What should Physiotherapy after Spinal Surgery consist of?

Introduction

In a lot of people who underwent spinal surgery for their lower back pain problems, successful outcomes have remained absent. The number of failed back surgeries is high and urges us to find other care paths for people with low back pain. In non-surgical populations, cognitive functional therapy seems to be an effective strategy for relieving pain and improving function. The implementation of cognitive functional therapy in surgical populations seems promising but it has not yet been studied in people who have already undergone surgery for their lower back pain. Therefore, this study aimed to shed light on this topic!

Methods

This RCT was set up as a superiority trial that compared cognitive functional therapy and core exercises combined with manual therapy (CORE-MT) on the outcomes of pain and function in people with chronic low back pain after spinal surgery.

Eligible candidates were between the ages of 18 and 75 and sought treatment for their low back pain which lasted for at least 12 weeks after they had undergone lumbar spinal surgery. Back pain was their primary pain area. Further, they had to be independently mobile with or without aids. A score of at least 14% on the Oswestry Disability Index and a minimum pain intensity of 3/10 on the NRS scale were required to be included.

The intervention delivered was cognitive functional therapy (CFT). This intervention was developed to improve outcomes in pain and disability by helping patients self-manage their persistent low back pain. This is done by addressing specific psychological pain-related cognitions, emotions, and behaviors that contribute to their pain and disability. These include fear avoidance, seeing pain as a threat, protective muscle guarding, etc. The intervention has 3 main components:

- Making sense of pain

- Exposure with control

- Lifestyle change

This intervention was compared against core exercises combined with manual therapy (CORE-MT). This program consisted of 1 weekly supervised session and 2 home exercise sessions. The core exercises were both static and dynamic. Both treatments were individualized, supervised, and delivered pragmatically from 4 to 12 sessions of 60 minutes every week.

The control arm received CORE-MT, but it wasn’t specified what the manual therapy sessions consisted of in the original publication. Yet when contacting the authors, more details were provided.

- For the CORE exercises, a cat-camel spine flexion and extension exercise was used as a warm-up. A supine-lying abdominal brace was taught to participants in a neutral spine position. For core endurance, bridge exercises (bridge, prone bridge, and side bridge), 4-point kneeling exercises (ie, bird-dog), and supine exercises (ie, dead bug, curl-up) were performed. The exercises were individualized, and the exercises were carried out using body weight and on unstable surfaces according to the progress of each participant.

- The manual therapy included joint mobilization, stretching, and myofascial trigger point release

The primary outcomes were pain intensity over the previous week and function. The first was evaluated using the NRS. The latter uses the Patient-Specific Functional Scale where the final score is a sum of the activity scores/number of activities.

