Pain with loading and stretching the Achilles tendon

Introduction

Pain is often rated on a scale from 0-10 or using questionnaires. But have you ever tried to summarize pain using a number? Not so easy, huh? This study wanted to look at pain during tendon loading and stretching tasks, so movement-evoked pain. This study aimed to characterize pain during varying intensity tasks of loading and stretching the Achilles tendon, relative to pain at rest.

Methods

This secondary analysis was performed from the study by Chimenti et al. (2023) to explore the effects of 2 different types of education plus exercise on pain and function in chronic Achilles tendinopathy. They concluded that adding a biopsychosocial-based education to exercise for Achilles tendinopathy did not improve pain and function compared to adding a biomedically-based education. We reviewed this article last week and from the results, we could conclude that it did not matter how you explained Achilles tendinopathy. Important to add is that the explanation in both groups was combined with a progressive exercise program. Check out our research review to learn more about it.

In this secondary analysis, the authors wanted to characterize the patterns of movement-evoked pain during tendon loading and stretching the Achilles tendon and to review the association between movement-evoked pain and the type of Achilles tendinopathy, biomechanical, and pain-related psychological variables.

Both people with midportion and insertional Achilles tendinopathy could be included when the Achilles tendon was the primary pain location. Symptoms had to be provoked by weight-bearing activities and rise to at least 3/10 when walking, doing heel raises, or hopping.

Participants were asked about their pain at rest (seated) and with 2 tendon loading exercises (walking fast and single-leg heel raise endurance test) and 2 tendon stretching exercises (standing with equal weight on both feet and standing calf stretching). Their pain was measured using the NRS immediately after they performed each task to quantify the level of movement-evoked pain.

Kinematic data were obtained during a minimum of 3 gait cycles and measured peak ankle dorsiflexion, peak knee extension, and peak hip extension at the end of the stance phase. Peak ankle power was calculated using inverse dynamics as the product of the net ankle moment and ankle angular velocity. Finally, the peak ankle dorsiflexion angle was assessed during a standing lunge with the knee bent and fully extended. Each position was held for 3–5 s.

To obtain the pain-related psychological variables, participants filled out the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-17) and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-13).

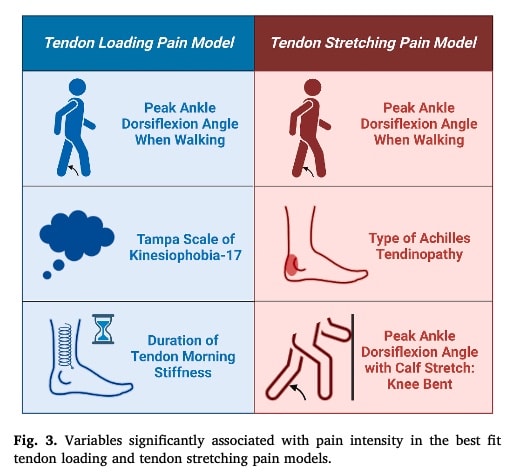

Two models were developed to characterize the extent of movement-evoked pain during activities loading and stretching the Achilles tendon.

Results

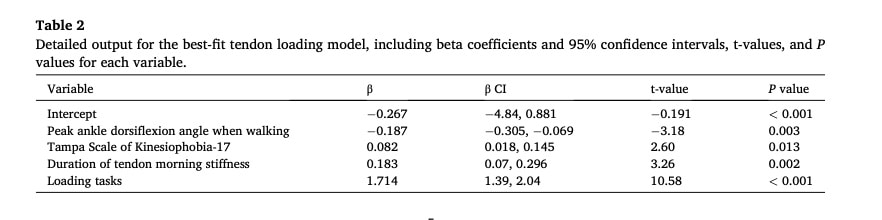

For pain resulting from loading the Achilles tendon, relative to rest, the model demonstrated the best fit when it included the peak ankle dorsiflexion during walking, TSK-17 score, and duration of tendon morning stiffness, in addition to the term for task (rest, walking, heel raises). This model explained 47% of the variance in pain intensity throughout the 3 tasks. There was no difference for subjects with insertional or midportion Achilles tendinopathy.

Peak ankle power was not associated with the loading tasks, while peak angle dorsiflexion was. It showed the highest association with changes in pain intensity across the tasks performed.

