Specific versus non-specific extensor muscles exercises in chronic neck pain

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that patients with neck pain often display altered muscle activation patterns and coordination issues between the contraction of the superficial and deep neck flexor muscles. These changes are now also seen in the cervical extensor muscles and subsequently, this may impact daily neck functioning. The training of the deep flexor muscles has shown beneficial effects in reducing pain and disability and increasing range of motion (ROM) and postural endurance. In this light, strengthening the deep neck extensors has been performed as it is thought to produce similar improvements. Studies have examined the execution of deep neck muscle strengthening and global exercises for the neck extensors. It is however unclear if training of the deep neck extensors is more effective compared to training of the extensor muscles in a more global way. The aim of this study therefore was to examine the effects of training of the lower deep neck extensors compared to global extension exercises on disability and pain.

Methods

To examine the effects of specific lower deep neck extensor training compared to general neck extensor exercises on pain and disability, a two-arm RCT was conducted. The trial included adult women reporting mild to moderate chronic idiopathic neck pain that was present for at least 3 months. Mild to moderate neck pain was defined as a VAS-scale pain intensity between 30 and 50/100. Every participant had poor performance (<250s) on a neck extensor resistance test.

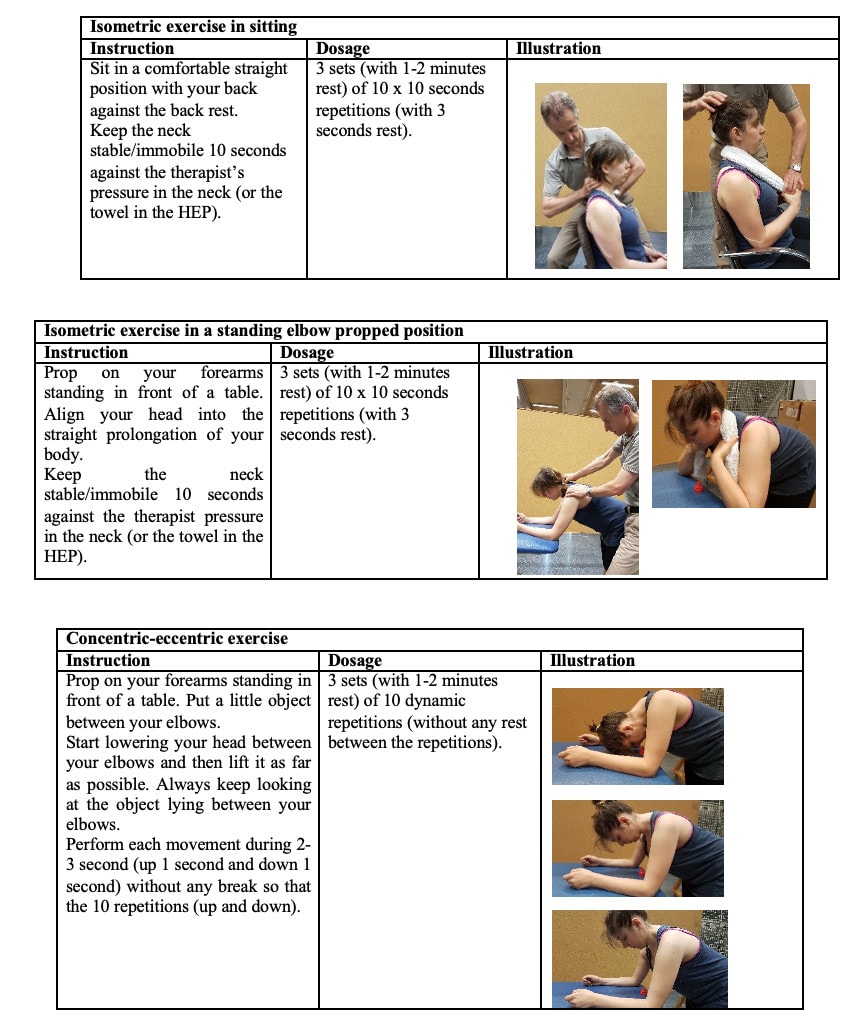

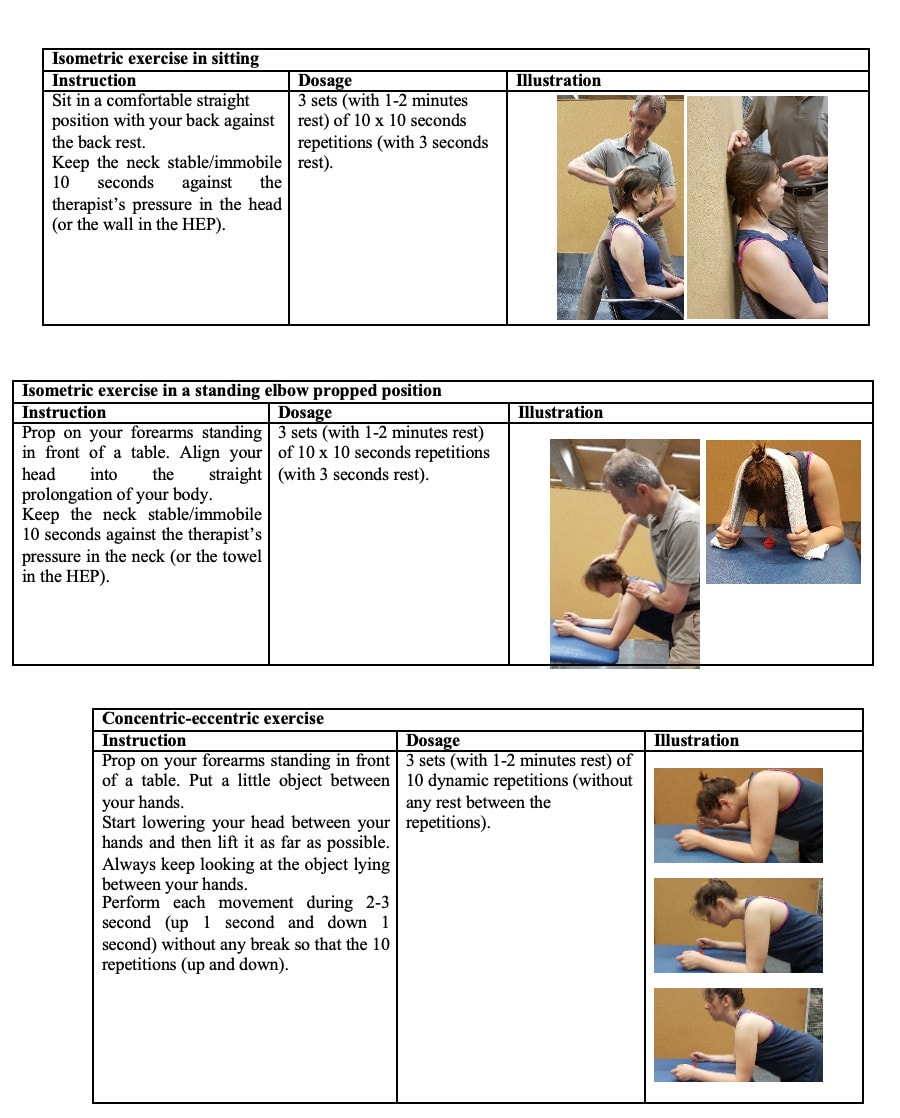

Patients enrolled in a 6-week exercise program were supervised once a week and performed home exercises twice a week. These sessions had an average duration of 20-25 minutes. In both groups, 2 isometric exercises and 1 concentric-eccentric exercise were performed. In one group the lower deep neck extensors training was performed with applied resistance to the vertebral arch of C4 and in the second group the general neck extensors were targeted by applying resistance to the occiput. The isometric exercises were performed in 3 sets of 6 repetitions of 6 seconds, with 6 seconds of rest between each repetition and a 1-2 minute break between sets. The concentric-eccentric exercise was repeated in 3 sets of 10 repetitions with 2-3 seconds in both the concentric and eccentric phases. Participants were asked to exercise at maximal pain-free efforts during all exercises.