Results

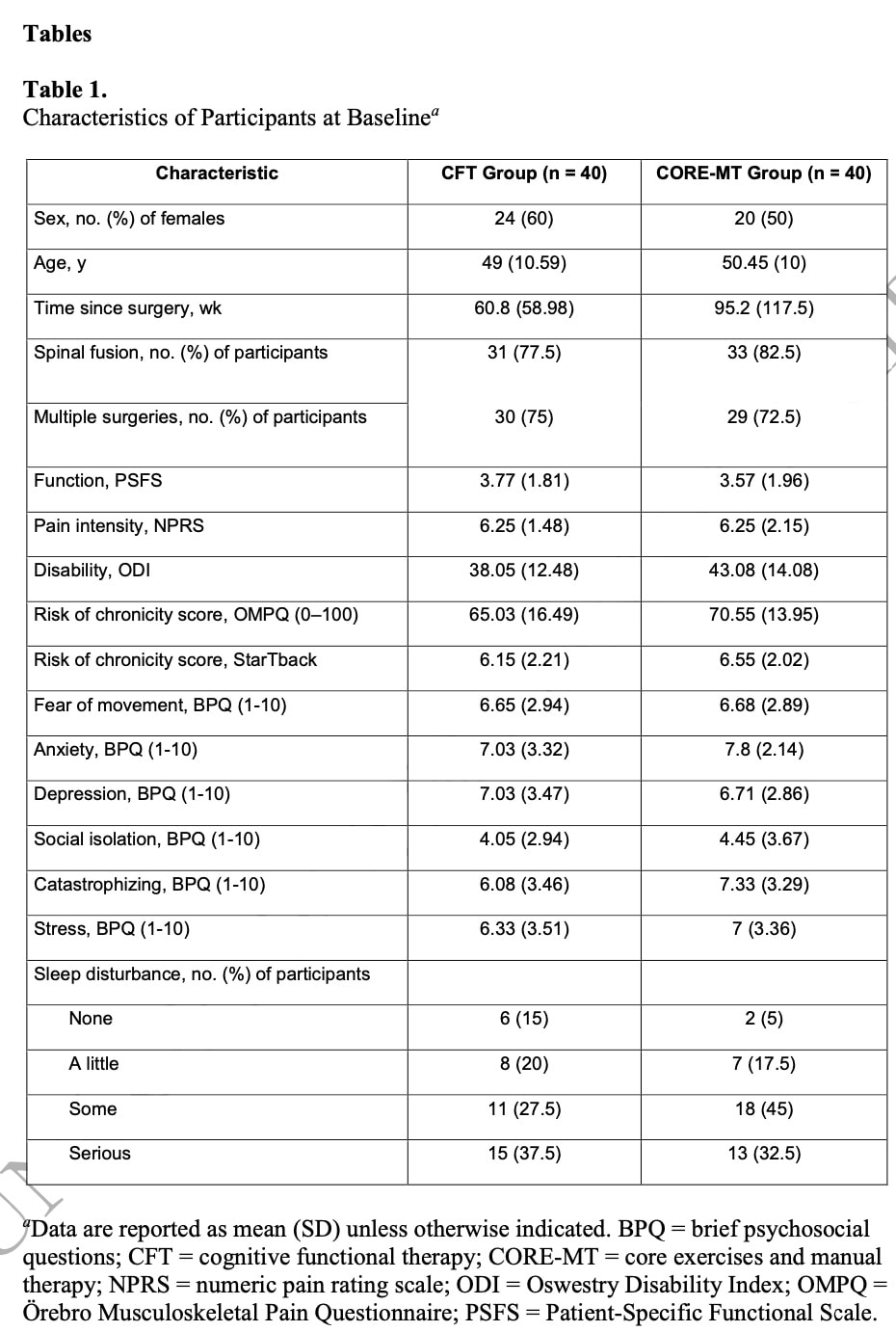

Eighty participants were included in the RCT and equally divided into the intervention and control groups. In every group, participants had 5 to 6 individualized sessions and were discharged at approximately 10 to 11 weeks. The mean duration of the CFT was slightly longer than the CORE-MT.

The baseline characteristics revealed that this population had longstanding complaints, with a mean time since the first surgery of 78 months! In 80% of the cases, they underwent spinal fusion, and more than 70% of the participants in both groups had received multiple spinal surgeries. They had high baseline pain intensity levels, reflected by a mean of 6.25/10 NPRS score. They had low functionality, and high scores on most domains of psychosocial factors.

