Effectiveness of Pelvic Exercises on Knee Valgus

Introduction

Dynamic knee valgus is characterized by an inward angulation of the knee during dynamic tasks. Biomechanically, this alignment increases compressive load on the lateral knee compartment and shear forces on the ACL and medial collateral ligament. During high-demand activities such as jumping or rotational movements, dynamic knee valgus—sometimes combined with tibial external rotation—raises the risk of ACL injury. Frontal plane knee stability relies heavily on the hip abductors, and given the anatomical proximity and role of the deep pelvic stabilizers in hip control, active pelvic stabilizationdeserves greater attention. This study explores the impact of pelvic exercises on knee valgus by implementing a targeted six-week pelvic stabilization program. The objective was to increase the activity of pelvic stabilizing muscles and evaluate their effect on dynamic knee valgus.

Methods

Participants

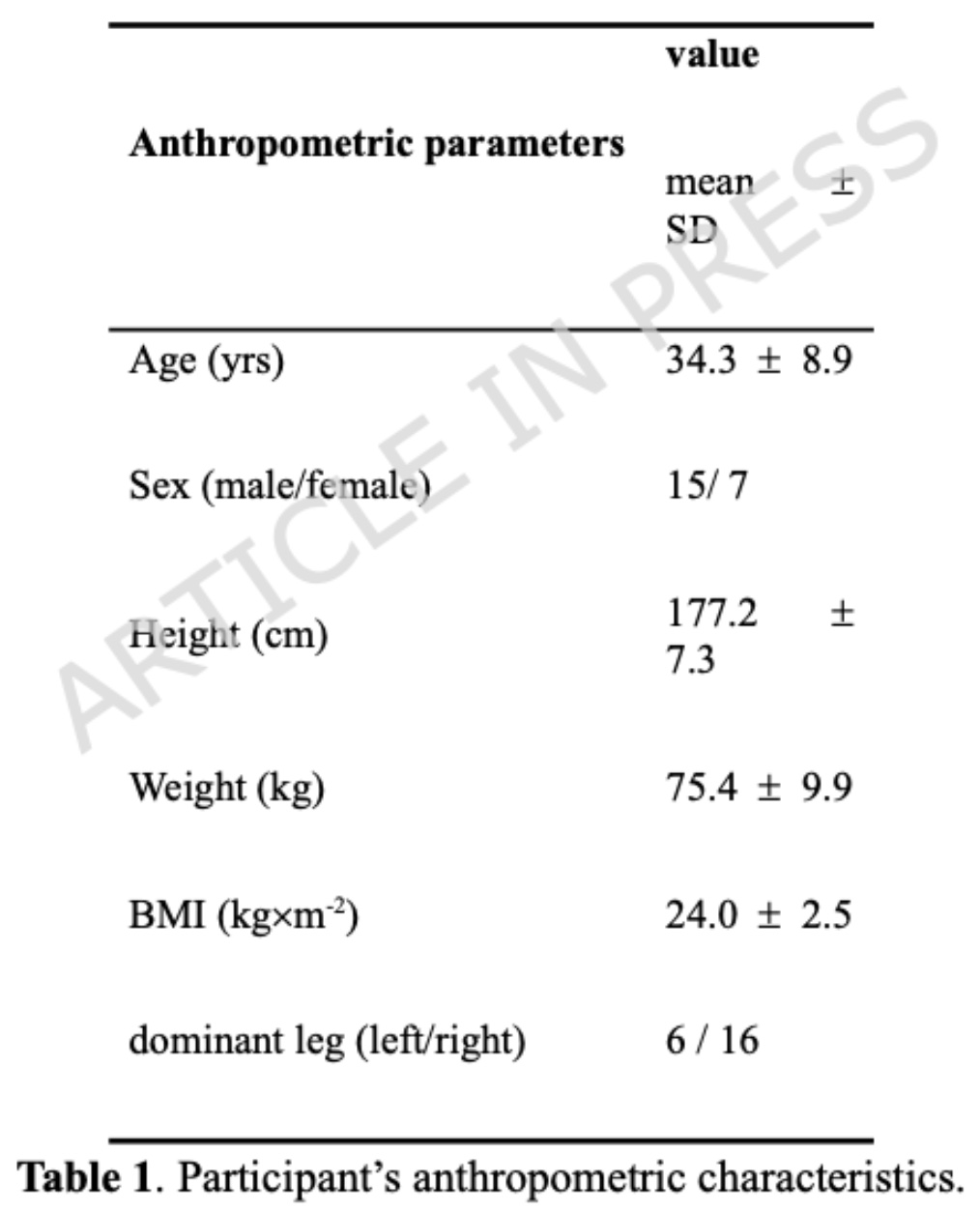

Twenty-two healthy, physically active adults participated in the study (15 men and 7 women; mean age 34.3 ± 8.9 years).

Inclusion criteria

- Age between 18 and 50 years

- No history of lower limb injury

- Dynamic knee valgus (DKV) greater than 2% of lower limb length during a single-leg squat

- DKV measured at 15% of squat depth

Exclusion criteria

- Recent musculoskeletal pain

- Neurological disorders

- Any condition limiting participation in exercise

Assessments

Overall well-being was assessed using the SF-36 questionnaire. Sports activity level was measured using the Tegner score, and subjective knee function was evaluated with the Lysholm score. Anthropometric data and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Dynamic knee valgus, muscle activity, and isometric muscle strength were also recorded.

Procedure

All participants attended a familiarization session to learn proper single-leg squat technique and the program-specific exercises. Baseline assessments (SF-36, Tegner score, and Lysholm score) were then completed. Participants subsequently followed a six-week training program, three times per week, consisting of progressively advanced pelvic stabilization exercises targeting the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and vastus medialis obliquus, while improving pelvic control. All outcome measures were reassessed after the six-week intervention.

