Physical Activity and Musculoskeletal Pain Prevention

Introduction

As physiotherapists, we are confronted with people presenting with musculoskeletal conditions, and we aim to alleviate their symptoms using a variety of exercises and treatments. Ultimately, we aim for secondary prevention, helping that individual reach a level of resilience. But what if we could work on primary prevention? This study examined the associations between physical activity levels and the risk of developing musculoskeletal conditions, contributing important insights into Activity and Musculoskeletal Pain Prevention. In this research review, we aim to summarize their conclusions and what they may mean for your practice.

Methods

This study utilizes the All of Us Research Program, one of the largest U.S. health databases, to address a gap that physiotherapists have long recognized: Is more objectively measured physical activity associated with a lower risk of developing musculoskeletal pain?

Specifically:

- Does more stepping reduce risk?

- Do moderate or vigorous activity intensities matter?

- Are certain regions (neck, low back, hip, knee) affected differently?

- Are these relationships consistent across age, sex, and sedentary time?

To examine these relationships, the authors conducted an observational cohort study using wearable device data (Fitbit) linked to electronic health records from adults enrolled in the All of Us Research Program database.

Participants were adults (≥18 years) who shared both Fitbit and electronic health records data, had at least 6 months of Fitbit monitoring with ≥10 hours/day and ≥10 valid days/month, had no baseline neck, low-back, hip, or knee pain, and had at least 12 months of Fitbit data before any first recorded pain diagnosis to minimize reverse causation.

Activity measures from the Fitbit were summarized monthly:

- Daily steps

- Lightly active minutes (1.5–3 METs)

- Fairly active minutes (3–6 METs, >10 min bouts)

- Very active minutes (≥6 METs or ≥145 steps/min, >10 min bouts)

The first occurrence of neck, low back, hip, or knee pain documented in the electronic health record of the participant was used for analysis.

