Early or Delayed Physiotherapy for Active Lumbar Spondylolysis in Adolescents

Introduction

Pain in the lumbar area in young individuals is uncommon and should be identified accordingly. Active lumbar spondylolysis is a condition in which a stress fracture occurs in the pars interarticularis in one of the lumbar spine vertebrae, and it is classified as a form of specific low back pain. It is a condition that merely affects the young and active adolescent population. Rest and activity cessations have been typically prescribed in the past. Due to the negative consequences of detraining and activity avoidance, more efforts have been put into studying alternative ways of helping youngsters affected by this condition. In 2021, we made a video about a single-arm prospective study by Selhorst et al., which studied the feasibility and safety of an immediate functional progression program for active lumbar spondylolysis in adolescents. Back then, the evidence was still preliminary but promising and calling for a full-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT). Now that full-scale RCT is available, we will break it down step by step in this research review.

Methods

This study included adolescent participants between the ages of 10 and 19 years who had an MRI-verified active lumbar spondylolysis, defined as observable edema in the posterior elements of the lumbar vertebrae at the pars interarticularis, with or without a fracture. They had to be engaging in organized sports at least twice per week at the time of diagnosis or onset of their low back pain. All participants were recruited from the sports medicine departments of two pediatric hospitals in the USA. Exclusion criteria were rest from activity for more than 4 weeks due to low back pain, numbness or tingling in any lumbar dermatome, previous lumbar spine surgery, or a prior injury or condition that would make the physiotherapy plan inappropriate (for example, a co-existing knee injury).

Eligible candidates were randomized into one of two groups: the “early physiotherapy” or the “rest before physiotherapy” groups.

None of the participants received a brace. All participants had to take a break from all sports activities at the time of their study participation. Every participant, regardless of group assignment, received two personalized 1-hour physiotherapy sessions per week until they met the return to sport criteria.