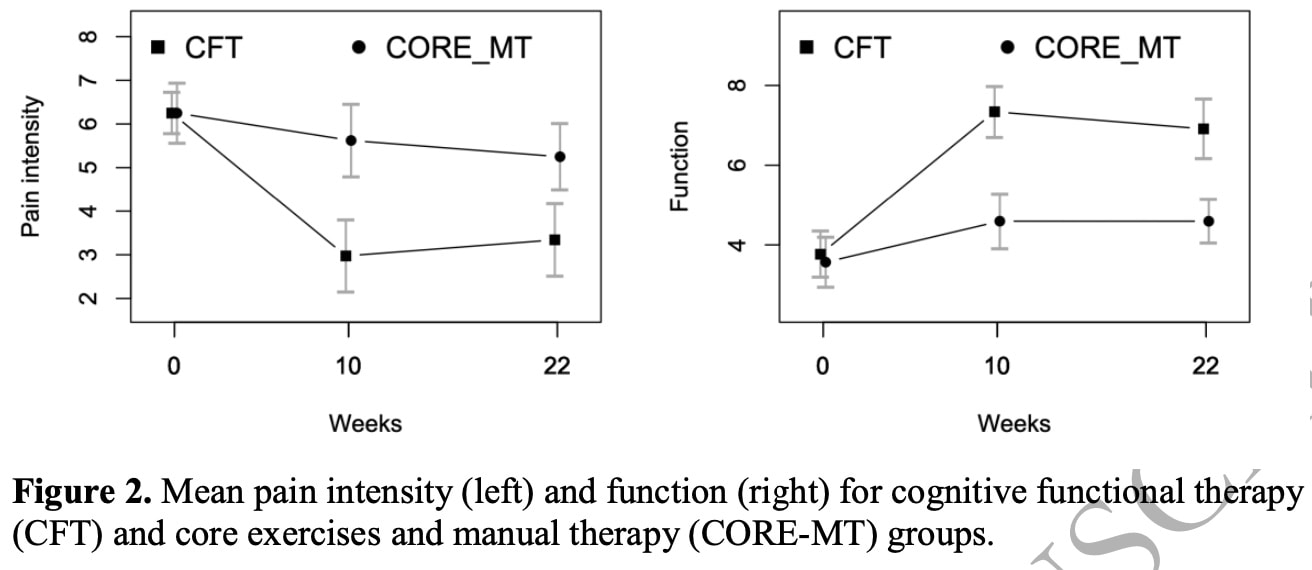

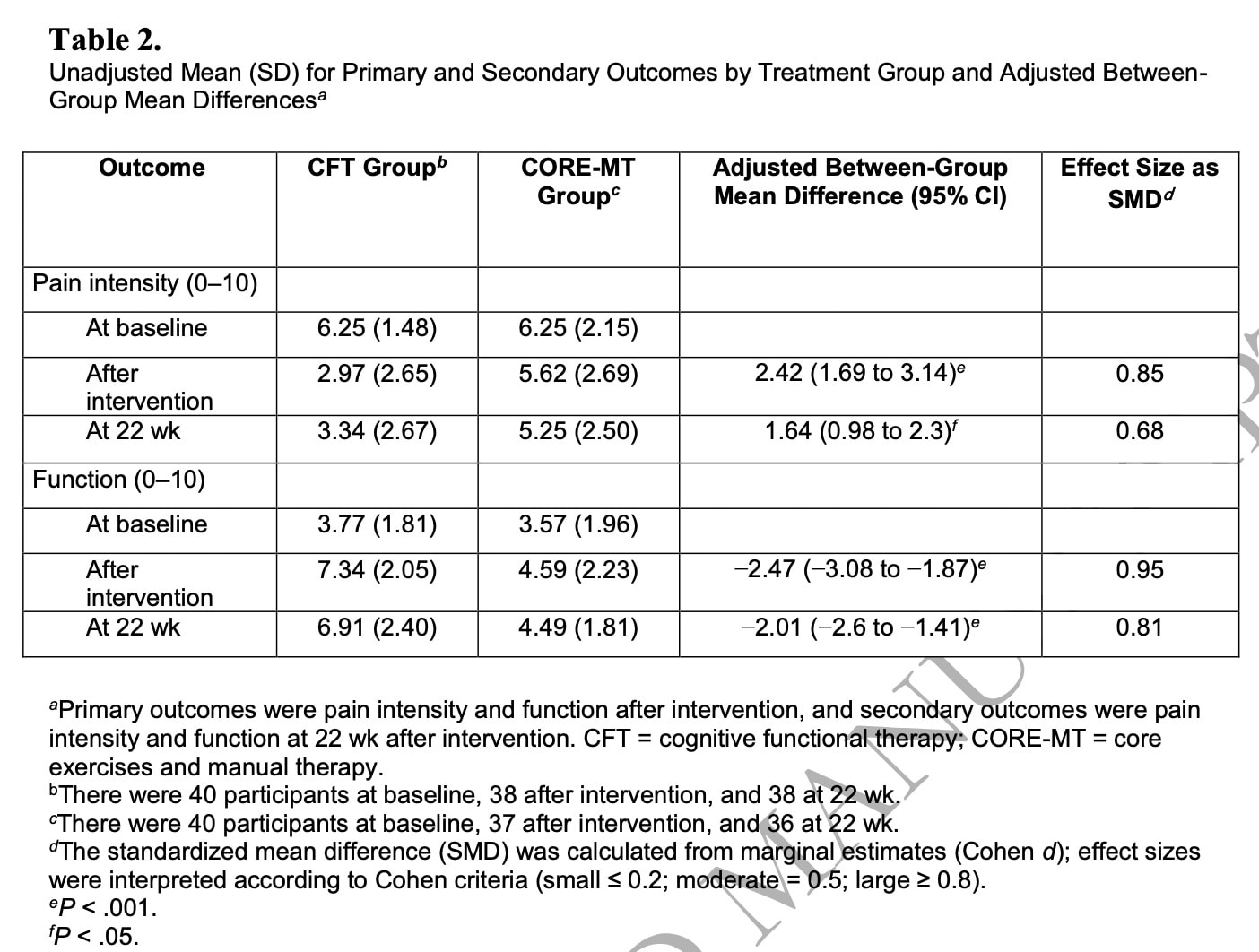

The primary outcome analysis revealed a significant between-group mean difference in favor of the CFT group both for reducing pain intensity (MD = 2.42; 95% CI = 1.69 to 3.14; effect size = 0.85) and improving function (MD = −2.47; 95% CI = −3.08 to −1.87; effect size = 0.95). The effect sizes were large.

