Heavy Resistance Training for Long-Term Muscle Strength Preservation

Introduction

It is commonly known that muscle mass and function decline with increasing age. Declines in muscle mass and function in older adults are even predictive of their mortality. Despite the well-known health benefits of resistance training, few older adults engage in resistance-based exercise programs. The retirement age is a critical point. Although more time becomes available for activities other than work, this does not necessarily mean that more time is spent on sports. In some cases, the daily workload is also less intensive than during active working years. Although we already know what effects we can expect from adequately dosed strength training programs, most studies focus on the short- to moderate-term impact, with follow-ups mostly not extending beyond the 12-month mark. The study we discuss in this research examined two groups of individuals who had reached retirement age and followed moderate or heavy resistance training, compared to a control group. This study assessed the effects of their initial strength training four years later. Can heavy resistance training help with long-term muscle strength preservation?

Methods

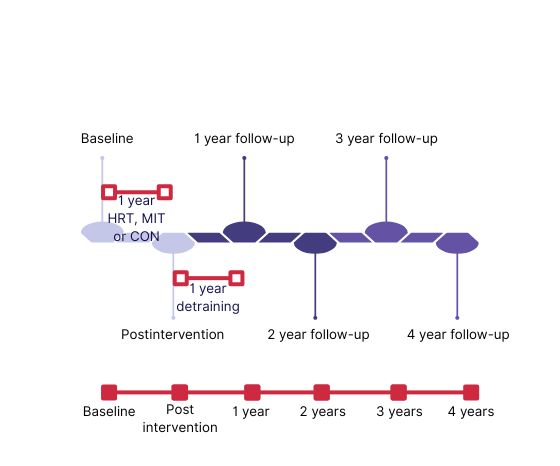

This paper is a long-term follow-up (4 years from baseline) of the LIve active Successful Ageing (LISA) parallel-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Denmark.

The original RCT included 451 older adults at retirement age, who were randomized after being stratified for sex, BMI, and chair-rise performance into:

