper limbs, I was looking forward to begin this Spine specific course.

Really good overview about all spine pathologies from epidemiology to diagnosis & treatment which made me more confident to care for my future patients.

ANOTHER GREAT COURSE !

The courses are well detailed with lot of informations and videos.

For me these 2 courses are must to see to learn and update knowledge for most common pathologies in Physiotherapy.Nicolas Cardon27/04/20Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Spine This is a very interesting course !

We can find many informations about the main pathologies and their differential diagnosis and about objective and subjective exam. Videos are clear and well designed.

It’s a very well course for these who wish complete their Orthopedic Manual Therapy curriculum.

A French Physio’