Medial Epicondylalgia / Golfer's Elbow | Diagnosis & Treatment

Medial Epicondylalgia / Golfer’s Elbow | Diagnosis & Treatment

Introduction & Epidemiology

Medial Epicondylalgia, better known as Golfer’s elbow is a tendinopathy of the common wrist flexor and pronator muscle origin at the medial epicondyle. In comparison to its “big brother” tennis elbow, Golfer’s elbow is 4 to 7 times less common. A study by Leach et al. (1987) even mentions that LE is 7-10 times more common than medial epicondylalgia. In a study of the US military, the incidence rate for golfer’s elbow was 0.81 per 1000 person-years (Wolf et al. 2010).

Medial Epicondylalgia, better known as Golfer’s elbow is a tendinopathy of the common wrist flexor and pronator muscle origin at the medial epicondyle. In comparison to its “big brother” tennis elbow, Golfer’s elbow is 4 to 7 times less common. A study by Leach et al. (1987) even mentions that LE is 7-10 times more common than medial epicondylalgia. In a study of the US military, the incidence rate for golfer’s elbow was 0.81 per 1000 person-years (Wolf et al. 2010).

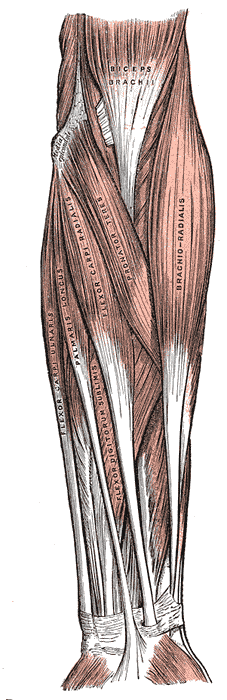

Medial epicondylalgia is thought to result from overuse of the common flexor-pronator tendon complex (including the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and the flexor carpi ulnaris). Excessive valgus stress has been implicated in the development of medial elbow pain as well (Mishra et al. 2014).

The term epicondylitis was questioned over time as histological studies have failed to show inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) in the affected tissue. These studies showed fibroblastic tissue and vascular invasion that lead to the term ‘tendinosis’. This rather defines a degenerative process characterized by an abundance of fibroblasts, vascular hyperplasia, and unstructured collagen (De Smedt et al. 2007)

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Elbow pain is the presenting complaint in patients with epicondylalgia. Patients often tend to ignore early symptoms and visit a health professional rather late. History describes either trauma or repetitive unilateral tasks at work, during ADLs, or sports with a gradual onset of pain (Orchard et al. 2011). The pain is usually worse with activity and relieved by rest and may or may not radiate down the forearm along the wrist flexor muscles. On top of that, patients might experience weakness in the hand and difficulty carrying items (Pitzer et al. 2014).

Although medial and lateral epicondylitis are similar, a study by Pienimäki et al. (2002) compared the two conditions in two chronic groups and found that the reduction in grip strength is less severe in medial epicondylalgia nd that pain is more widespread in lateral epicondylalgia.

Examination

For a thorough assessment and differential diagnosis, the cervical spine, shoulder, elbow, and wrist should be examined in both conditions. Patients with medial epicondylalgia present with tenderness at the origin of the common flexor-pronator tendon of the forearm, at or just distal to the medial epicondyle.

In the literature, only two orthopedic tests are described to assess medial epicondylalgia. Watch the videos below to learn how to perform them:

The second test, Polk’s Test, described by Polkinghorn et al. (2002) stresses both the lateral epicondyle in phase I of the test, as well as the medial epicondyle in the second phase of the test:

WATCH TWO 100% FREE WEBINARS ON SHOULDER PAIN AND ULNA-SIDE WRIST PAIN

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

As literature about medial epicondylalgia is scarce, the treatment recommendations are based on general literature about tendinopathy and from transferring knowledge about tennis elbow to Golfer’s elbow. First of all: Tendons don’t get better with rest. While you might get away with general rest in case of reactive tendinopathy, not loading your tendon will never help with a tendon in the stage of late disrepair or degeneration as it further decreases the tendon’s capacity to take load. In our experience, most patients involved in overhead or racket sports report pain improvement when they stop their sport but actually experience more pain and disability when they try to pick up their sport again after the break.

Furthermore, recent research has shown that the inflammation seen in tendons is not the classical inflammation we see in other tissues of the body. On top of that, the literature shows that we are not able to change the pathological part of a tendon. That’s where the expression “change the donut, not the hole” comes from. For these reasons, treatment options directed at decreasing inflammation or at changing the pathological part of the tendon don’t make sense.

Let’s now look at a possible rehab program that does make sense:

Decrease aggravating high and fast load activities:

Like in other tendons, high and fast load activities – meaning that the tendon has to store and release energy quickly – are the main driver behind tendon overload. This is also why golfer’s elbow is often seen in overhead athletes or racket sports that make use of the elastic action of the tendon at the elbow and wrist when throwing or hitting a ball. While it’s not necessary to stop all high and fast load activities, it is recommended to reduce volume – so either frequency, duration, or reps and intensity – to a level that the patient’s pain aggravation settles within 24 hours after the activity. So in my personal case, I reduced the number of times I played per week from 4 to 2 or 3 and tried to avoid playing on consecutive days. Furthermore, I tried not to play matches in order to avoid serving. By doing this, I was able to break the downward spiral of my elbow getting worse and worse until the pain stayed at a stable level at least.

