Adductor Strength and Groin Pain

Introduction

Groin pain is a prevalent condition among football players and may lead to time loss. Early detection of groin pain has been proposed as an effective preventative measure. Reports indicate that groin pain may be associated with adductor weakness. But as we do not know whether the pain precedes adductor weakness or whether it is the other way around, this study sought to find out the interaction between weakness in adductor strength and groin pain onset.

Methods

A prospective study with longitudinal design was set up to include football players from a Major League Soccer club from the ages of under 13 years to under 19 years. Every week for 14 weeks, they were asked to report whether or not they experienced groin pain. If they did, the Numeric Pain Rating Scale from 0-10 was obtained.

Weekly, a long-lever adductor squeeze strength test was conducted using ForceFrame. Resistance was applied at 5 cm proximal to the medial malleoli. A 5-second maximal squeeze was performed, and one repetition was done each week.

Players were stratified into a groin pain and no groin pain groups based on their symptom reporting.

Results

The results were obtained from 53 players with a mean age of 14.4 years. Twenty-nine of them reported groin pain, while 24 did not experience groin pain in the 14-week study period. At baseline, there was no difference in demographics between the two groups. Equally, there was no difference in baseline adductor squeeze strength between those with and without groin pain.

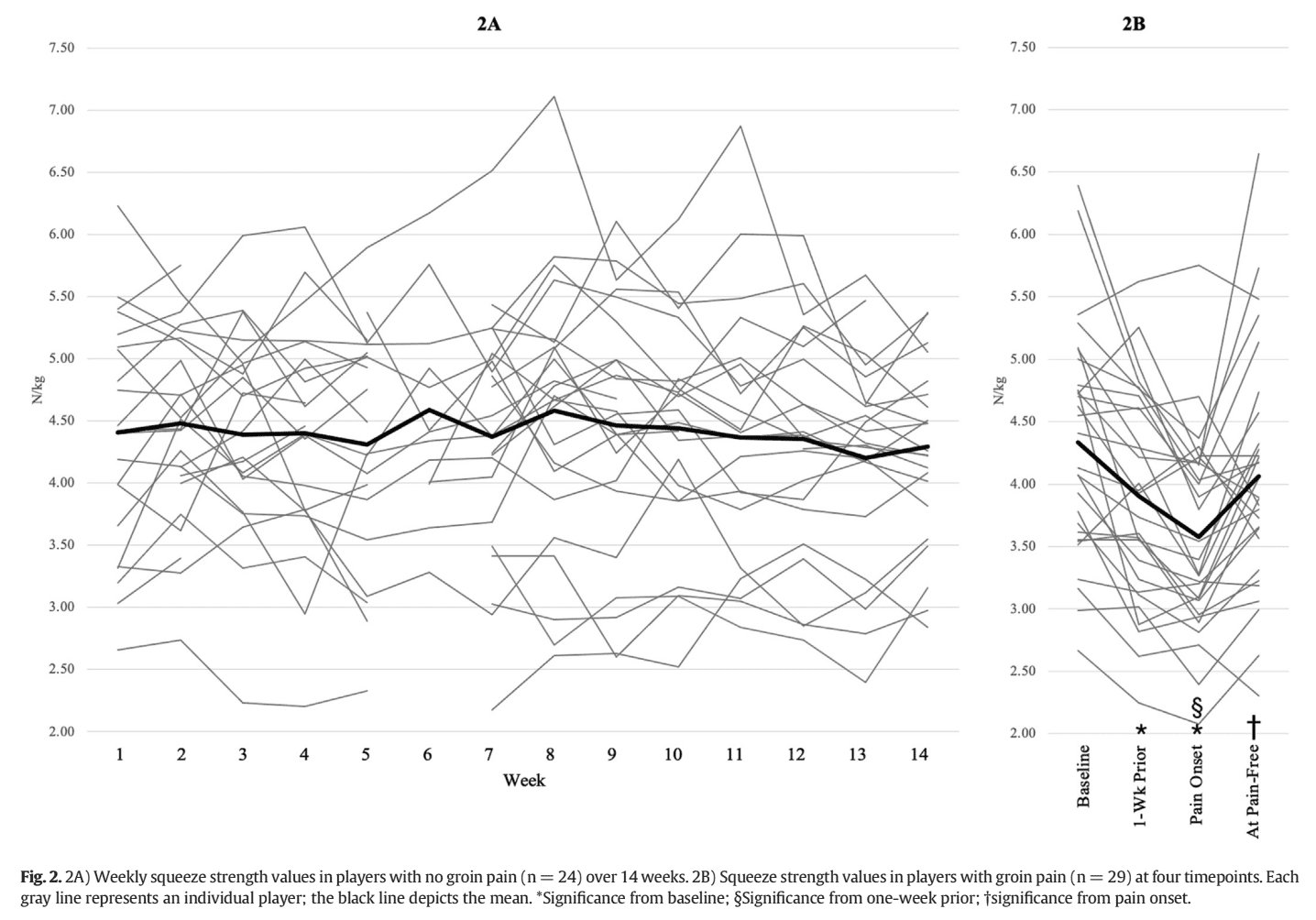

Those who experienced groin pain reported a mean severity of 3.1 (+/- 1.5) on the NPRS. The average duration of these symptoms was 2.1 weeks (+/- 1.3 weeks). The results revealed that those who reported groin pain had different adductor squeeze strength values across four timepoints, see Figure 2B.

Adductor strength decreased from baseline to the week before pain onsetIt continued to decline at pain onsetStrength increased at return to pain-free timepoint

What was especially interesting is that the players without groin pain had no differences in squeeze strength in the 14-week period.

Questions and thoughts

Is groin pain the reason for reduced adductor strength, or is a reduction in strength predisposing someone to the onset of groin pain? It’s like answering the question of the chicken or the egg. This finding of reduced adductor strength and groin pain onset was in accordance with an earlier small study by Crow in 2009 and Thorborg in 2014. It is proposed that a neuromuscular inhibition of the motor unit is seen before the conscious onset of pain. But we also know that pain can inhibit muscle function.

The report of pain was based on the following question: “In the last week, have you had any

