Clinical Bias-What is it and how to avoid it

We have just finished the first weekend of our part-time Master’s studies and we had to read a nice article in preparation for a lecture. It sparked great thoughts and got us thinking. Read more below.

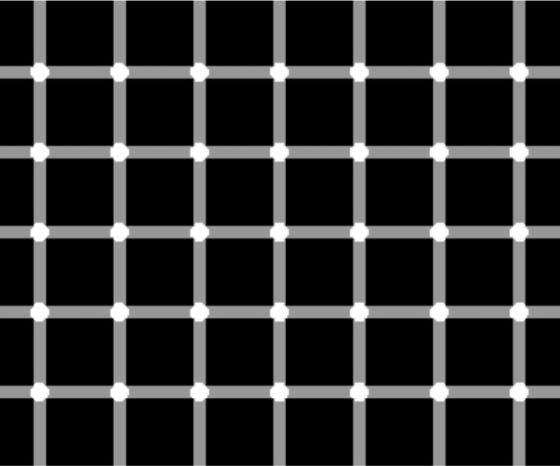

Have a look at the grid above. You’re probably seeing black dots in the matrix above, right? Even though they’re not there you still see them – at least you think so, or better, your brain thinks they’re there.

You might run into the same problem when evaluating a patient. Your decisions should be of the best possible quality as they have an effect on your patient’s health. As shown by the grid above, there are similar pitfalls affecting your clinical decision-making: cognitive biases. Your brain plays a trick on you making you prone to jump to conclusions using heuristics instead of systematic decision-making.

There are several possible pitfalls we may encounter in our practice or clinical decision-making:

1. The representativeness heuristic

It describes the assumption that something that seems similar to other things in a certain category is itself a member of that category.

Example:

Participants were presented with descriptions of people who came from a fictitious group of 30 engineers and 70 lawyers. They were then asked to rate the probability that the person described as an engineer. Keeping in mind that only 30% were engineers, the participants’ judgment was much more affected by the extent to which the description matched the stereotype of an engineer (e.g. “Steve is conservative and careful”) than by the base rate (30% were engineers). This shows that representativeness had a greater effect on judgments than did knowledge of the probabilities. (Kahneman & Tversky)

The same heuristic has been shown in nursing. Nurses were given two fictitious scenarios of patients with symptoms suggestive of either a heart attack or a stroke and asked to provide a diagnosis. The heart attack scenario sometimes included the additional information that the patient had recently been dismissed from his job, and the stroke scenario sometimes included the information that the patient’s breath smelt of alcohol. The additional information had a highly significant effect on the diagnosis and made it less likely—consistent with the representativeness heuristic—that the nurses would attribute the symptoms to a serious physical cause. The effect of the additional information was similar for both qualified and student nurses, suggesting that training had little effect on the extent to which heuristics influenced diagnostic decisions. (Klein, 2005).

Representativeness has a greater effect on judgments than knowledge of the probabilities.

2. The availability heuristic

Placing particular weight on examples of things that come to mind easily, as they are easily remembered or were recently frequently encountered.

Example:

You just read a great editorial on the incidence of SI Joint dysfunction in LBP. Suddenly, a high number of LBP patients you see SURELY MUST HAVE SI joint problems It seems obvious to you in the heat of the moment as things that come to mind easily are likely to be common but chances are that your brain is misleading you. In order to avoid this ask yourself whether the information is truly relevant, rather than simply easily available.

3. Overconfidence

This is a tricky one. We all think we are masters of our trade, don’t we ;). But to use our knowledge effectively, we have to know the limitations. It is crucial that we identify gaps in our knowledge which in turn lead to suboptimal treatment. Overconfidence can also result in hasty decision-making in clinical diagnosis. Therefore it is key to be aware of the limits of our knowledge and to keep it up to date. Make a habit of asking colleagues for opinions and do your research to stay up to date.

4. The confirmatory bias

It’s the tendency to look for information that confirms your pre-existing expectations. On the other end, information that contradicts the pre-existing expectation may be disregarded.

Asking questions, or worse stop asking questions, during patient history taking when information obtained fits with your early hypothesis. To avoid confirmatory bias, rather ask questions that may contradict or discard your early hypothesis and don’t regard that information as irrelevant.

Orthopedic Physiotherapy of the Upper & Lower Extremities

Boost Your Knowledge about the 23 Most Common Orthopedic Pathologies in Just 40 Hours Without Spending A Fortune on CPD Courses

5. The illusory correlation

This one is especially prevalent in statistical analysis. It’s the tendency to perceive two events as causally related when the connection between them is, at most, coincidental or even non-existent. Surely there is overlap with confirmatory bias when an outcome fits pre-existing ideas. A popular example is a claim that homeopathy works when a patient improves after being administered a homeopathic drug even though there is no sound evidence. Homeopaths will likely remember occasions when a patient improved after treatment – illusionary correlation.

Don’t fall for these incorrect beliefs which may, in turn, lead to suboptimal practice.

It surely got us thinking and reinforced us to stay alert for biases and have an open mind each and every time we see a patient.

Thanks a lot for reading,

Andreas

Andreas Heck

CEO & Co-Founder of Physiotutors

NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published.