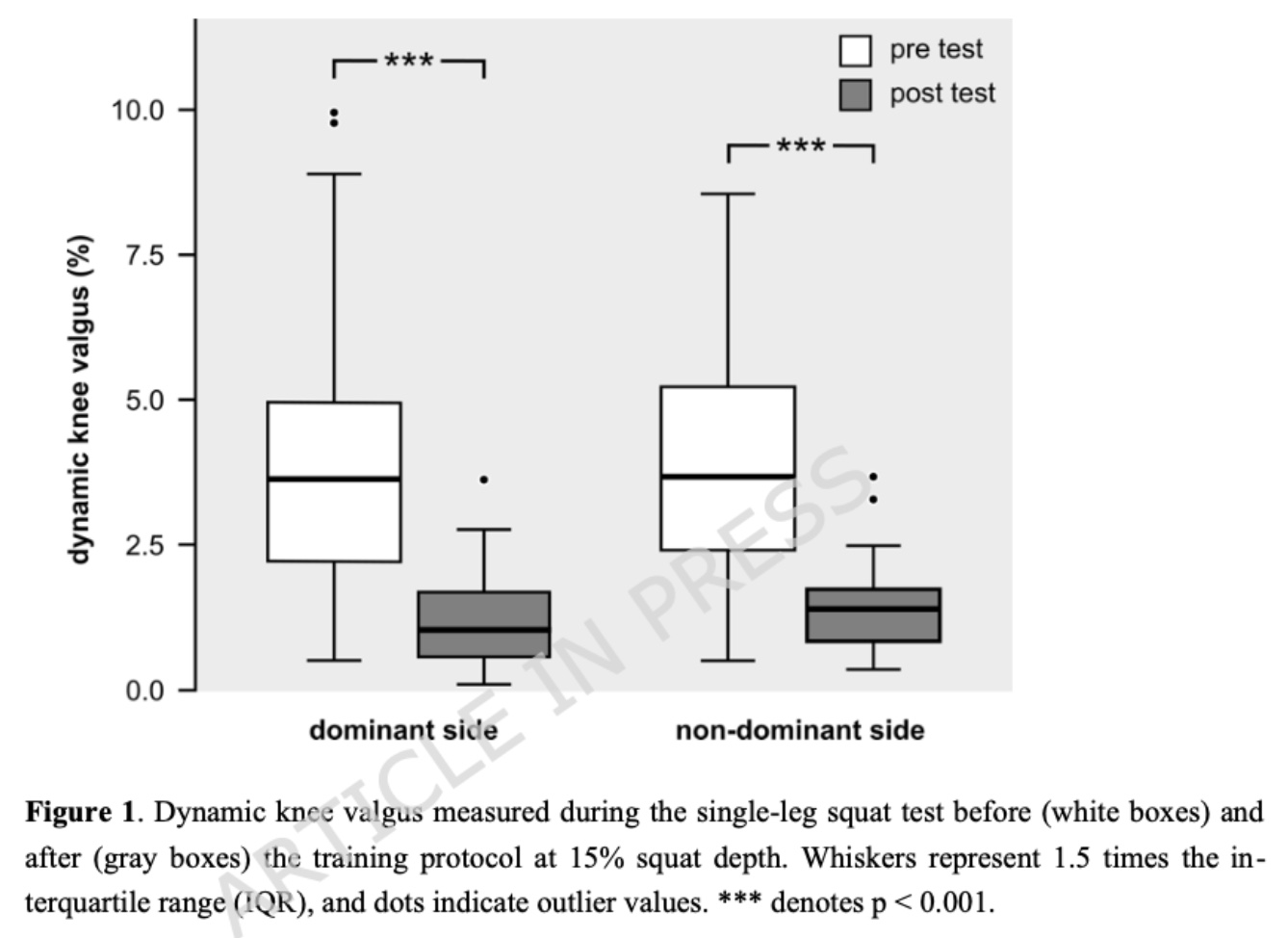

Dynamic knee valgus assessment

Dynamic knee valgus was evaluated using video capture and a dedicated motion analysis system. Participants completed 10 single-leg squats on both the dominant and non-dominant limbs, descending to their maximum comfortable depth. Throughout the test, they were instructed to keep their hands positioned on their hips to standardize upper-body movement.

Maximum isometric muscle force measurements

Maximum isometric strength was measured using a wireless dynamometer. The gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, and biceps femoris muscles were evaluated. The assessment procedure was performed by two physiotherapists and standardized to properly isolate the tested muscle.

Intervention

The six-week intervention program aimed at investigating pelvic exercises on knee valgus was designed according to the FITT principles (Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type). The primary objective was to improve neuromuscular control, with exercises progressing from unloaded positions to functional tasks. Each week included two supervised sessions (40–45 minutes) and one 15–20 minute home-based session supported by instructional videos. Intensity was maintained at a perceived exertion of 12–14 on the RPE scale. Exercise progression involved increasing repetitions, gradually incorporating multi-limb movements, and introducing unstable surfaces and light perturbations. In-clinic sessions began with a mobility warm-up followed by 10–15 minutes of stretching.

Phase 1 (Weeks 1–2): Low-load, static motor control exercises on stable surfaces targeting deep core stabilizers (transversus abdominis, multifidus) and selective glute activation, while maintaining neutral lumbar lordosis.

Phase 2 (Weeks 3–4): Integration of core activation into functional movements (squats, lunges) with bands and proprioceptive work on stable to unstable surfaces, emphasizing coordinated glute, quadriceps, and core control.

Phase 3 (Weeks 5–6): Dynamic and single-leg tasks with perturbations and landing control to maintain lumbopelvic stability during functional, dynamic activities.

