Recognizing Lumbar Facet Joint Pain in Practice - Recommendations from a Delphi Expert Consensus

Introduction

Pain in the lumbar spine gets classified based on the presence or absence of pathological findings into specific and nonspecific low back pain, respectively. As only a minority is classified as specific low back pain, and around 90% gets labeled nonspecific, it seems quite easy to classify the patient into one of these categories. Recently, Abe et al. noted that pain arising from the lumbar facet joints is often overlooked and misdiagnosed as nonspecific low back pain, despite a specific structure contributing to this pain. For pain originating from the lumbar facet joints, a specialized diagnostic pathway exists through facet blocks to pinpoint the exact source of someone’s pain. Yet, these require access to specialized care, and as the majority of these patients get labeled with “nonspecific low back pain”, there is no referral to specialized care, despite good outcomes can be achieved through localized facet joint denervation in someone having lumbar facet joint pain. Therefore, the current study wanted to develop a practical approach for use in generalist practices that does not require specialized investigations for recognizing lumbar facet joint pain.

Methods

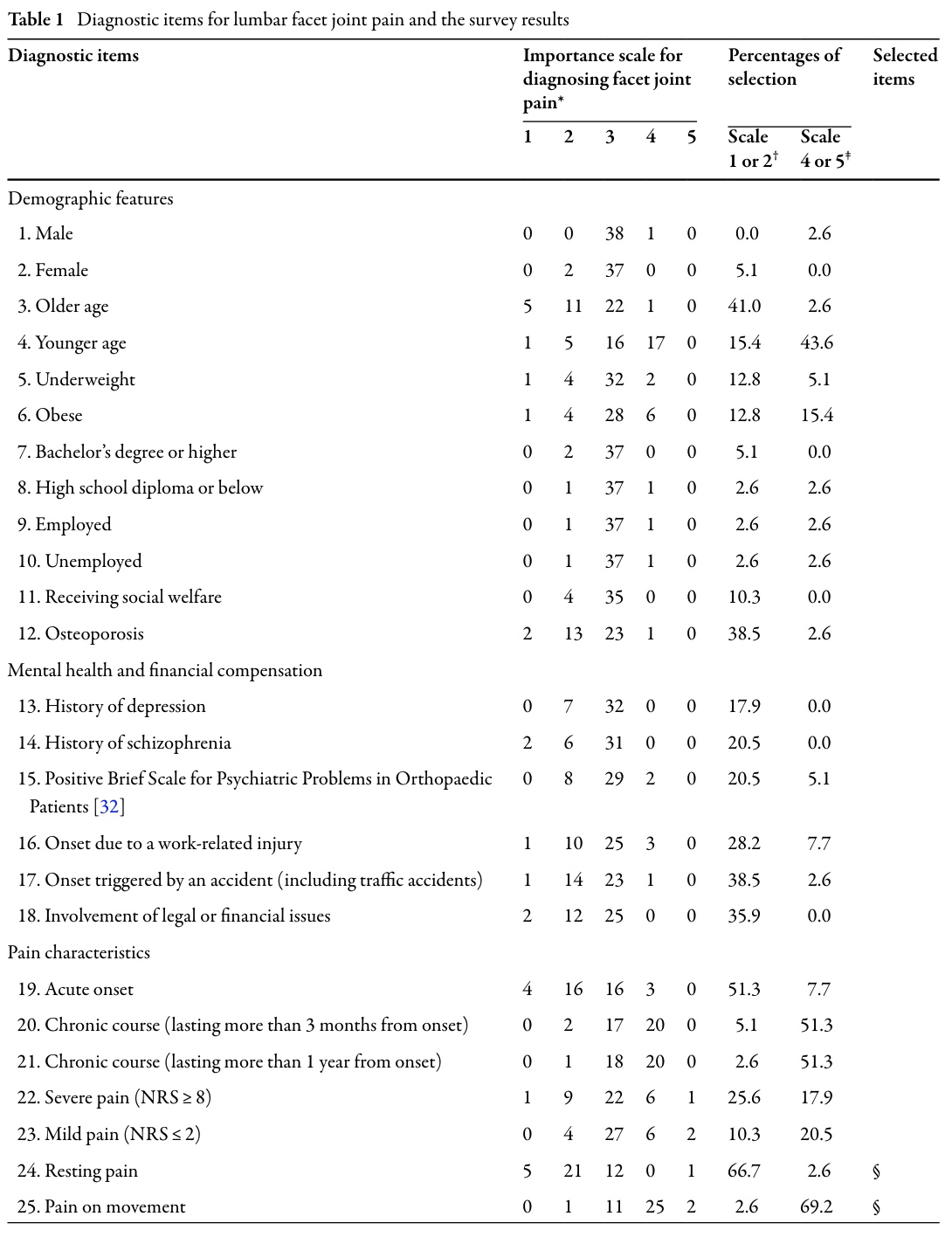

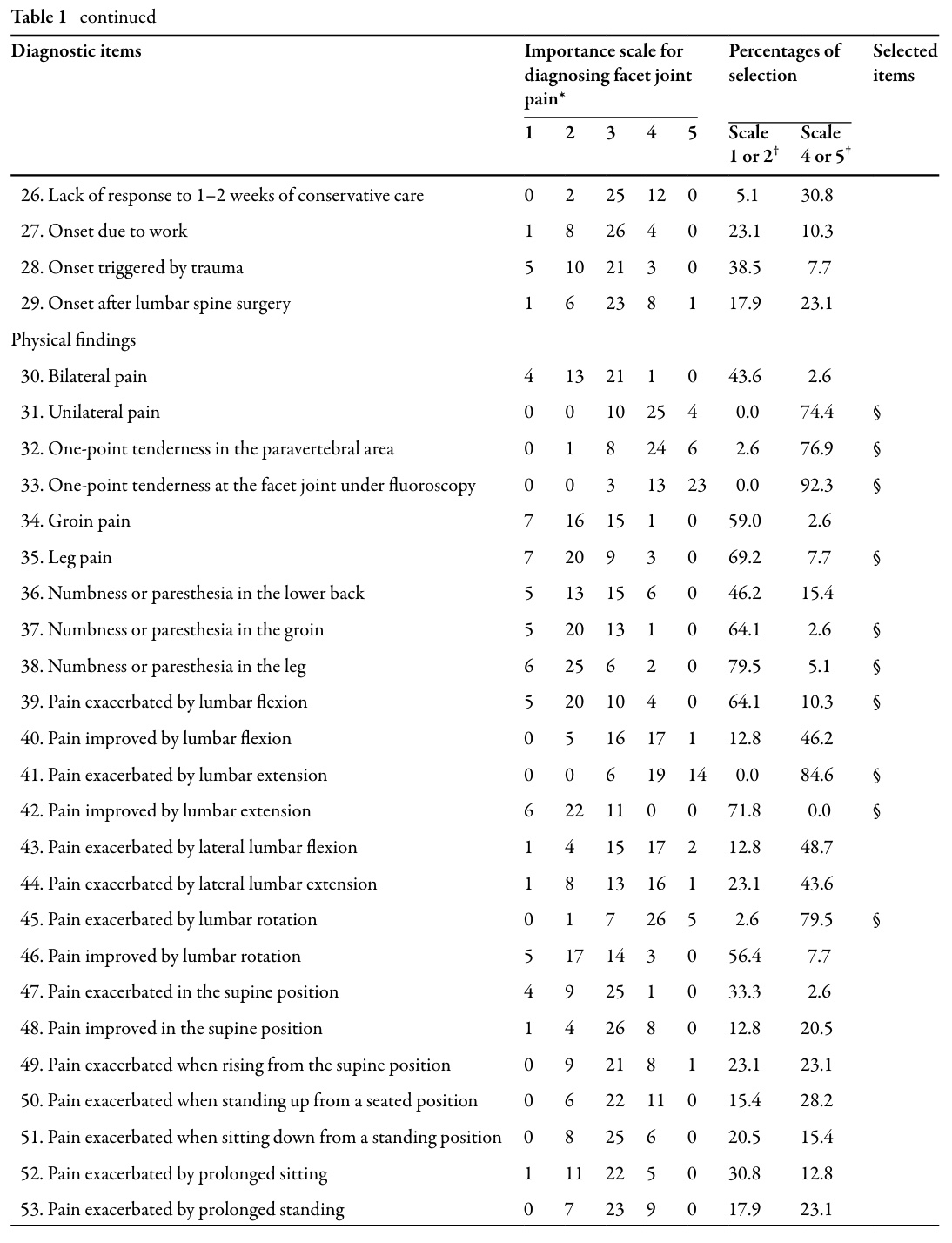

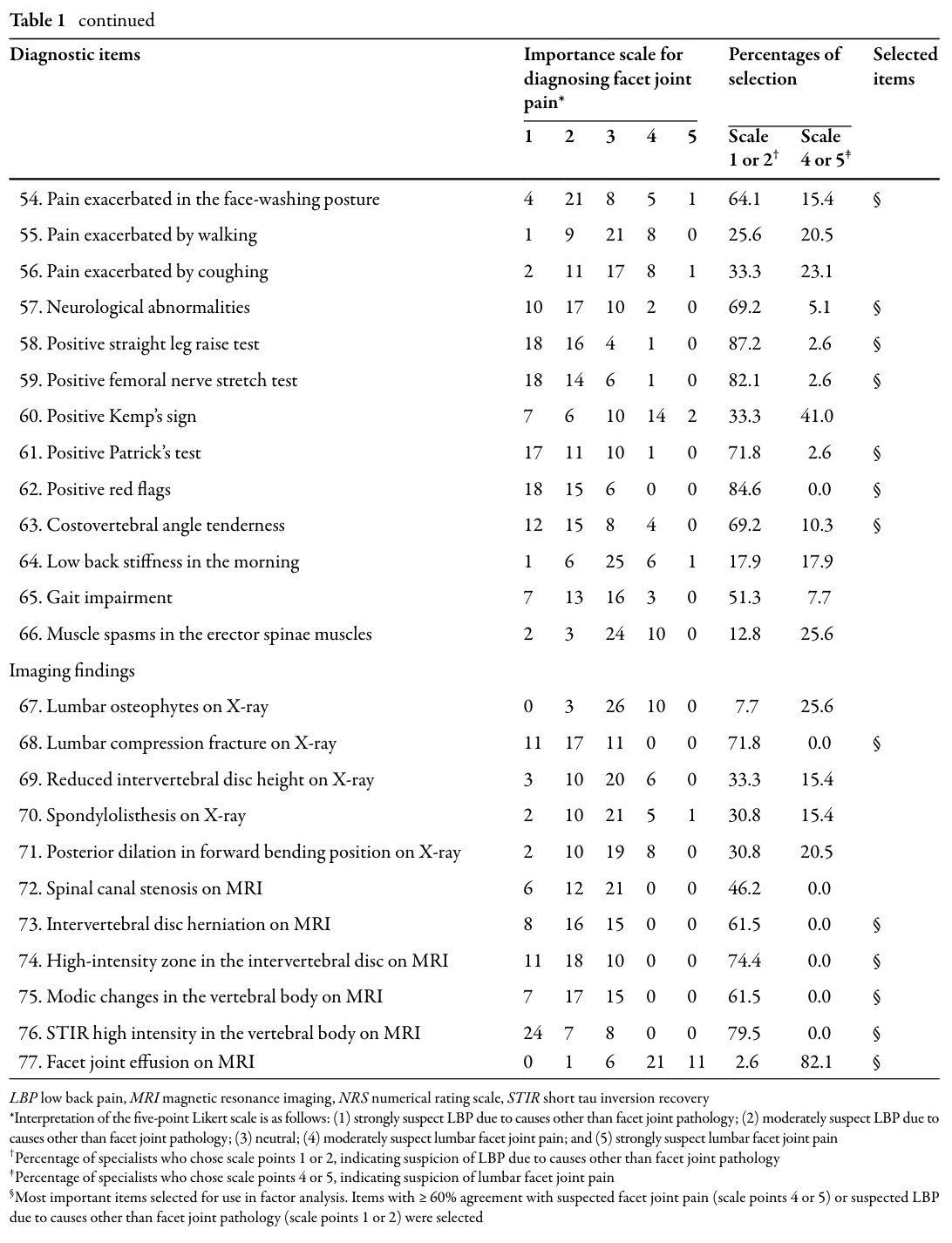

Abe et al. 2025 used a structured, multi-step approach. The first step was a literature search and extraction of diagnostic items. A PubMed search (2000–2023) identified 2682 papers; from