Quadriceps impairments in preoperative ACL reconstruction rehab

Introduction

ACL injuries occur mostly in contact sports and lead to substantial absent time from sports. Whether or not someone opts for ACL reconstruction, physiotherapy plays an important role in preserving quadriceps function. In those opting for ACL reconstruction, preoperative physiotherapy was found to increase the return to sport rate and decrease the risk of reinjuries. Thus, it seems that preoperative quadriceps function is an important prognostic factor for good functional outcomes after ACL reconstruction. The timing for ACL reconstruction can, however, vary. Some get an early ACL reconstruction, others have surgery delayed by 6 months. There is up to now no consensus regarding preoperative quadriceps training protocols in ACL-injured knees and it is thought that the best timing would be to start preoperative ACL reconstruction rehab within 3 months. To understand at best what changes occur in the quadriceps muscle during this waiting period before reconstruction, this study was set up.

Methods

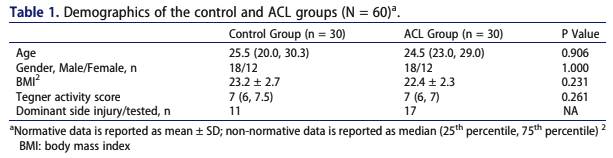

This cross-sectional study included 30 patients who were seen by an orthopedic surgeon with a complete ACL rupture within 3 months of their injury. They were between 18-40 years and usually physically active as reflected by their Tegner Activity Scale Score of more than 6 points. They were matched to 30 healthy controls.

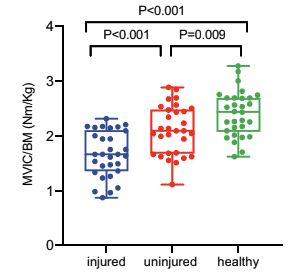

The primary outcome of interest was quadriceps strength and this was measured through the maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC). Three submaximal attempts were allowed before performing three maximal contractions of 5 seconds each. Both the injured and non-injured knees were tested and a rest period of 30 seconds was given in between the repetitions.

Results

The baseline characteristics revealed that both the injured participants and the healthy controls were comparable at baseline. The injured subjects were tested on average 35 (+/- 15) days from their ACL injury.

The measurement of quadriceps strength showed that in the participants with ACL injuries, the MVIC was lower on the injured leg than on the non-injured leg. When compared to the healthy controls, it was observed that also the non-injured leg had lower quadriceps strength compared to the controls.

Questions and thoughts

The observation of the lower quadriceps strength in the non-injured limb compared to controls may give a distorted picture. Sports participation is usually affected after an ACL tear and this may have led to the decreased quadriceps force compared to the healthy controls. Moreover, when an ACL injury occurs, arthrogenic muscular inhibition (AMI) is a typical deficit. AMI reduces muscular activation, which reduces muscle strength and results in abnormal movement biomechanics. Cross-over effects are also possible to result in a decrease in quadriceps strength.

In my opinion, the reduction of quadriceps force may also be due to fear, pain, or reluctance to load the muscle. I wouldn’t find it odd when someone with such an injury would rather avoid making it worse by really forcefully extending their knee. Further, we do not know to what extent the injured participants followed physiotherapy rehab, and as this variable was not controlled for, it could easily be that none of them participated in preoperative ACL reconstruction rehab. As such, it could be hypothesized that those participants demonstrate more quadriceps strength impairments.

Talk nerdy to me

Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot say confidently that the reduced bilateral quadriceps strength impairment is attributable to the ACL injury itself. It could be that the injured participants were already less strong compared to the healthy controls at baseline. Maybe, they had strength deficits that led to the current ACL injury. All variables we don’t know anything about and are thus not controlled for in this analysis.

This study made the recommendation to alter the limb symmetry index, as this value is used to express the strength difference between the healthy and injured limbs. As both values were lower than those of the quadriceps strength in the control group, the current LSI may be inaccurate and could overestimate the real strength differences between both legs.

Take home messages

Although this study design could not infer the exact causation, a reduction in quadriceps strength was observed in participants with an ACL injury compared to the healthy controls. In particular, the reduction of strength that also occurred in the non-injured limb has to be further examined. It would be necessary to include bilateral strengthening exercises to promote cross-over effects and minimize arthrogenic muscle inhibition.

Reference

Additional reference

LEARN TO OPTIMIZE REHAB & RTS DECISION MAKING AFTER ACL RECONSTRUCTION

Sign up for this FREE webinar and top leading expert in ACL rehab Bart Dingenen will show you exactly how you can do better in ACL rehab and return to sport decision making