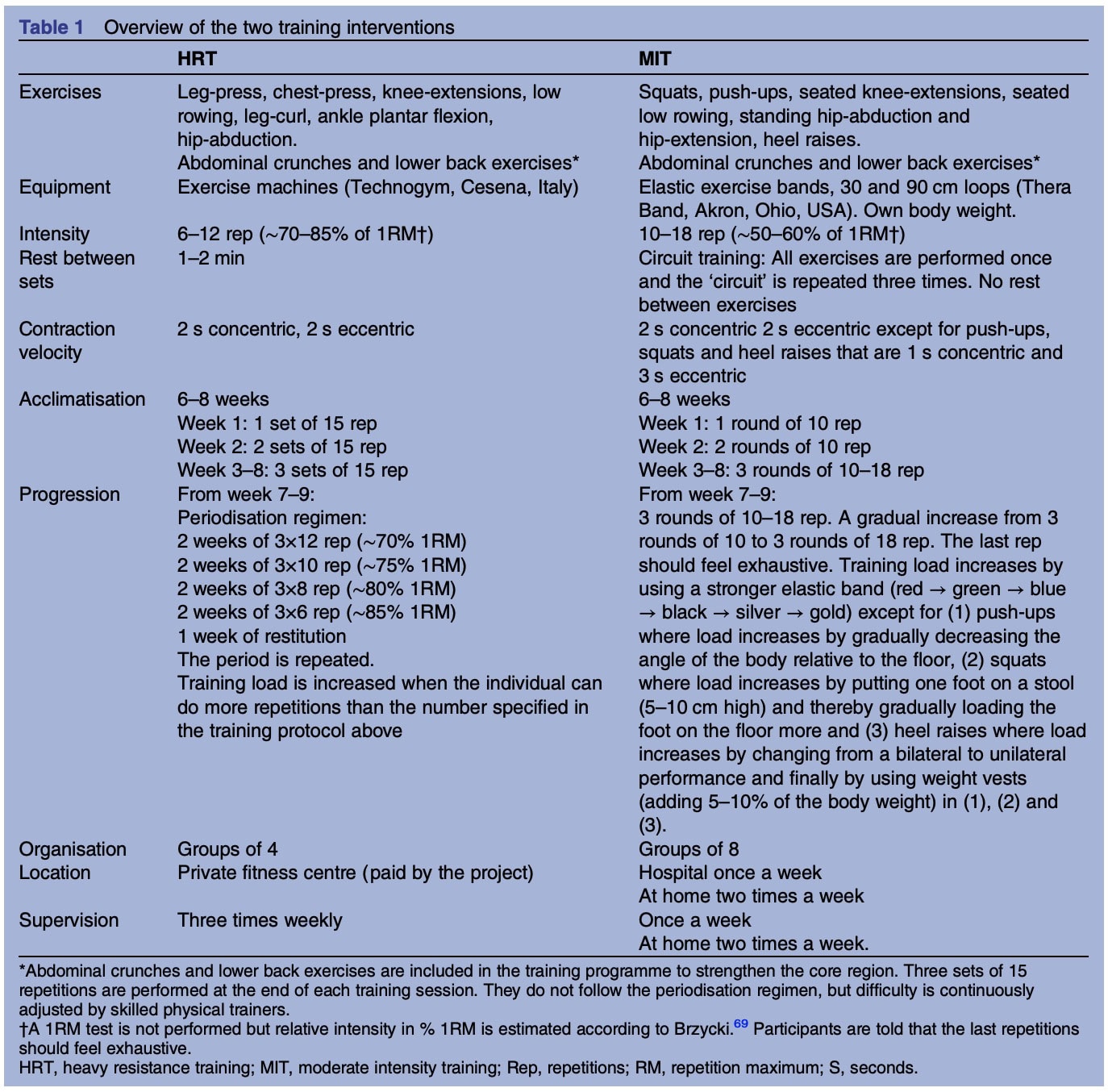

- Heavy resistance training (HRT)

- Moderate-intensity training (MIT)

- Control group (CON)

The group that was randomized to the HRT (heavy resistance training) program performed 1 year of supervised strength training three times a week in a commercial gym. The first 6-8 weeks served as a habituation phase. Afterwards, the participants performed machine-based full-body exercises in 3 sets of 6–12 reps at approximately 70%–85% of 1RM. Loads were individually prescribed according to the 1RM estimation using the Brzycki prediction equation, which is a method of submaximal testing.

The group that was prescribed MIT (moderate intensity training) engaged in a 1-year circuit training mimicking the HRT exercise selection. This group trained once per week at the hospital and twice per week at home. They performed the exercises using their body weight or with resistance bands. The exercises were performed in 3 sets of 10–18 reps at approximately 50%–60% of 1RM, with progressions made by increasing the loads of the resistance bands.

The control group was asked to maintain their habitual activity and were invited to regular cultural/social activities. They did not receive any specific “healthy behavior” counseling.

The outcomes were obtained at baseline, post-intervention (year 1), year 2, and year 4. The primary outcome was leg extensor power (expressed in W). Secondary outcomes included:

- Maximal isometric quadriceps torque (expressed in Nm)

- Body composition via DXA (lean mass, fat %, visceral fat estimated by scanner software)

- Vastus lateralis cross-sectional area (CSA) from thigh MRI; assessed by blinded assessors

- Daily steps via an accelerometer worn for 5 consecutive days

Results

The original RCT, published by Gylling et al. in 2020, included 451 older adults and randomized 149 to HRT, 154 to MIT, and 148 to the control group. The mean age of the included participants was 66 years at baseline.

The original RCT followed the participants for one year after completion of the 1-year supervised HRT, MIT, or CON program. There were three timepoints: baseline, postintervention, and 1-year follow-up. This RCT concluded that knee extensor muscle strength preservation was obtained during the follow-up (after 1 year of detraining) in people from the HRT group, since it was still 7% higher at the 1-year detraining follow-up (so at 1 year), compared to baseline.