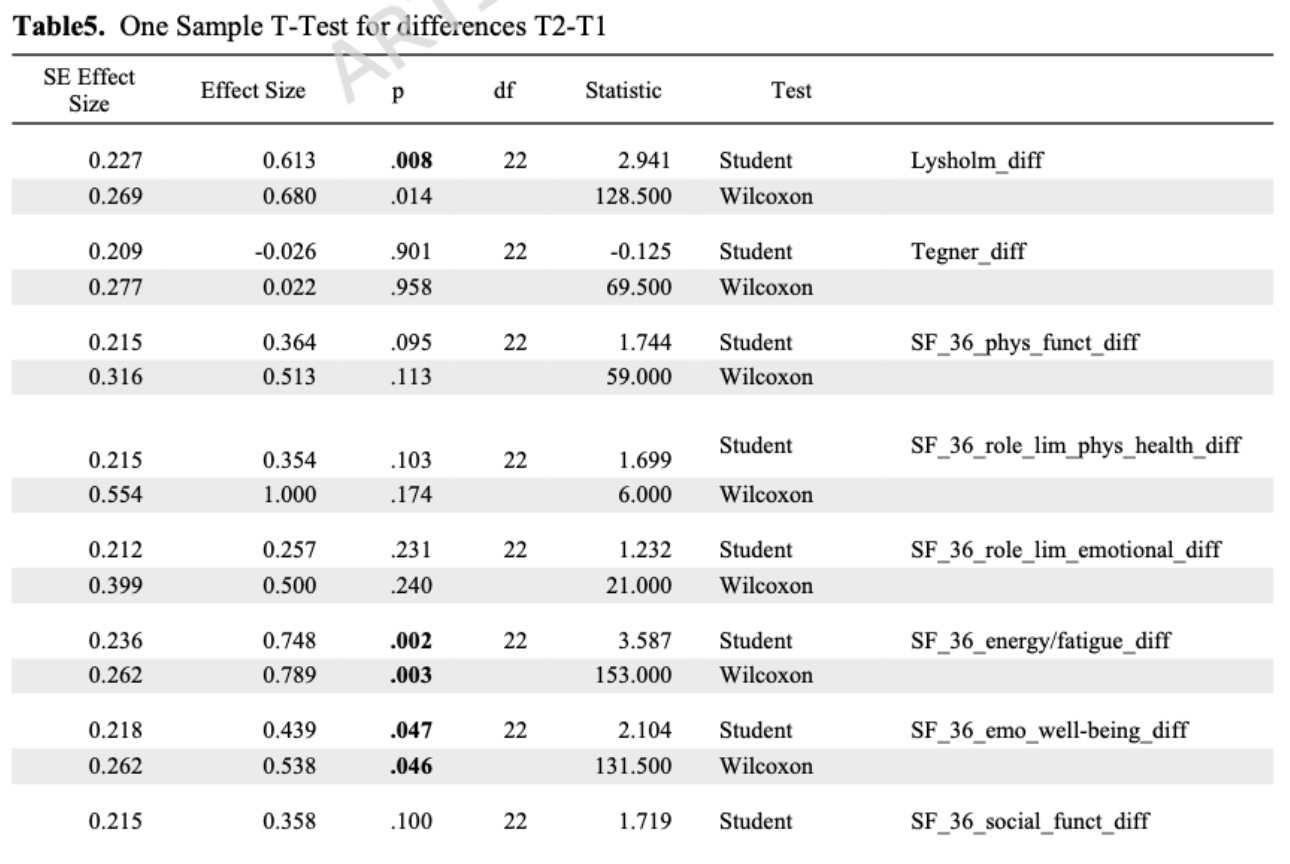

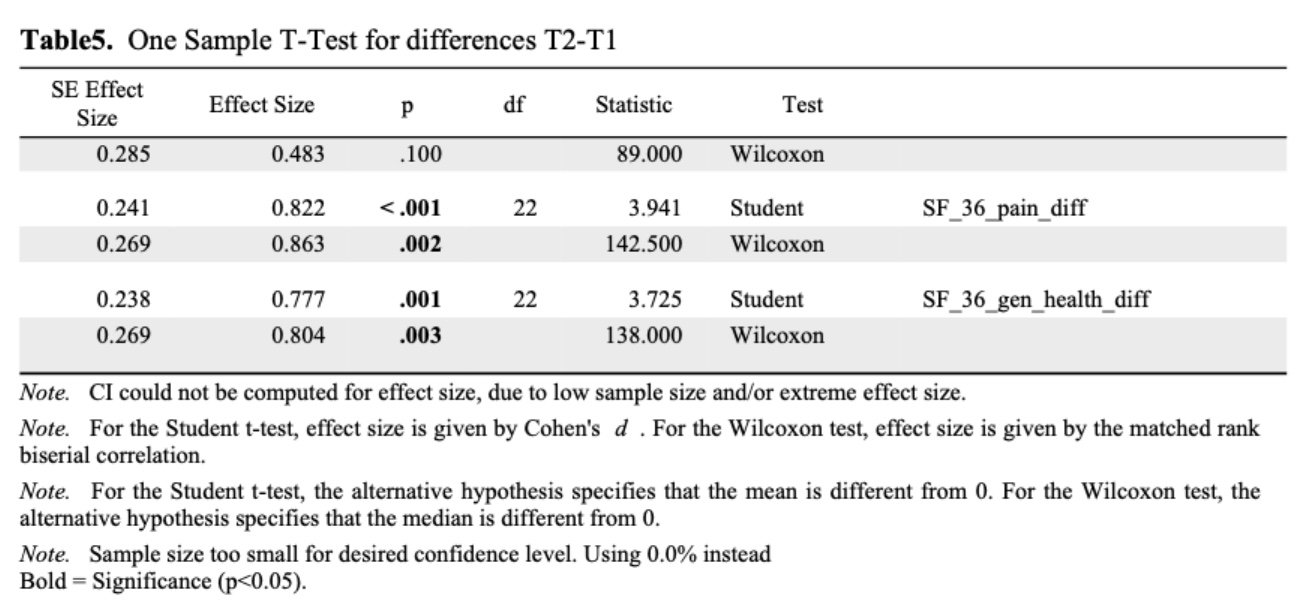

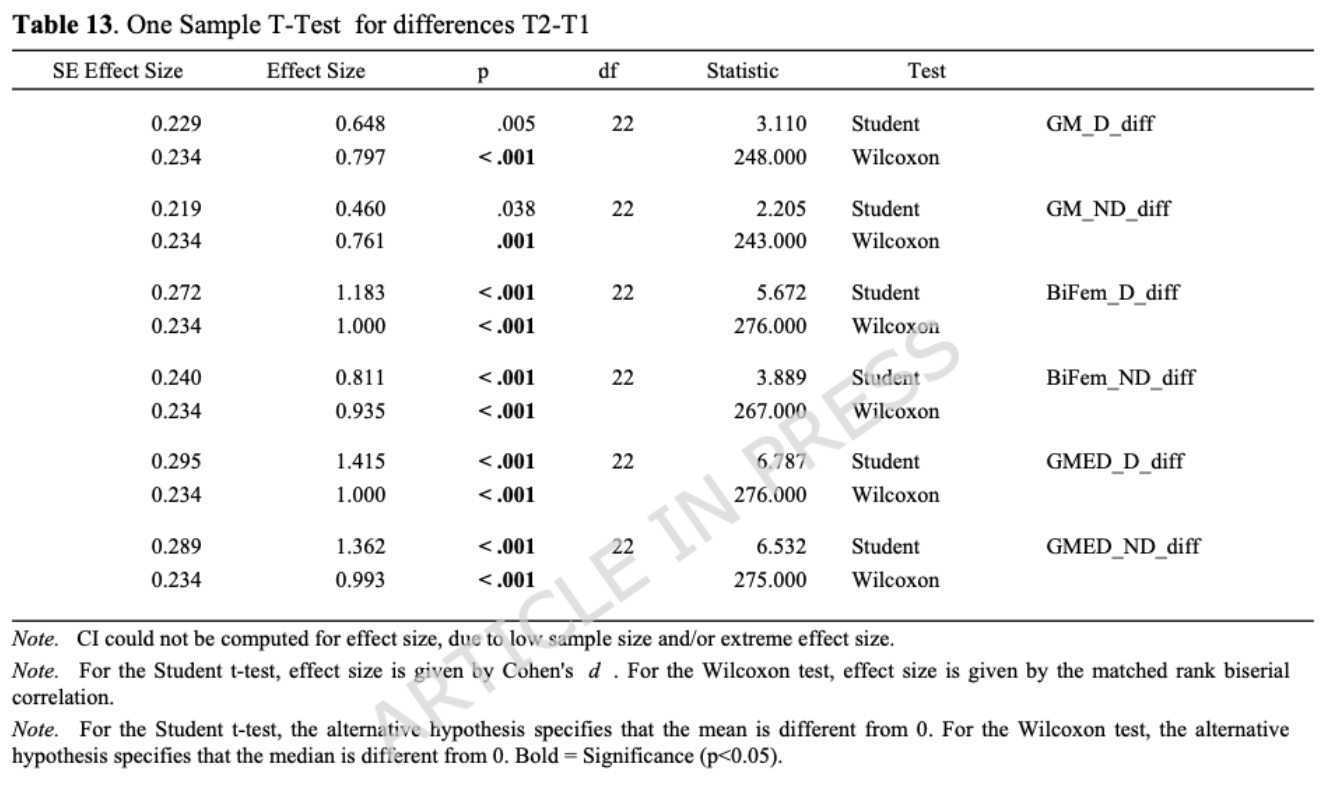

Statistical methods

Normality of pre- and post-intervention data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Depending on data distribution, changes were analyzed using either a paired-sample t-test or the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The