Hereunder you can see the details from the lower deep neck extensors training with pressure applied to the vertebral arch of C4.

In the global neck extension program resistance was applied to the occiput.

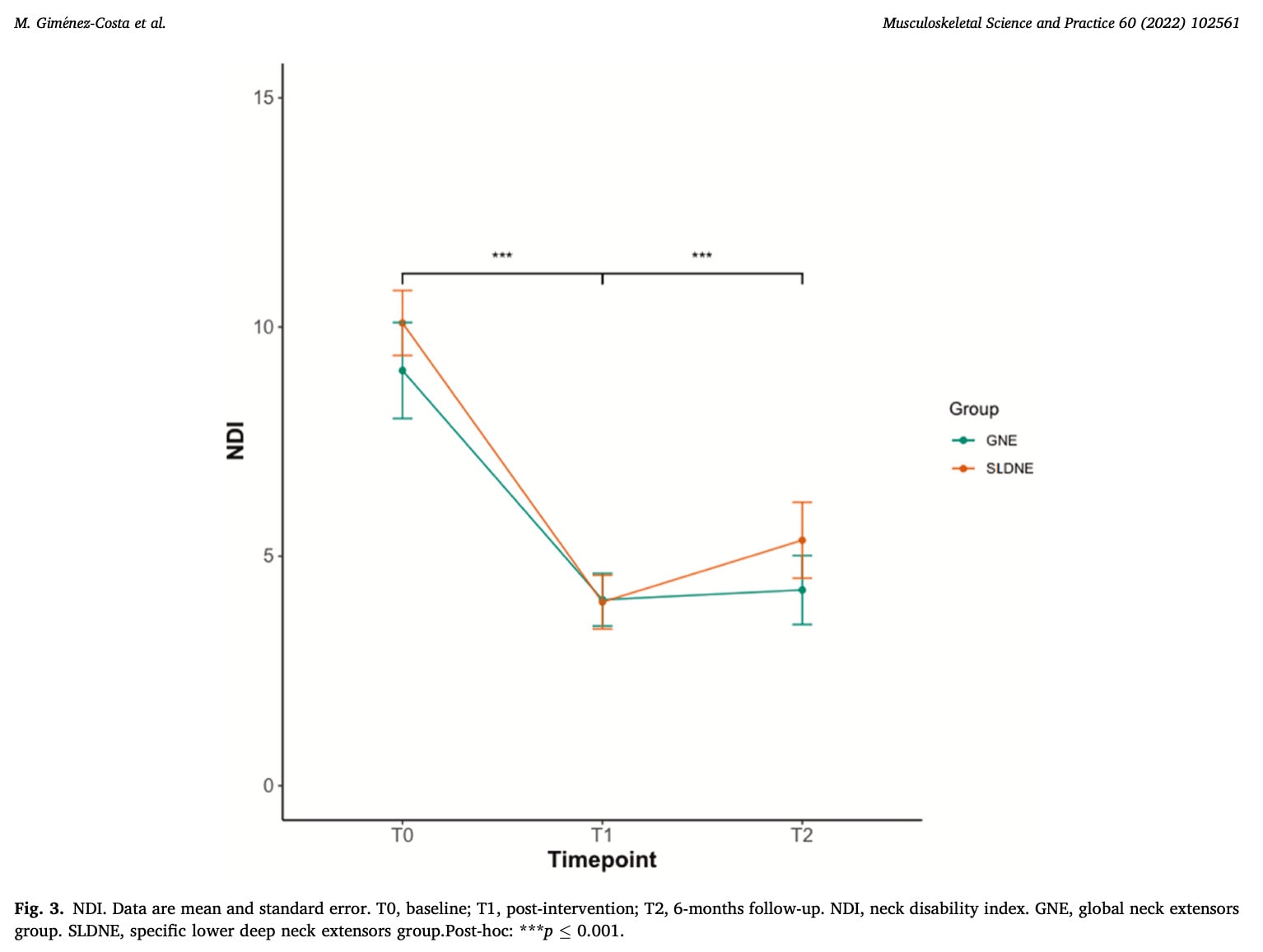

The primary outcome of interest was the Neck Disability Index (NDI) which ranges from 0-50 with higher scores indicating more neck disability. A change of 8.5 points had been previously determined to be clinically important. This was measured at baseline, immediately after the 6-week intervention, and 6 months later.

Results

Forty-six patients with neck pain were included in the trial and equally divided into the group performing the lower deep neck extensors training or the group performing the global neck extensor training. The analysis found a significant main effect for time. Compared to the baseline, both groups demonstrated improvement in the NDI. There was no significant between-group difference. The mean reduction in the group performing the lower deep neck extensors training was -6.09 (-7.75 to -4.42) immediately after the 6-week intervention. The mean difference in the general neck exercise group reached -4.73 (-6.57 to -2.91) at the same time point. After 6 months, this difference was still a statistically significant within-group difference in both groups: – 4.74 (-6.50 to -2.97) and -4.47 (-6.41 to -2.53) in the deep neck and global neck training groups, respectively.

Questions and thoughts

This review found no differences between a program designed to strengthen the lower deep cervical extensors and a program targeting the neck extensors more generally. However, in both groups, improvements were seen over the course of the study period and even after 6 months. These improvements did not exceed the minimal clinically important difference of 8.5 points and hence were not clinically relevant. The results give, however, a promising insight into the relevance of neck strengthening in people with chronic neck pain of a nonspecific origin. The fact that only 6 weeks were required to achieve these improvements, may be important to consider. What if the program had lasted for a week or two longer? Unfortunately, no true control group was included. These results could have been influenced by placebo/context effects. Therefore, a comparison of these two approaches with a do-nothing group would have been interesting.

In the last few years, much has been written about strengthening the deep cervical flexors. This study found improvements in both groups along the course of the study, but no important difference was seen when the deep extensors were compared to a general neck extensor program. Importantly, the differences in both groups did not surpass the minimal important difference. But given the short timespan and the reductions in disability observed, it may be a valuable tool for your rehab.