hip or groin pain that has limited your performance in any way, on a scale of 0 to 10?”. This question could have been subject to interpretation, as some may have quit their performance upon the onset of pain, while others may have continued to perform and may have interpreted this otherwise.

Although this should be further tested, it is interesting to note that the players without groin pain had stable squeeze strength values over the 14 weeks. Similarly, those without pain did not differ at baseline from those who later developed groin pain. And more importantly, when the groin pain subsided, the strength values returned to the baseline value. Therefore, it seems reasonable to include this quick-screen test in football.

Talk nerdy to me

Overall force output was normalized by the BMI and expressed in Newtons per kilogram. This way, strength values could be compared between the individuals. In terms of consistency, it was ensured that the testing procedures were conducted at least 3 days following the last game played, in the middle of the week.

A limitation of this study may lie in the fact that only one maximal repetition of the adductor squeeze was performed. This is thus feasible in real-life situations. However, in research, mostly at least one test repetition or a minimum of three repetitions is allowed. This may have introduced hesitancy, especially in those already experiencing some groin issues or pain.

The long lever adductor strength was measured, as this had been shown to produce higher adductor torques with good reliability. Further, the long lever squeeze test has been found to be a risk factor for groin pain.

A cut-off value of 15% reduced strength was considered relevant in this sample. From those with groin pain (29 pain onsets), 16 onsets are characterized by a drop in strength of at least 15%.

This study did not take into account other variables such as (accumulation of) fatigue, training volume, and training data. Thus, further research is needed to control for these factors.

Take home messages

The relationship between adductor strength and groin pain found here does not imply a causational relationship. The fact that the same relationship was found in other studies, could mean that a reduction in hip adductor strength could predispose someone to groin pain. Preventative measures can be easily implemented when these reductions are found upon screening.

Reference

LEVEL UP YOUR DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IN RUNNING RELATED HIP PAIN - FOR FREE!

Don’t run the risk of missing out on potential red flags or ending up treating runners based on a wrong diagnosis! This webinar will prevent you to commit the same mistakes many therapists fall victim to!