Tegner score showed no significant difference between pre- and post-test assessments, indicating that overall activity levels remained stable throughout the study period.

Lysholm scores improved following the six-week intervention, indicating a reduction in knee pain and an improvement in subjective knee function. Similarly, SF-36 results demonstrated an improvement in overall well-being at post-test compared with baseline.

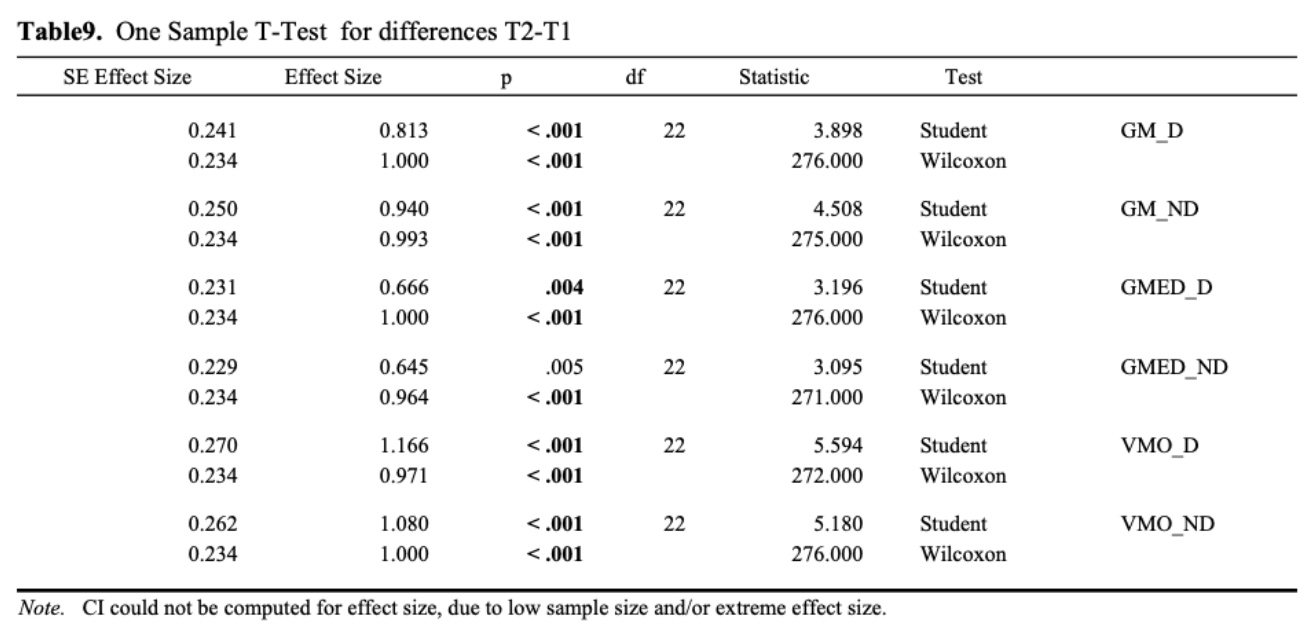

EMG amplitude increased on both the dominant and non-dominant sides for all muscles assessed at post-test. The smallest changes were observed in the gluteus maximus, whereas the vastus medialis – less directly involved in frontal plane knee control and dynamic knee valgus – showed marked improvement.