- 10° lower peak ankle dorsiflexion angle was associated with a 1.9-point greater pain intensity across loading tasks.

- A 12-point higher score in the TSK-17 or a duration of 50 min of tendon morning stiffness was associated with a 1-point increase in pain intensity.

Considering the model for tendon stretching, it found that the variables peak ankle dorsiflexion angle during walking and peak calf stretch angle were included in predicting pain intensity. Here, the authors found a difference of nearly 1 point increased pain intensity in the people with insertional Achilles tendinopathy with these tasks. This model explained 53% of the variance in pain intensity across the three stretching tasks.

- The model predicted a 0.8-point increase in pain intensity while standing from resting pain level as well as a 2.8-point increase in pain intensity with calf stretch from resting pain level.

- Peak ankle dorsiflexion angle during walking demonstrated the strongest association with pain intensity across tasks, suggesting that a 10° less peak ankle dorsiflexion angle was associated with 2.7 points greater tendon stretching pain.

- Also, a 10° greater ankle dorsiflexion stretch ROM was associated with a 1-point higher pain intensity across tasks. Insertional AT was associated with a nearly 1-point higher pain throughout tasks than midportion AT.

Questions and thoughts

What does this study show us? It shows us that pain increases with increasing intensity movements. Of course, fast walking and doing heel raises are more demanding than resting. This is not new. The tendon loading tasks were more painful with lower peak dorsiflexion and with higher kinesiophobia or 50 minutes of morning stiffness.

This could mean that it may be important to inform people with Achilles tendinopathy that when they fear an activity, it may become more painful. When they experience morning stiffness, you could tell them to be gentle when increasing their load on the Achilles tendon throughout the day. Maybe a gentle warm-up before rising could impact their morning stiffness and lead to a decrease in pain. Trying to improve the dorsiflexion seems reasonable, but maybe not using stretching, since this also increases pain. Eccentric exercises may seem best suited.

Considering the tendon stretching tasks, pain intensity rose by approximately 1 point with walking and nearly 3 points when doing a calf stretch. Also here, nothing new. What was special here was that lower dorsiflexion angle during walking led to almost an increase of 3 points of pain while more dorsiflexion range of motion during stretching also increased pain, by an average of 1 point. It seems that using more of the functional dorsiflexion range during walking may be beneficial. On the contrary, trying to improve dorsiflexion with stretching does not seem very effective.

Talk nerdy to me

This study examined associations between variables and the intensity of movement-evoked pain. It doesn’t say anything about what factors are causing the differences in pain experienced. Anticipation of pain, just to name an example, may also have had a spell on the intensity of pain felt during a task. In the current study, fear of movement was more associated with dynamic tasks than it was with static ones, so the perceived “threat” of a movement may be involved in the pain experience.

Greater use of mid-range ankle dorsiflexion during walking was associated with less severe movement-evoked pain with both tendon loading and stretching tasks, indicating that limited functional use of ankle dorsiflexion angle is associated with more severe pain. As such, trying to normalize gait may have an impact on pain intensity. It doesn’t necessarily mean that decreased levels of dorsiflexion are a driver of pain. Maybe muscle guarding that limits the range of motion as a response to anticipation of pain is causing the pain to increase.

Achilles tendinopathy is a condition in which pain typically increases with increasing demands, as was shown in this study. Contrastingly, in a study we reviewed a while ago, Sancho et al. (2023) found that pain was not correlated with increasing loads. The conclusion we could draw from this study was that on a group level, pain was not a proxy for loading tasks, and thus, loads could be increased early in the rehabilitation while increasing levels of pain should not be feared.

Take home messages

This study found associations between tendon loading and stretching the Achilles tendon and movement-evoked pain. The pain increased with increasing demands, but biomechanical variables and psychological variables were also incorporated into the increasing levels of pain. It appears thus that interventions should aim to target other components than just easing pain. Fear of movement was associated with pain felt during loading of the Achilles tendon.

Reference

HOW NUTRITION CAN BE A CRUCIAL FACTOR FOR CENTRAL SENSITISATION - VIDEO LECTURE

Watch this FREE video lecture on Nutrition & Central Sensitisation by Europe’s #1 chronic pain researcher Jo Nijs. Which food patients should avoid will probably surprise you!