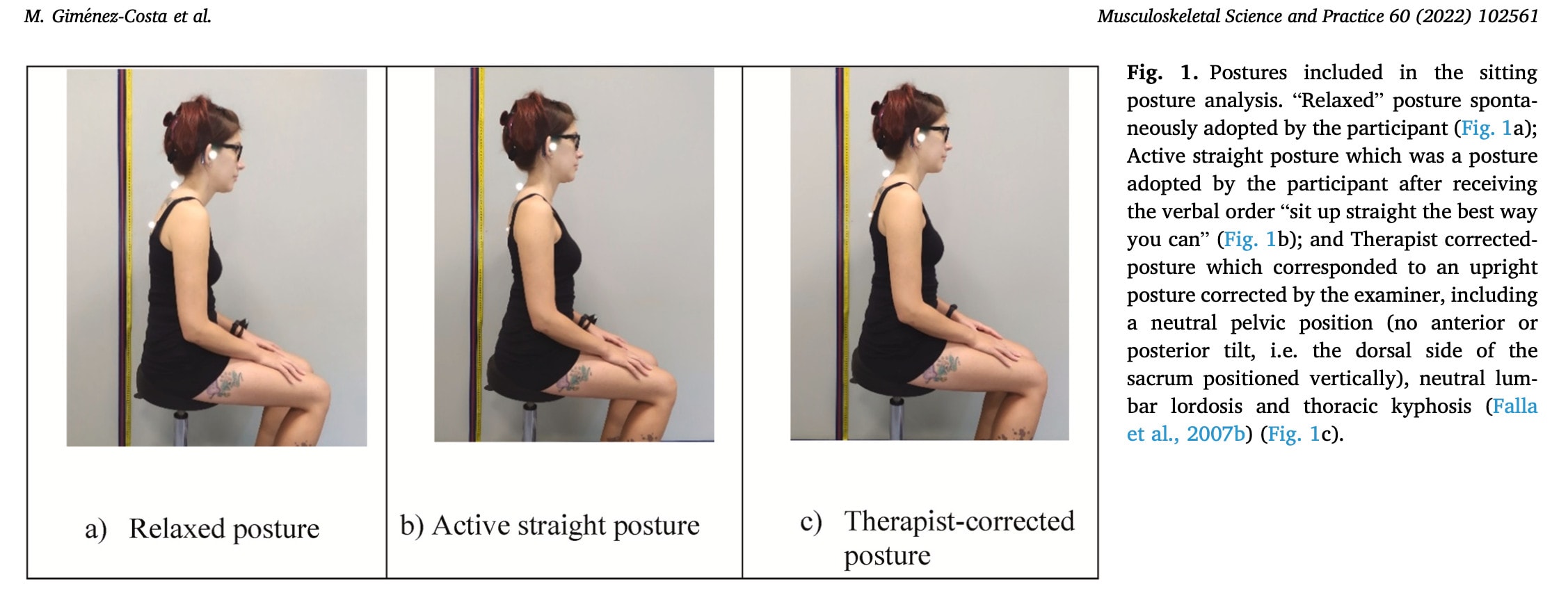

In my opinion, this gives you a wide array of possibilities to use in the rehabilitation of chronic neck pain. Maybe, someone with posture-related neck pain complaints will have more benefit from a combined intervention targeting the deep cervical flexors to adapt the protracted head posture and strengthening of the neck extensors to have a better sitting posture. I certainly don’t believe that there is a good and a bad posture, but rather there is room for improvement when it comes to sustained postures.

Talk nerdy to me

The authors refer to a poor performance on a neck extensor endurance test of less than 250s. The cited reference however doesn’t mention a performance test, so it remains unclear how a participant was examined to have a poor performance on the neck extensor resistance test. Therefore no recommendations can be made to use this in clinical practice, unfortunately. I see the relevance of this requirement for inclusion as people with weakness in the direction of neck extension will likely benefit from an intervention designed to strengthen the extensor muscles. Those with adequate endurance will likely show less improvement over a 6-week extensor strengthening program.

Looking at the secondary outcomes it becomes clear that the within-group improvements seen are extended in these outcomes as well. Significant improvements are seen in both groups in pain intensity, ROM, and local and remote hyperalgesia. Also in the relaxed position, a greater cervical angle was observed in both groups which points to a more upright positioning of the neck. The cervical angle was calculated using a line drawn from the tragus of the ear to the 7th cervical vertebra subtended to the horizontal. Importantly, the self-perceived benefit as measured using the Global Rating of Change (GROC) shows significant and clinically relevant improvements in both groups.

Take home messages

Lower deep neck extensor training is not more effective than a global neck strengthening program in women with chronic neck pain. Both approaches are effective in reducing neck disability measured on the NDI after 6 weeks and 6 months but these reductions are below the threshold for minimally important differences. However, the results may be promising as these were observed in a chronic neck pain population after only 6 weeks of minimalist intervention. One supervised session with 3 exercises and 2 home exercise sessions over 6 weeks was performed for 20-25 minutes each. Patients furthermore achieved improvements on every secondary outcome and had a clinically relevant self-perceived improvement after 6 weeks. This may therefore be achievable, relevant for your patient, and promising for future research!

Reference

100% FREE HEADACHE HOME EXERCISE PROGRAM

Download this FREE home exercise program for your patients suffering from headaches. Just print it out and hand it to them for them to perform these exercises at home