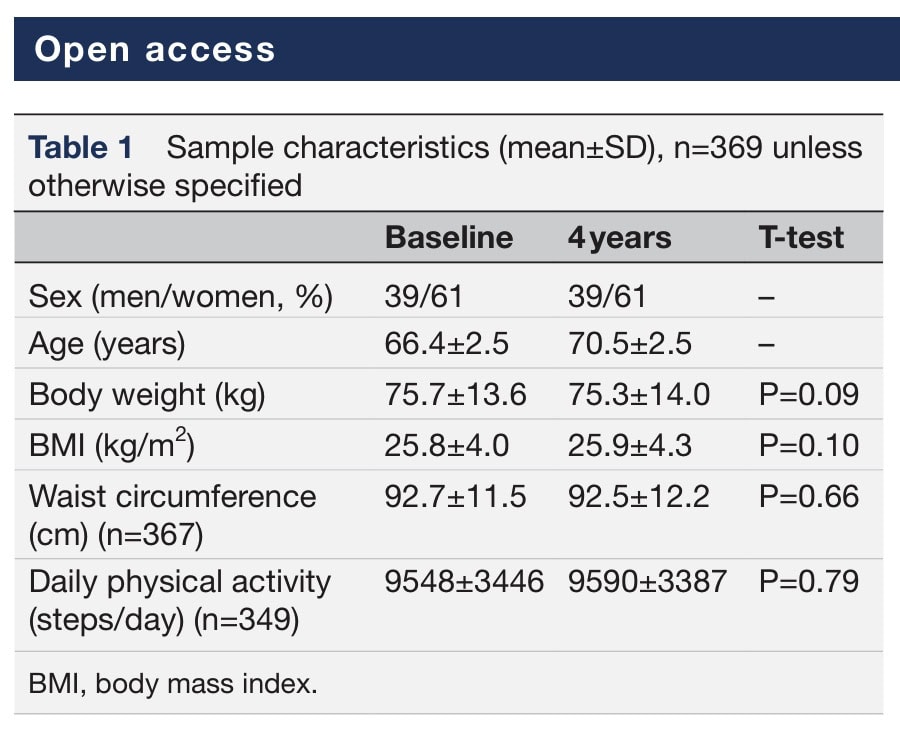

The current study investigated the effects at the fourth-year follow-up. At 4 years, 369 participants (128 from the HRT, 126 from the MIT, and 115 from the CON) presented for the follow-up measurements, and 82 participants were lost to follow-up, mainly due to lack of motivation or severe illness.

The authors noted that participants lost to follow-up had higher body weight, BMI, and waist circumference at baseline compared to those retained in the study at 4 years. Yet, there was no significant difference in response to the intervention at the first-year follow-up in those who stepped out of the study in the fourth year.