the eight eligible studies, 71 diagnostic items describing signs/symptoms of facet pain were extracted. Committee members then added six clinically relevant items (e.g., Patrick’s test, red flags, disc herniation, Modic changes), bringing the total to 77 items.

Following the extraction of these possible diagnostic indicators from the literature, 39 orthopedic spine surgeons were asked to rate each of those on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly suspect other causes” to “strongly suspect facet joint pain.” Items were retained if ≥60% of surgeons rated them as:

- indicative of facet joint pain (scores 4–5), or

- indicative of alternative pathology (scores 1–2).

This filtering process reduced the list from 77 to 25 items considered diagnostically meaningful in real-world practice.

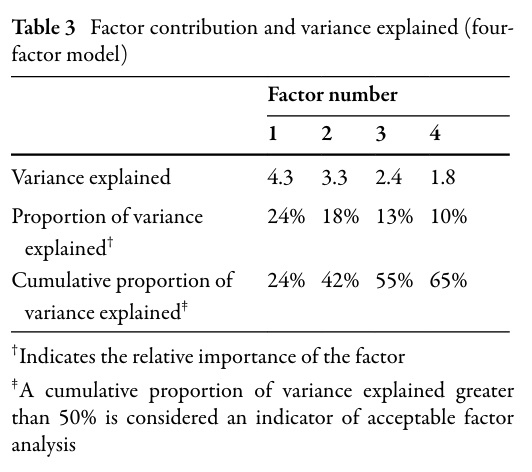

In the second step, these 25 diagnostic items were introduced into a factor analysis. This is a way to group the 25 items into underlying clinical domains. The committee compared 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-factor models, achieving 100% consensus that a 4-factor model was most clinically interpretable, explaining 65% of the variance (Table 3).

The resulting factors were:

- Factor 1: Neurological symptoms in the leg/groin indicative of neuropathic pain

- Factor 2: Imaging findings suggesting non-facet causes

- Factor 3: Physical signs suggesting facet joint pain

- Factor 4: Physical signs suggesting discogenic pain

These factors correspond to how clinicians naturally differentiate competing LBP etiologies.