Results

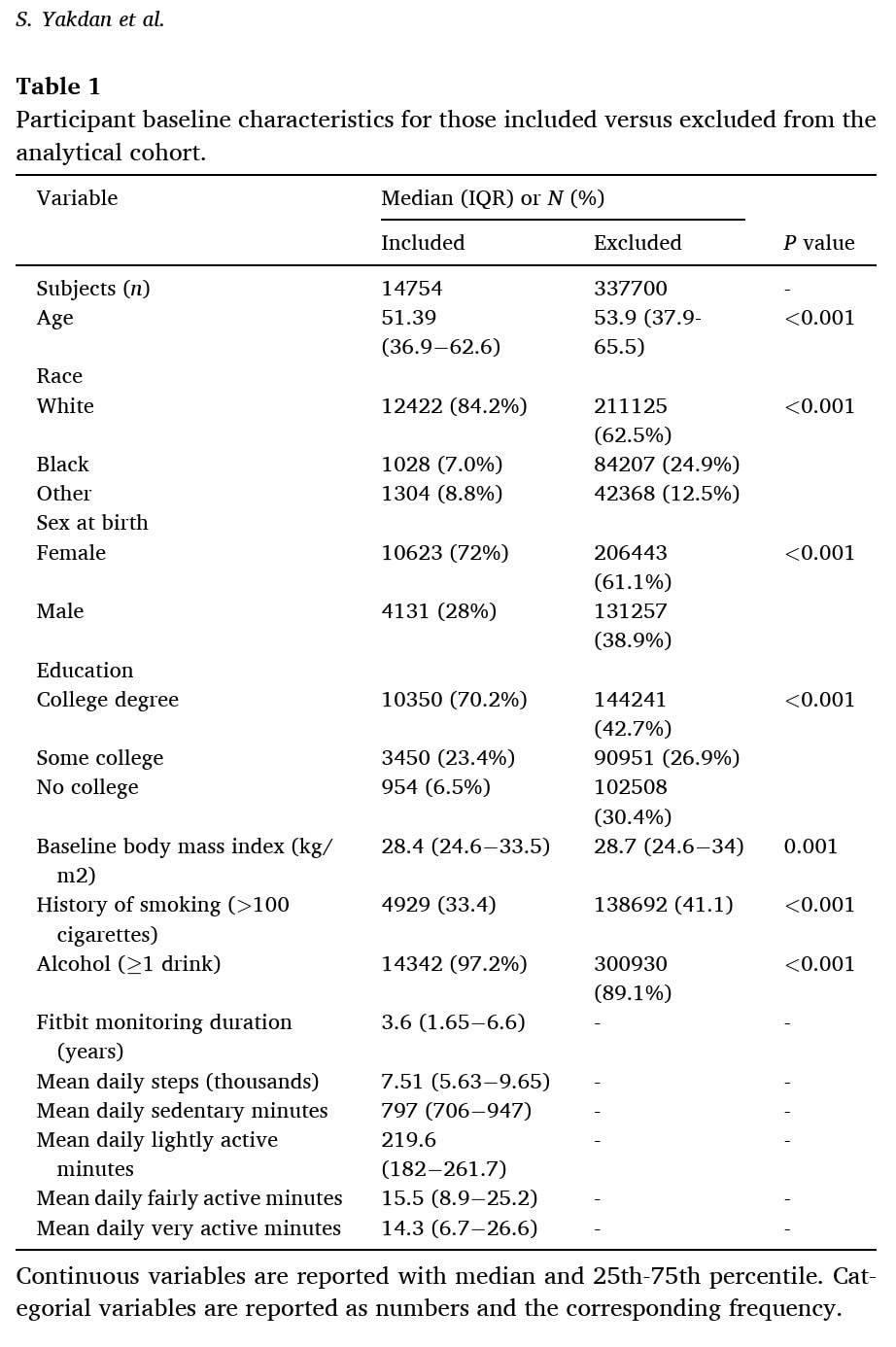

To study the relationship between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain prevention, 14,754 participants were included. They had a median age of 51.3 years and were predominantly female (72%) and white (84.2%). The study recorded a total of 796 cases of low-back pain, 144 cases of neck pain, 1,362 cases of hip pain, and 1,754 cases of knee pain during a median follow-up period of 3.6 years.