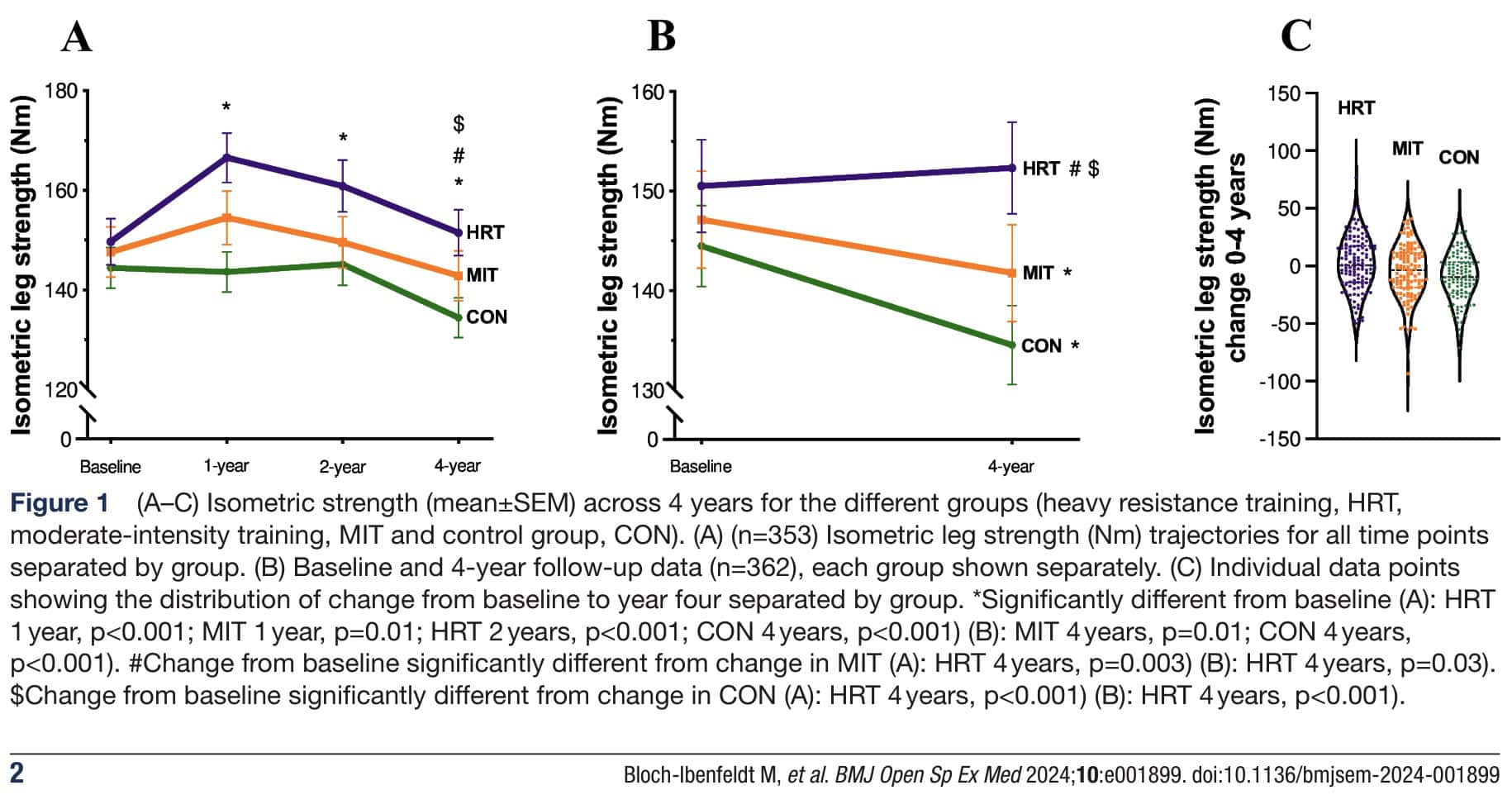

There was no difference in sample characteristics between the baseline and the 4-year follow-up, as shown in Table 1. At 4 years of follow-up, the primary outcome revealed that the isometric leg strength (secondary outcome) in the HRT group was unaltered from baseline. The MIT group demonstrated a decrease in muscle strength, which was not significant. The CON group had a significant decline in muscle strength at the 4-year follow-up.