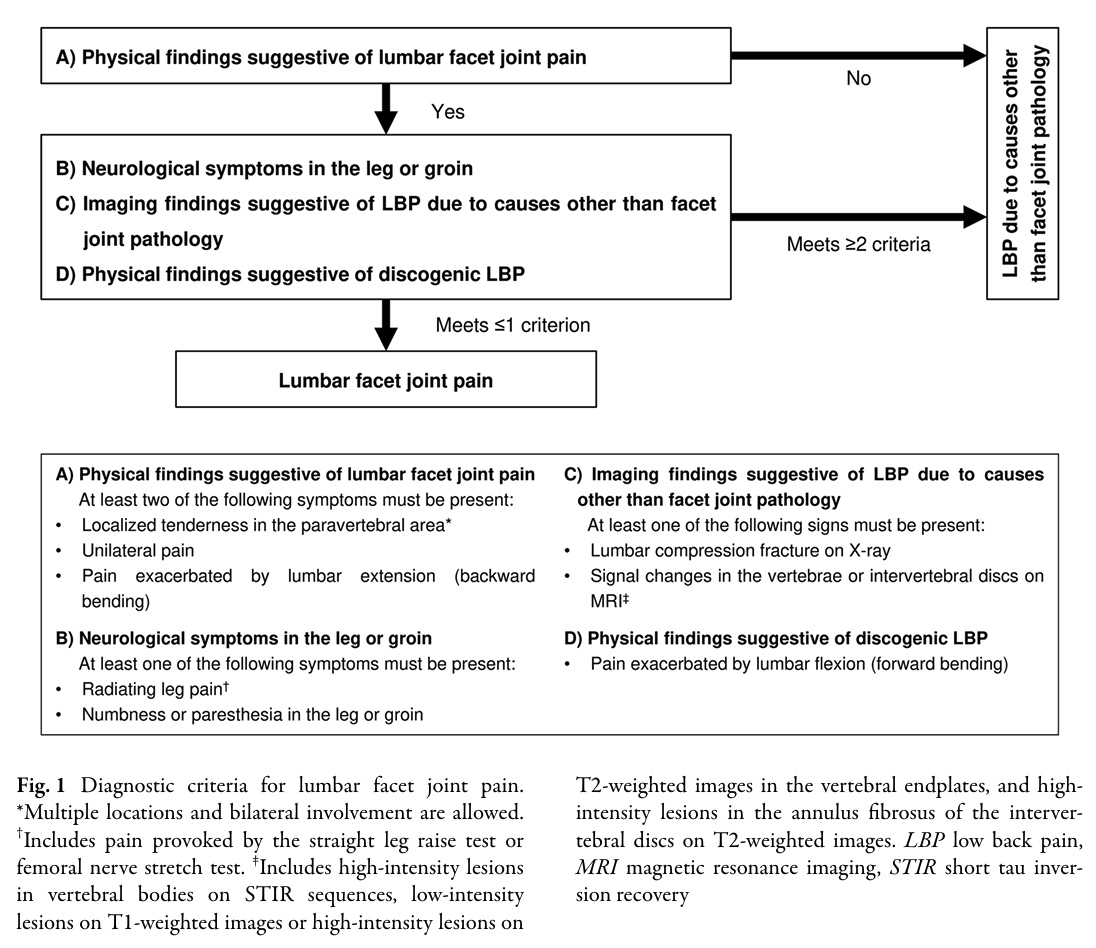

Step 3 comprised the development of the diagnostic criteria using a Delphi expert consensus. Using multiple consensus rounds (≥80% agreement threshold), items within each factor were combined into simple, practical diagnostic criteria (A–D). Finally, a decision rule was established, see below.

Results

Through all the Delphi rounds, 100% consensus was reached for recognizing lumbar facet joint pain using the following four criteria.

Facet joint pain is diagnosed when Criterion A is positive AND no more than one of Criteria B–D is present.

To diagnose lumbar facet joint pain, at least two of the following symptoms from Criterion A must be present:

- Localized tenderness in the paravertebral area (multiple locations and bilateral involvement are allowed)

- Unilateral pain

- Pain exacerbated by lumbar extension

The experts highlighted that, when at least two of these criteria are present, AND when no more than one of the following criteria (B-C or D) is positive, we can diagnose lumbar facet joint pain.

Criterion B: Neurological symptoms in the leg or groin. This criterion is positive when at least one of the following symptoms is present:

- Radiating leg pain, provoked by the Straight Leg Raise (SLR) Test or Femoral Nerve stretch test

- Numbness or paresthesia in the leg or groin

Criterion C: Imaging findings suggestive of low back pain due to causes other than facet joint pathology. This criterion is positive when at least one of the following signs is present:

- Lumbar compression fracture on X-ray

- Signal changes in the vertebrae or intervertebral discs on MRI

Criterion D: Physical findings suggestive of discogenic LBP

- Pain exacerbated by lumbar flexion

These criteria capture the core clinical pattern physiotherapists often observe:

- Extension-provoked, localized, unilateral pain

- Minimal neurological deficits

- Absence of strong competing discogenic or structural pathology signals

When more than one criterion B, C, or D is present next to a positive criterion A, the experts reached consensus that the low back pain is due to causes other than facet joint pathology.