Adjunctive options

Some patients have positive experiences with the use of braces, kinesiotaping, dry needling, massage, or ice. While these options can be added based on patient and therapist preference, be aware that none of these options will increase the tendon’s capacity to bear load in the mid and long term. In my personal experience, the use of ibuprofen has a positive short-term effect on tendon pain and stiffness. Literature has also shown that it inhibits the expression of key ground substance proteins for tendon swelling in in-vitro tendon preparations. At the same time, you don’t want to end up being dependent on medication for more than a week or two that can possibly cause stomach problems.

Early Rehab: Heavy and slow resistance exercises

Next to the wrist flexors, you also want to target the pronator teres whose tendon also originates from the medial epicondyle and which is also often affected. For this muscle and tendon, we are performing pronation with a head-heavy object like a hammer, tennis racket or broom. You can increase the resistance by adding more weight to the broomstick. Again, perform around 3 sets with 5-15 repetitions with a cadence of around 3 seconds and tolerable pain. Progress the exercise by doing more reps or by increasing the leverage or the weight.

Targeting the shoulder

A quick shout-out at this point to our colleagues from E3 rehab who have found 2 studies by Elmaboud et al. (2016) and Nabil et al. (2019) showing that shoulder external rotation, extension, and abduction peak torques are decreased in patients with tennis and golfer’s elbow. If the shoulder muscles are not able to absorb load during overhead or racket sports, stress might be passed on to the distal joints of the upper joint. Therefore, it might make sense to include exercises that target external shoulder rotation like cable pulley, abduction exercises like lateral raises, and shoulder extension exercises like pullovers.

Ulnar nerve glidesAccording to Donaldson et al. (2013), coexisting ulnar neuritis can be present in up to 50% of cases suffering from medial Epicondylalgia. This means that we will not only have to focus on the tendons and muscles of the wrist flexors and forearm pronators but also on the ulnar nerve. Click on the info button in the top right corner to learn how to examine the ulnar nerve.

In order to target the ulnar nerve, you can perform ulnar nerve sliders and tensioners. We recommend starting with the less provocative sliders and moving on to tensioners as soon as sliders are tolerated well by the patient. To perform the slider at home, the patient is asked to abduct their shoulder, extend their fingers and wrists, pronate their forearm, and flex the elbow. Then the hand is moved towards the head while moving the head and neck to the ipsilateral side at the same time in an attempt to move the ulnar nerve proximally. To move the ulnar nerve distally again, reverse both movements.

To perform a tensioner, the same upper limb movements are performed now only the head is moved contralaterally. There is no strict number of repetitions. We generally recommend doing around 10 to 20 repetitions several times per day on a daily basis.

Do you want to learn more about elbow conditions? Then check out our blog articles and research reviews:

- 7 crucial facts you didn’t know about tendons

- Isometrics in tendinopathy – a wonder weapon to decrease pain?

References

Orchard, J., & Kountouris, A. (2011). The management of tennis elbow. Bmj, 342.

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Increase your confidence in assessing and treating the Stiff Shoulder, Elbow & Wrist

What customers have to say about this course

- Senne Gabriëls30/12/24A complete understanding of elbow pathologies and management Very broad explanation of al the possible differential diagnosis and nice comprehensive management strategies with a big catalogue of exercises.Barbara14/12/24Really good Like always, perfect support to learn at your own rythm.

clear explanations and evidence based.

Thank you - Mika Tromp06/12/24Nice course! Explained the difference between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis nicely. Learned a few new things to use in clinical reasoning as well.Anneleen Peeters03/04/24Upper Limb Focus - The Wrist & Hand GREAT CONTENT!

Very happy with the way the course is presented; part videos, text and quizzes.

Great teachers, great refresher on the anatomy. - Dominik Meier01/04/24The Upper Limb Focus: Wrist & Hand CLINICALLY RELEVANT AND VERY WELL STRUCTURED COURSE!

This course is clinically relevant and very well structured. The wrist and hand is a very complex topic which has been described in a comprehensive and logical way. I can really recommend it. I like the theory and especially the cases. Thank you!Lieselot Longé29/12/23Upper Limb Focus - The Stiff Shoulder GOEDE CURSUS OM THUIS OP EIGEN TEMPO TE BEKIJKEN!

Dit is de 2de cursus die ik volg via physiotutors en net als de vorige cursus vond ik ook deze zeer leerrijk. Je krijgt dankzij deze cursus nieuwe inzichten in de behandeling van een stijve schouder. Er worden behandeltechnieken (o.a. mobilization with movement) getoond via video’s. Het leuke is ook dat je de cursus op je eigen tempo thuis kan volgen en na het afronden van de cursus kan je er nog steeds naar terug grijpen. Ik kijk ernaar uit om nog andere cursussen van physiotutors te ontdekken en raadt het ook anderen ten zeerste aan!. - Mieke Versteeg01/12/22Upper Limb Focus - The Elbow Inhoudelijk kwalitatief zeer hoogstaand.

Nog betere vertaling naar Nederlands zou toegevoegde waarde zijn.

Hulp per mail/telefonisch op ieder moment aanwezig/bereikbaar.