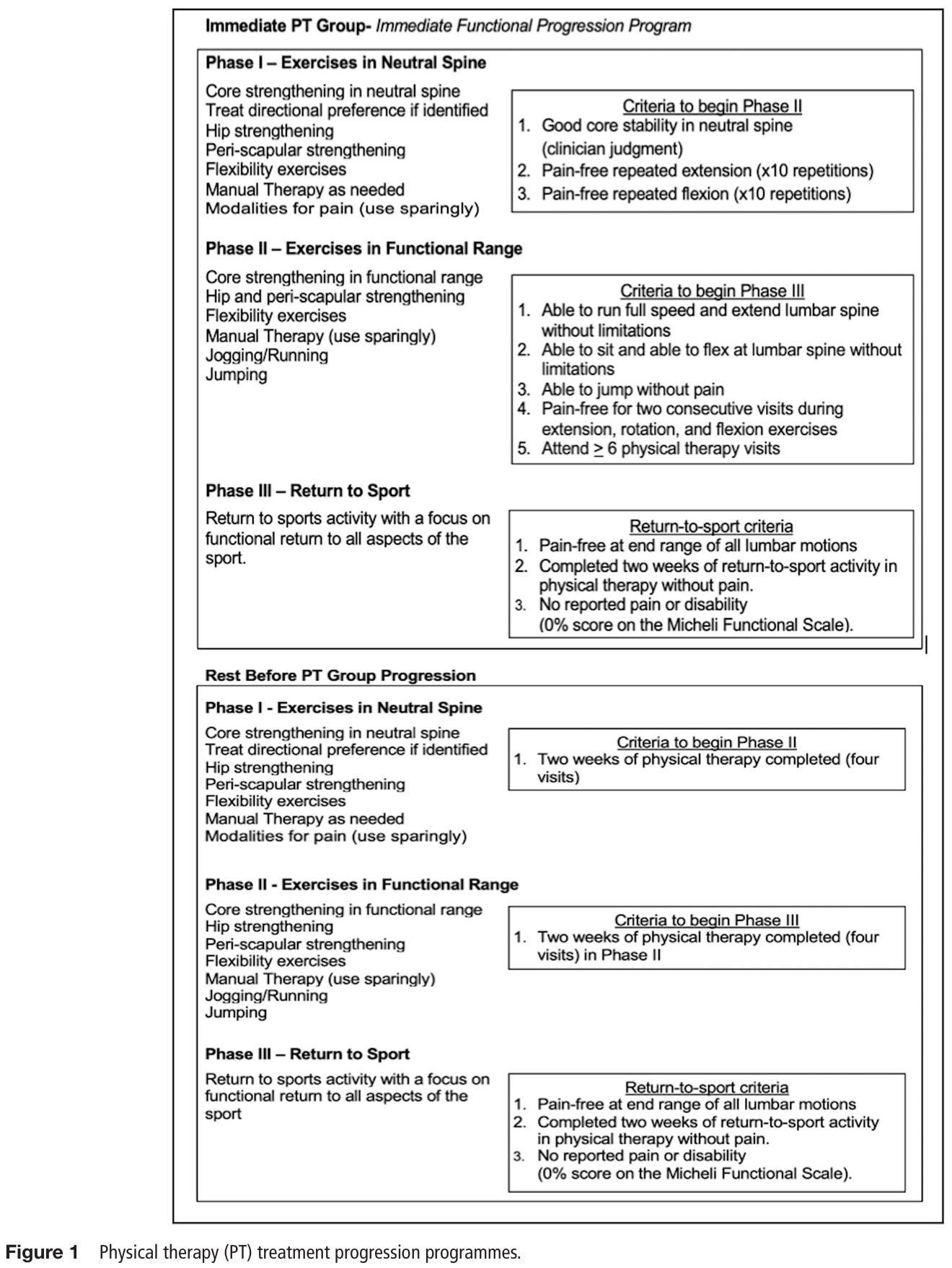

Immediate physiotherapy

Adolescents with active lumbar spondylolysis who were randomly assigned to the immediate physiotherapy group started the rehabilitation within seven days of their diagnosis. This program followed a structured approach with progressions based on set criteria for function and pain.

Rest before physiotherapy

The participants in this group rested until their low back pain resolved for at least two consecutive days, and when this was the case, they initiated physiotherapy within seven days of pain resolution. They followed the same physiotherapy program, except for the progression criteria. In this group, progressions were made in a time-based manner, since their pain had resided before they could start the physiotherapy.

Return to sport criteria

Athletes, irrespective of the group they were randomized to, were cleared to return to sport and discharged from care after completing their PT protocol and meeting all three of the following criteria:

- Pain-free repetitive motion to end-range in all cardinal lumbar directions.

- Completion of two weeks of return-to-sport activity in PT without pain.

- No reported pain or disability (0% score on the Micheli Functional Scale (MFS))