Secondary outcomes

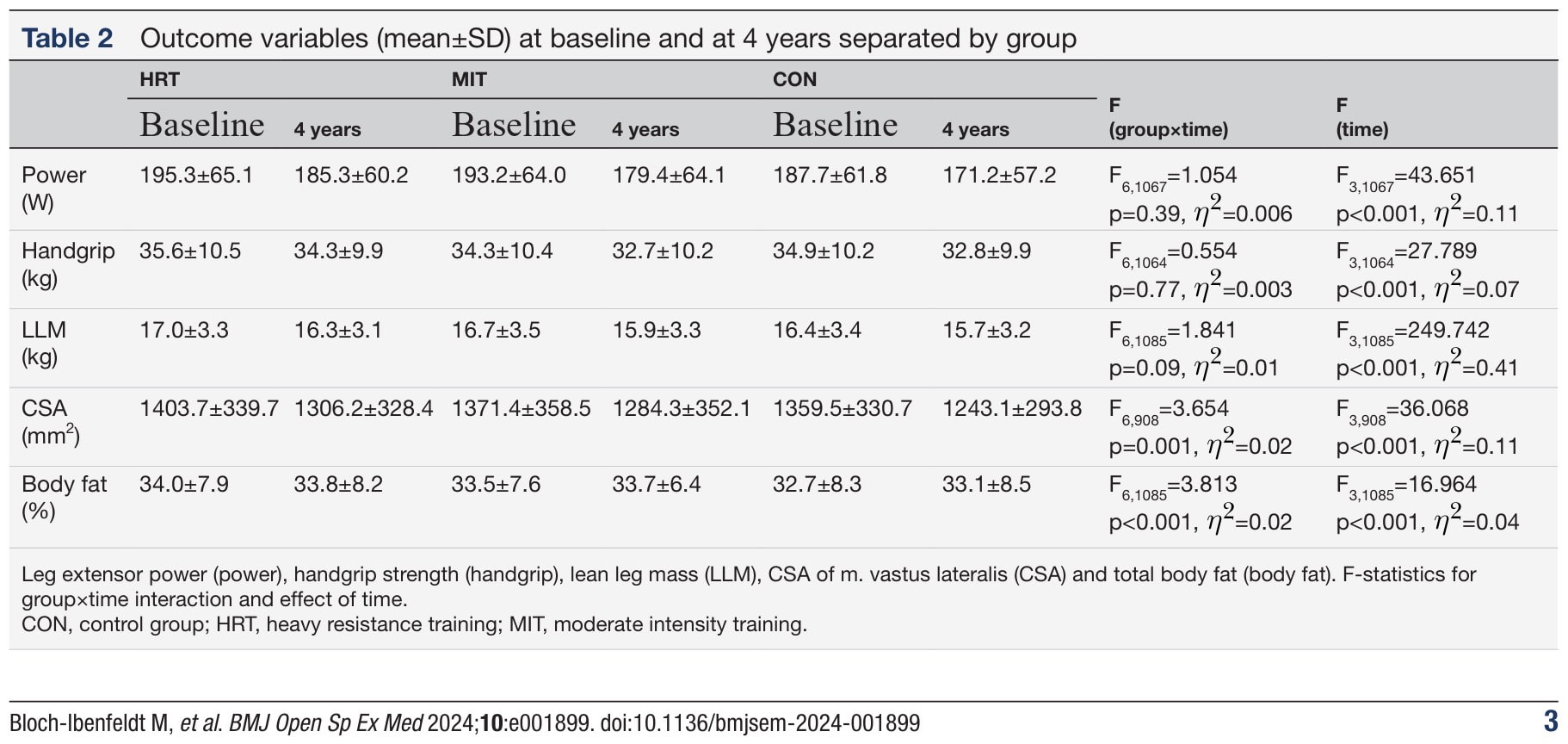

A significant group-time interaction was found in favour of HRT, which maintained its lean body mass (Baseline: 47.5±8.5 kg; 4 years: 47.3±8.3 kg). The lean body mass decreased in both MIT and CON groups. A significant group-time interaction was also found for visceral fat; it was maintained in both HRT and MIT over the 4 years. The CON group experienced an increase in visceral fat content. For leg extensor power (primary outcome), handgrip strength, and lean leg mass, there was a main effect of time (decreases over 4 years across all groups), but no significant group-time interaction effects or significant group differences in the change over 4 years. Handgrip strength, a measure of overall muscle strength, was not influenced by any of the training regimes.

Questions and thoughts

The HRT and MIT groups were exercising in two totally different settings. The first in a gym, the latter in a hospital, and at home. The home component in the MIT group may have also influenced adherence since they were requested to exercise twice per week at home and once a week at the hospital, while the HRT group was supervised at all times. Therefore, we must remain cautious that maybe the observed differences do not lie in the weights, but may also be partly attributable to the method of supervision. There was no report of an exercise diary to track adherence and compliance. Yet, the study stated that the participants received newsletters, personal test result overviews, and were invited to an information evening with general study results. Despite no adherence or compliance being mentioned, over the years, the study succeeded in achieving high attendance at the 4-year follow-up testing. Therefore, I would assume that the population may have sufficiently adhered to the program, despite this not being detailed in the paper.

When reading this paper, it is essential to keep in mind that the study included an already active population, characterized by a daily step count of 9548 ± 3446 steps. This may thus reflect a population with already good health behavior, which is aware of the benefits of exercise. Therefore, the drawn conclusions may not fully represent the whole elderly population. Despite the already high health behavior of the population, 80% of the included participants had at least 1 chronic medical disease. This enhances the generalizability of the findings to a broader population of elderly individuals, as the prevalence of chronic conditions increases with advancing age.