This difference in favor of CFT was maintained after 22 weeks, although only the effect size for function remained large. For pain, the effect size at 22 weeks was moderate.

Most secondary outcomes confirmed the findings of the primary analysis, with medium to large effect sizes here as well. The only exceptions were anxiety and sleep quality. Considering patient satisfaction, disability, fear of movement, catastrophizing, and social isolation, the effect of CFT was also supported by the results of the secondary analysis.

Questions and thoughts

Physiotherapy after spinal surgery is mostly more conservative in terms of mobilizations and probably will take an active approach, but as this RCT is specified to deliver manual therapy, it is likely to include some passive form of treatment. Yet, manual therapy or physiotherapy after spinal surgery is often limited in passive possibilities, especially when subsequent vertebrae are fused as was done in the majority of participants. So I am curious to see what their understanding of manual therapy was. Was it manipulations, or mobilizations? The publication did not specify this, but the corresponding author was kind enough to share this information. The manual therapy in this study included joint mobilization, stretching, and myofascial trigger point release. But further than that, nothing is specified. That is a pity.

The details on the recruitment of the study specified they were recruiting patients who were seeking treatment for low back pain with a duration of at least 12 weeks after surgical intervention in the lumbar spine for lumbar or sciatic pain. Further, they excluded participants if their primary pain was not in the lumbar region and if leg pain was the primary problem (due to nerve root compression or disc prolapse with true radicular pain/radiculopathy, lateral recess, or central spinal stenosis). It seems that this is a discrepancy in the inclusion criteria as one of the criteria for diagnosing radicular pain is that the leg pain is worse than back pain.

I understand that they wanted to include participants operated on for low back pain, and those with radicular pain in the leg certainly have a low back problem. The population may be heterogeneous since some people would possibly have had a specific cause for their pain (nerve root compression for instance), while others may have undergone surgery for nonspecific causes of low back pain. This is highly recommended against, but often performed.

Talk nerdy to me

This study was pragmatically designed, which I think is an excellent approach as it most closely resembles clinical practice. RCTs are mostly very strict designs with narrow inclusion criteria and often this is reflected in treatments that are delivered in a one-size-fits-all manner. Here the pragmatic design was to let the treating physiotherapist decide when to discharge the participant. It is unclear whether the physiotherapist was also able to modify the approach to the needs of the participants or if he had to follow a given set of predefined exercises and progressions.

A very good finding was the high retention of participants at the follow-up moment. Especially as this population was characterized by long-standing pain after spinal surgery. They are seen as having “failed back surgery syndrome”. To me, these results are very promising as this population is often tough to treat as they are confronted with more than just pain. They may be very anxious, frustrated, and pessimistic because they understand that the surgery hasn’t helped their pain go away. Therefore, this study lights a promising path of care for people who are often given up on by medical professionals.

The possibility that the slightly longer duration of CFT than CORE-MT had influenced the outcomes was examined by including it as a confounding factor in the analysis. No further mention was made about this difference, so we assume that it did not impact the findings.

Take home messages

This trial compared cognitive functional therapy and core exercises combined with manual therapy for relieving pain and improving function in people with chronic low back pain after spinal surgery.

It made a strong statement as this paper included patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Where the surgery was not capable of relieving their pain, this study did by using cognitive functional therapy. This treatment aims to address specific psychological pain-related cognitions, emotions, and behaviors that contribute to their pain and disability and target these. In one of our previous research reviews, we discussed what CFT can include, so I recommend you read the “Questions and Thoughts” section!

Reference

Additional reference

HOW NUTRITION CAN BE A CRUCIAL FACTOR FOR CENTRAL SENSITISATION - VIDEO LECTURE

Watch this FREE video lecture on Nutrition & Central Sensitisation by Europe’s #1 chronic pain researcher Jo Nijs. Which food patients should avoid will probably surprise you!