As expected, the proposed training program increased the maximal isometric strength for all the tested muscles.

Dynamic knee valgus during the single-leg squat, measured at 15% of squat depth, decreased on both the dominant and non-dominant sides at post-test.

Questions and thoughts

Interestingly, the study did not directly assess pelvic floor muscles using EMG. Instead, only the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, and vastus medialis were evaluated, with resisted isometric testing also including biceps femoris strength. At first glance, one might have expected the study to focus on pelvic floor stabilization muscles specifically, given the extensive research on gluteal pelvic stabilizers. This raises the question of whether the study truly addresses a significant gap in the existing literature. Future research could investigate the effects of pelvic floor stabilization training on dynamic knee valgus; however, the available clinical tests to assess the contribution of pelvic floor muscles to knee valgus remain unclear.

Further research is needed to explore how the proposed pelvic exercises for knee valgus translate to functional tasks. Assessments of neuromuscular timing, proprioception, and sport-specific performance are needed to determine how well the training translates to real-world activities. Quantification of sport-specific external loads would further improve understanding of the program’s applicability and help clinicians design task-relevant training programs.

Finally, the feasibility of implementing an intensive program of pelvic exercises for knee valgus in typical clinical settings remains uncertain. Conducting two 45-minute sessions and one 15–20 minute session per week may not be practical for most patients or clinicians.

Talk nerdy to me

In the control group, the authors’ hypothesis was supported: the specific pelvic exercises for knee valgus, targeting pelvic stabilization and strengthening, led to increased pelvic muscle activity. Additionally, EMG testing combined with dynamic knee valgus assessment during a single-leg squat provides strong evidence of a link between pelvic floor activation and improved knee kinematics. However, as no true control group was included, the specific effect of this targeted training program remains uncertain. It is possible that a more general strengthening program, not specifically designed to activate the pelvic floor, could produce similar improvements. If so, such a program might be more feasible in clinical practice, as it could address multiple objectives simultaneously.

One limitation of this study is the small number of participants, which may introduce potential statistical bias. The Shapiro–Wilk test, used to assess whether the data follow a normal distribution, loses power with small sample sizes. A normal distribution is symmetric and bell-shaped, with most values clustered around the mean and fewer values at the extremes. This test is important because its results guide the choice of statistical analysis for comparing pre- and post-intervention measurements. When data are normally distributed, a paired t-test is used to compare means; when data are not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test is used to compare ranks or medians. Both tests allow detection of significant differences.

In this study, the combination of a small sample size and heterogeneity in participant characteristics (sex, weight, height, etc.) may reduce the reliability of the Shapiro–Wilk test, potentially affecting the validity of the paired t-test results. In other words, even if the Shapiro–Wilk test indicates normality, this may reflect the small sample size rather than true normality, and the heterogeneity of the participants raises further concerns about the distribution of the data. This may lead to skewed results if a paired t-test is applied.

It appears the authors ran both the Wilcoxon and paired t-tests for all parameters assessed. This approach resulted in differences in significant findings, as illustrated in Table 13 for the gluteus medius dominant (GM_D) and non-dominant (GM_ND) sides, where the Wilcoxon test detected significant differences while the paired t-test did not.

Take-home messages

Pelvic exercises for knee valgus may help reduce dynamic knee malalignment during single-leg squat performance. A structured six-week program, with three sessions per week, can improve activation of gluteal and thigh muscles, enhancing pelvic stability. Improvements in knee function (Lysholm score) and overall well-being (SF-36) were observed post-intervention. The lack of a control group means it is unclear whether pelvic-specific training is superior to general strengthening programs. Clinicians should consider patient feasibility when designing training programs, as intensive protocols may be challenging in typical clinical settings.

Reference

THE ROLE OF THE VMO & QUADS IN PFP

Watch this FREE 2-PART VIDEO LECTURE by knee pain expert Claire Robertson who dissects the literature on the topic and how it impacts clinical practice.