The current study can be seen as a motivating paper: it is never too late to start strength training, even at later ages. Equally important, being at retirement age does not equal functional decline: when you perform strength training for 1 year, it gives you a long-term advantage over several years, especially compared to those doing nothing (CON group), since 4 years later, you’ll see no decline in leg strength, whereas other groups in this study did show a significant decline.

Talk nerdy to me

The most appalling observation when reviewing this paper is the overreliance on a significant secondary outcome measure, isometric leg strength (expressed in Nm). As you can observe in the results and abstract, visually supported by Figure 1, the authors chose to build their paper around this secondary outcome measure that reached statistical significance, despite their primary outcome, leg extensor power (W) failing to reach that threshold of significance (Table 2).

At first glance, this looks like p-hacking, the overreliance on a secondary outcome in the absence of significance of the pre-specified primary outcome. This is a form of selective reporting bias that poses a threat to the validity of their findings. Yet, the authors in the present study took a crucial statistical step to protect the validity of their secondary findings by adopting a multiple comparisons correction (Bonferroni). By setting a very strict threshold of significance (p < 0.006, instead of the standard p < 0.05), they reduced the chance of making a type I error (false positive finding). Since this value is well below the conservative p < 0.006 threshold they set, the significant finding for isometric leg strength is considered statistically robust, even as a secondary outcome.

So, while the trial failed to prove its main hypothesis (maintenance of leg power), the extremely strong signal in the secondary outcome (maintenance of leg strength) suggests a genuine effect. The authors describe this as a biologically plausible mechanism, namely, the role of long-term neural adaptations in preserving force-generating capacity even as muscle mass may slightly decline. The authors suggest that neural adaptations are a primary driver of the long-lasting functional benefits.

The 1RM loads were individually prescribed based on a submaximal test and an equation to estimate the true 1 repetition maximum. Therefore, there may lie some error since the most reliable way to predict one’s 1RM is to do a direct 1RM test. Yet, it is time-consuming and not easy to perform for individuals not familiar with heavy resistance training, indicating the potential usefulness of predicting the 1RM based on a submaximal test.

In the original RCT, published in 2020, the detraining year was divided into two groups: STOP and CONTIN, defined by participants who ceased their program and those who maintained it, respectively in the period from post intervention to the 1-year follow-up. The 2020 abstract states:

“Out of all the improvements obtained after the 1-year training intervention (post-intervention), only knee extensor muscle strength in HRT was preserved at 1-year follow-up (p < 0.0001), where muscle strength was 7% higher than baseline. Additionally, the decrease in muscle strength over the second year was lower in CONTIN than in STOP with decreases of 1% and 6%, respectively (p < 0.05). Only in CONTIN was the muscle strength still higher at 1-year follow-up compared with baseline with a 14% increase (p < 0.0001). The heavy strength training induced increase in whole-body lean mass was erased at 1-year follow-up. However, there was a tendency for maintenance of the cross-sectional area of m. vastus lateralis from baseline to 1-year follow-up in HRT compared with CON (p = 0.06). Waist circumference decreased further over the second year in CONTIN, whereas it increased in STOP (p < 0.05).”

The current study did not mention anything about those 2 distinct STOP and CONTIN groups, making it unclear whether these results are seen in the people who continued training, in those who did not, or in both.

Take-home messages

Physiotherapists routinely prescribe resistance training to counter age-related declines in muscle mass and function, but most trials only tell us what happens during training and shortly after it ends. This study was important because it tested whether a single, structured year of supervised heavy resistance training (HRT) around retirement age can “buy” long-lasting preservation of strength years later, compared with moderate-intensity training (MIT) or no exercise intervention (CON).

For well-functioning adults around retirement age, committing to one year of a heavy, supervised resistance training program can protect against the age-related decline in leg strength for at least the next three years, outperforming both moderate-intensity exercise and no formal exercise. The heavy resistance training is a viable way for long-term muscle strength preservation. It also helps prevent the increase in visceral fat that was seen in the non-exercising control group.

Reference

100% FREE POSTER PACKAGE

Receive 6 High-Resolution Posters summarising important topics in sports recovery to display in your clinic/gym