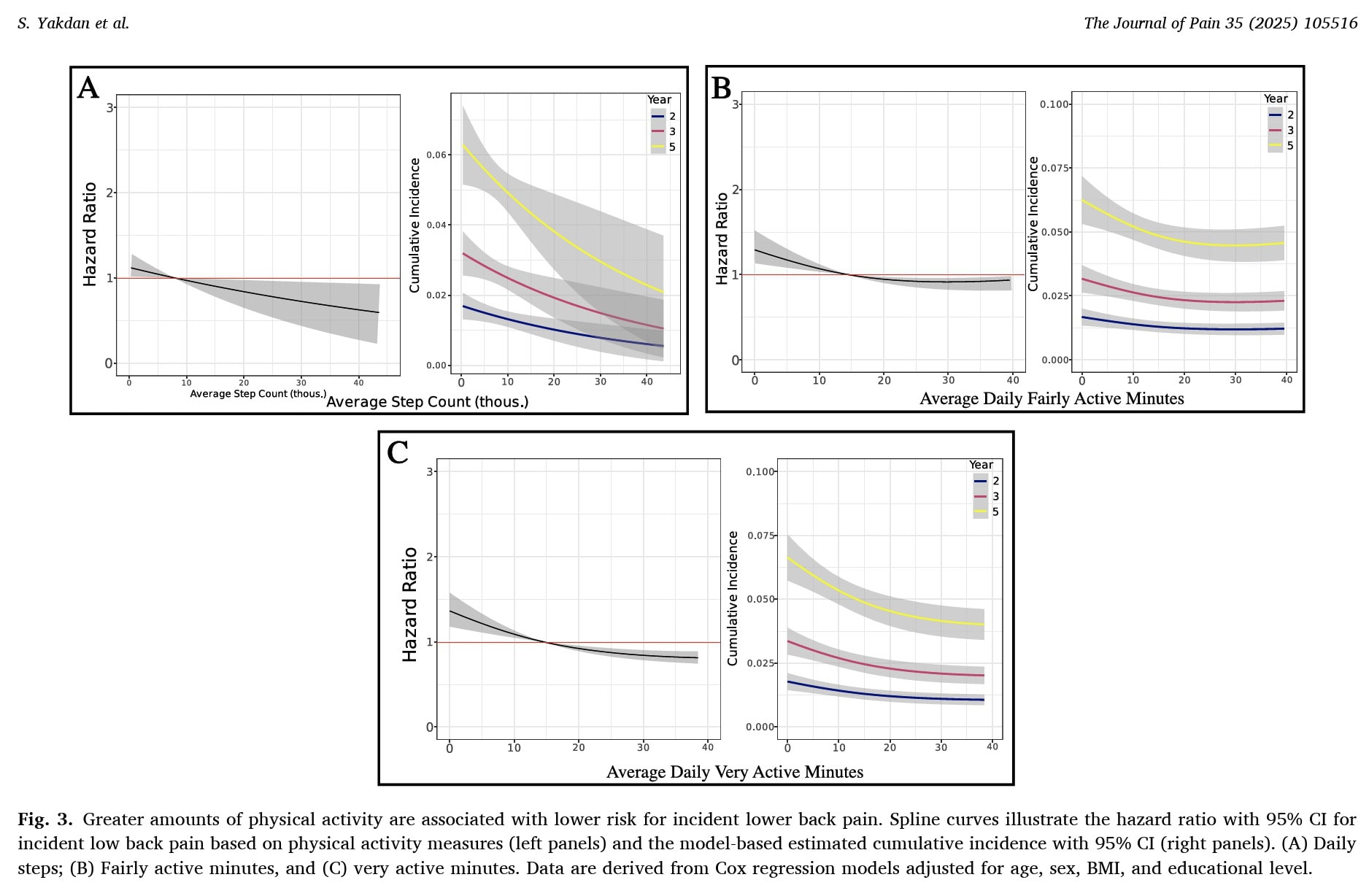

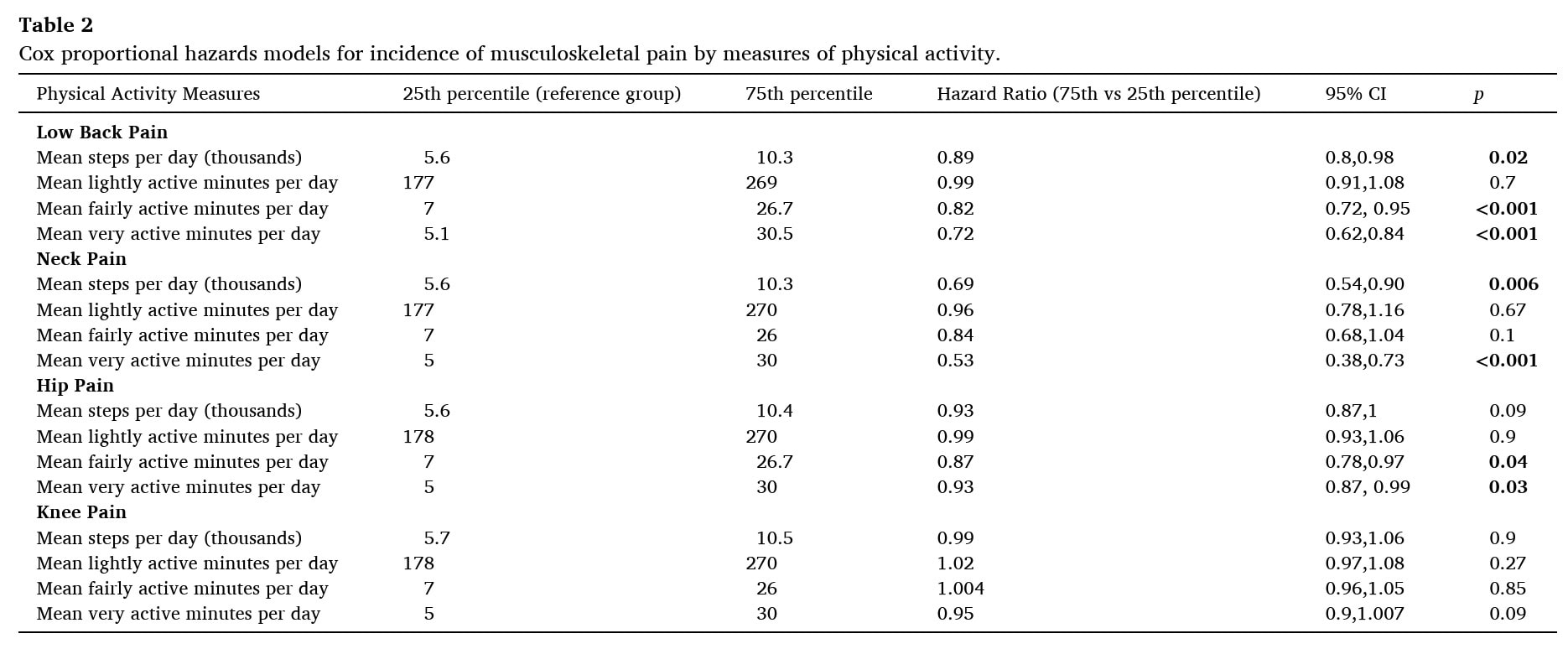

The analyses demonstrated that higher levels of physical activity were consistently associated with a reduced risk of developing several forms of musculoskeletal pain.

- For low-back pain, participants with higher daily step counts (75th percentile vs. 25th percentile) had a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 0.89 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.98), corresponding to an 11% reduction in risk. Those engaging in greater amounts of moderate and vigorous activity experienced even greater reductions in risk (HRs of 0.82 and 0.72, respectively). Light activity showed no meaningful association.

- A similar protective pattern emerged for neck pain: individuals taking more daily steps (75th percentile vs. 25th percentile) had a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 0.69 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.90), corresponding to a 31% lower risk of developing neck pain. More mean time of vigorous activity was strongly protective (HR 0.53; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.73), while light and moderate activity were not significantly associated.

- Regarding hip pain, moderate and vigorous activity levels were both significantly associated with reduced risk, demonstrating HRs of 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.97) and 0.93 (95% CI 0.87 to 0.99), respectively. But regarding hip pain, daily steps alone did not reach statistical significance.