Questions and thoughts

The authors noted that in older adults, multiple sources of low back pain often coexist, for example:

- Some facet joint irritation

- Some disc degeneration

- Some mild nerve irritation

- Some Modic changes

- Some arthritic changes

This means a purely “clean” clinical picture rarely exists. If the researchers made criteria that excluded anyone with ANY disc or neurological signs, then:

- Specificity (correctly ruling out non-facet pain) would go up

- But sensitivity (correctly identifying facet pain) would go down

- Many genuine facet-pain patients would be missed, simply because they also have some disc findings or some mild nerve symptoms

In real life, this happens very often. As the aim of this study was to develop a practical screening tool for primary care practitioners (including general practitioners, physiotherapists, and other non-spinal specialists) to spot patients who might have facet joint pain, the criteria had to be simple in use, not overly strict, but sensitive enough not to miss true facet pain in the coexistence of another mild finding. Therefore, the expert panel agrees that a small number of signs suggesting another source of pain is acceptable, as long as the key signs and symptoms indicating facet joint problems are present.

So they chose the rule:

Facet joint pain is diagnosed if Criterion A (facet signs) is present AND no more than ONE of B, C, or D is present.

Meaning:

- Criterion A = must-haves: (localized tenderness, unilateral pain, extension-provoked pain)

- Criteria B–D = “competing” signs: neurological signs, imaging pointing to other structures, flexion-provoked pain

The patient can have one competing finding, but not two or three. This makes the tool sensitive enough to catch more facet-pain patients, practical for real-world mixed presentations, and useful for guiding referral decisions.

The experts reached 100% agreement on this rule after two Delphi rounds. Think of it like a clinical probability system: If someone has the core facet cluster (unilateral, localized, extension-aggravated), AND they don’t have too many red flags pointing toward disc or nerve involvement, then facet joint pain remains a reasonable working hypothesis. But if they start accumulating several non-facet indicators, the likelihood shifts away from the facet origin.

Talk nerdy to me

These criteria help clinicians in recognizing lumbar facet joint pain and were supported by all of the orthopedic surgeons and spine specialists. Therefore, they have great value for clinicians who do not have access to specialized diagnostic equipment. But we must remain cautious, as these diagnostic criteria have not yet been validated, as indicated by the authors. That should be investigated in the near future to fully understand and implement these findings into practice. Yet, the Delphi study is a great starting point to improve our understanding, and to streamline our diagnostic processes to that of orthopedic spine specialists.

The transition from factor analysis to practical criteria required expert interpretation. This is where the modified Delphi method was essential: experts iteratively refined the number of factors, the naming of factors, and the practical decision rule until 100% consensus was reached. Delphi methods inherently incorporate expert bias, yet they remain standard in fields where no gold-standard data exist, or where the gold standard is too invasive.

While the study is pioneering in its attempt to operationalize facet joint diagnosis for primary care, its consensus-based nature comes with inherent drawbacks. Factor analysis organizes clinician perceptions of diagnostic items, but it does not confirm whether these clusters truly predict facet pain in patients. The criteria are logical, clinically coherent, and designed for feasibility, yet they await external validation against the gold standard: double diagnostic blocks. This means physiotherapists should interpret the criteria as promising but preliminary, suitable for guiding suspicion and referral rather than making definitive diagnoses.

Take-home messages

Abe et al. created simple diagnostic criteria designed to help primary-care clinicians and physiotherapists recognize when back pain may be coming from the facet joints, which is a treatable structure that is often missed. If a patient has 2 facet-like signs (localized tenderness, unilateral pain, extension-provoked pain) and not too many signs pointing toward nerve involvement or disc problems, facet joint pain becomes likely.

However, the biggest limitation is that these criteria have NOT yet been validated against the gold standard diagnostic blocks. If future validation shows poor accuracy, the entire decision rule may require revision. Until then, the criteria should guide clinical suspicion, not definitive diagnosis.

Reference

MASSIVELY IMPROVE YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LOW BACK PAIN FOR FREE

5 absolutely crucial lessons you won’t learn at university that will improve your care for patients with low back pain immediately without paying a single cent