- In contrast, none of the physical activity measures (including step count, light activity, moderate activity, or vigorous activity) were associated with the incidence of knee pain, suggesting a different underlying relationship between activity and knee joint symptoms compared to the spine or hip.

Questions and thoughts

Activity and Musculoskeletal Pain Prevention research is influenced by a key limitation of this study: it included mainly well-educated, white, female participants. The fact that they already wore a wearable activity tracker (Fitbit) when they were enrolled may indicate that these individuals were already highly conscious about their health and fitness. It is plausible to assume that, because they used such a device, they were already moderately active, or at least aware of the benefits of movement on their health. This study would ideally be reproduced in more diverse populations to better generalize the findings to the broader public.

Another key aspect to remember is that the health conditions studied here were captured using an electronic health record database. This means that the information on the occurrence of the studied musculoskeletal conditions was derived from medical healthcare systems. You’ll certainly understand that not everyone experiencing a musculoskeletal condition will seek medical advice. It also raises questions about the accuracy of determining “true” pain onset. Many individuals manage new symptoms independently and may not seek medical care until pain becomes persistent or disabling. As a result, the dataset may overrepresent more severe cases while missing early symptom onset or milder presentations. This has implications for interpreting the timing and direction of the activity–pain relationship.

Further, it is unknown whether Fitbit’s activity categories truly capture the mechanical load relevant to musculoskeletal pain. The device classifies “moderate” and “vigorous” activity using MET-based thresholds, which reflect cardiovascular effort rather than joint stress or movement quality. For physiotherapists, however, the mechanical load on the spine, hip, and knee is often more clinically meaningful than metabolic intensity. This raises the question of whether the protective effects observed in this study would differ if activity were categorized based on biomechanical loading rather than metabolic demand.

Strength training and muscle mass were not measured in this study. While stepping and general physical activity are valuable, muscle strength is a well-established protective factor against musculoskeletal pain. Without accounting for resistance training or baseline strength levels, it is difficult to determine whether the observed associations reflect the benefits of activity alone or whether stronger, more conditioned individuals simply tolerate higher activity without developing pain.

Occupational exposure is another unmeasured factor that could have influenced the results. Daily steps accumulated during physically demanding jobs involve very different mechanical loads compared to recreational walking. This is known as the physical activity paradox. Without distinguishing occupational from leisure-time activity, it is difficult to know whether the observed associations reflect the benefits of voluntary movement or the consequences of repetitive occupational strain.

Finally, it remains unclear whether physical activity itself is protective or whether it simply reflects broader aspects of good health and lifestyle. More active people often have better general health, sleep patterns, and stress levels, all of which are known to influence musculoskeletal pain risk. If this is the case, physical activity may act as a marker of overall health rather than a direct causal factor, and the protective effect seen in this study may partially reflect these unmeasured variables.

Talk nerdy to me

This is not the first study measuring the associations between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain prevention. Yet, it tackles some limitations that existing studies on this topic encountered, such as:

- Reliance on self-reported activity introduces biases (recall bias, social desirability bias).

- Monitoring physical activity only for short periods (days–weeks), making long-term associations unclear.

- Focusing on rehab or post-surgical outcomes, not whether activity prevents musculoskeletal pain in otherwise pain-free individuals.

- Failure to capture real-world, continuous physical activity patterns makes it difficult to study activity as a true risk factor.

To counter these methodological limitations of older research, the authors used time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models, meaning:

- Activity was tracked over time, not as a single baseline value.

- Monthly activity values were allowed to change, reflecting real life.

- Models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and education.

The hazard ratios compared the 75th vs the 25th percentile of each activity metric. This was done because this reflects a realistic difference between someone who is less active and someone who moves more in everyday life. It avoids extreme cases, either high up or at the low end of the spectrum, and instead focuses on meaningful changes. For example, increasing daily steps from roughly 5,600 (25th percentile) to 10,300 (75th percentile) is an understandable goal that patients can actually work toward. This makes the results clearer and more useful for clinicians.

Finally, the observational design cannot prove causation, and the study may miss some important confounders, such as occupation, psychosocial factors, and prior minor injuries.

Take-home messages

This study demonstrated associations between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain prevention. People who move more, especially at moderate and vigorous intensities, show a lower risk of developing neck, low-back, and hip pain. The step count helps, but higher-intensity activity appears to provide additional protective benefit. For the knee, the study found no association between any form of physical activity (steps, light, moderate, or vigorous) and the development of knee pain, meaning activity neither increased nor reduced knee pain risk in this cohort. Wearable devices can offer clinically meaningful insights into long-term activity patterns and musculoskeletal pain risk.

Reference

100% FREE POSTER PACKAGE

Receive 6 High-Resolution Posters summarising important topics in sports recovery to display in your clinic/gym.