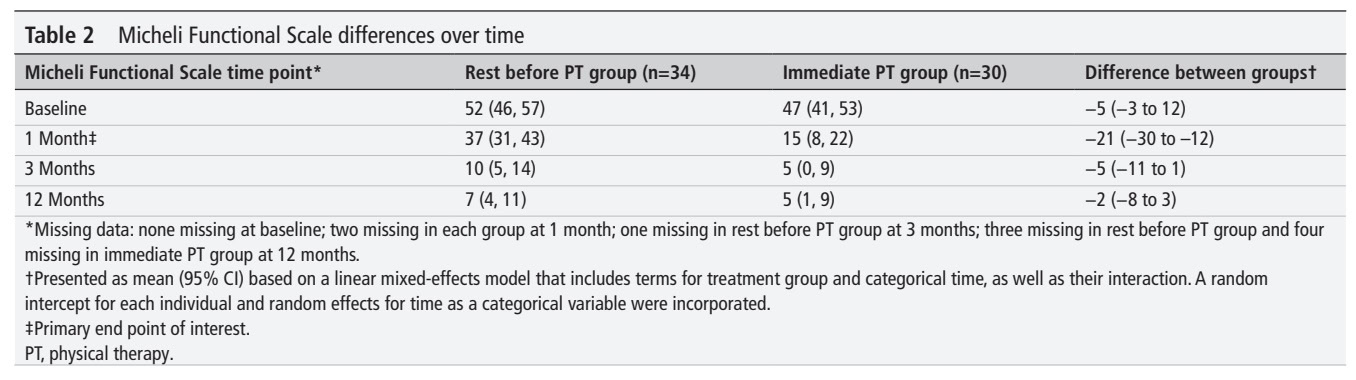

The primary outcome was the Micheli Functional Scale (MFS), which is a 0-100 questionnaire that assesses pain and function in adolescents. The authors set the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) at 20 points, but had no reference.

Secondary outcomes included:

- Time to return to sport

- Recurrence rate of low back pain in the following year, defined as seeking medical treatment.

- Healing on MRI at 3 months.

- Patient-reported outcome on depressive symptoms, fear of movement, and quality of life

- Atrophy of the lumbar multifidus muscles, measured by measuring the cross-sectional area at L4-L5.

Results

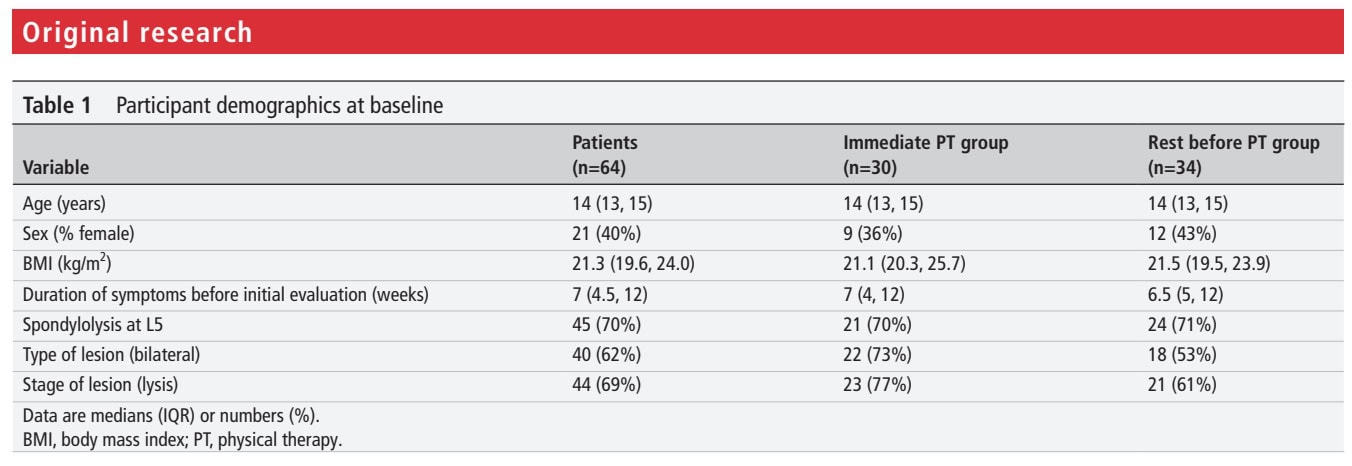

The study included 64 adolescents suffering from low back pain due to active lumbar spondylolysis. Thirty were randomized to the immediate physiotherapy group and 34 to the “rest before physiotherapy” group. The groups were well-balanced at baseline, with comparable characteristics across groups.

At baseline, there was no significant difference between the groups in the primary outcome measure. Those in the immediate group started physiotherapy at a median of 6 days (Interquartile range (IQR): 4-7 days). The “rest before physiotherapy” group started only once their symptoms subsided, and this was at a median of 28 days (IQR: 21-39 days).

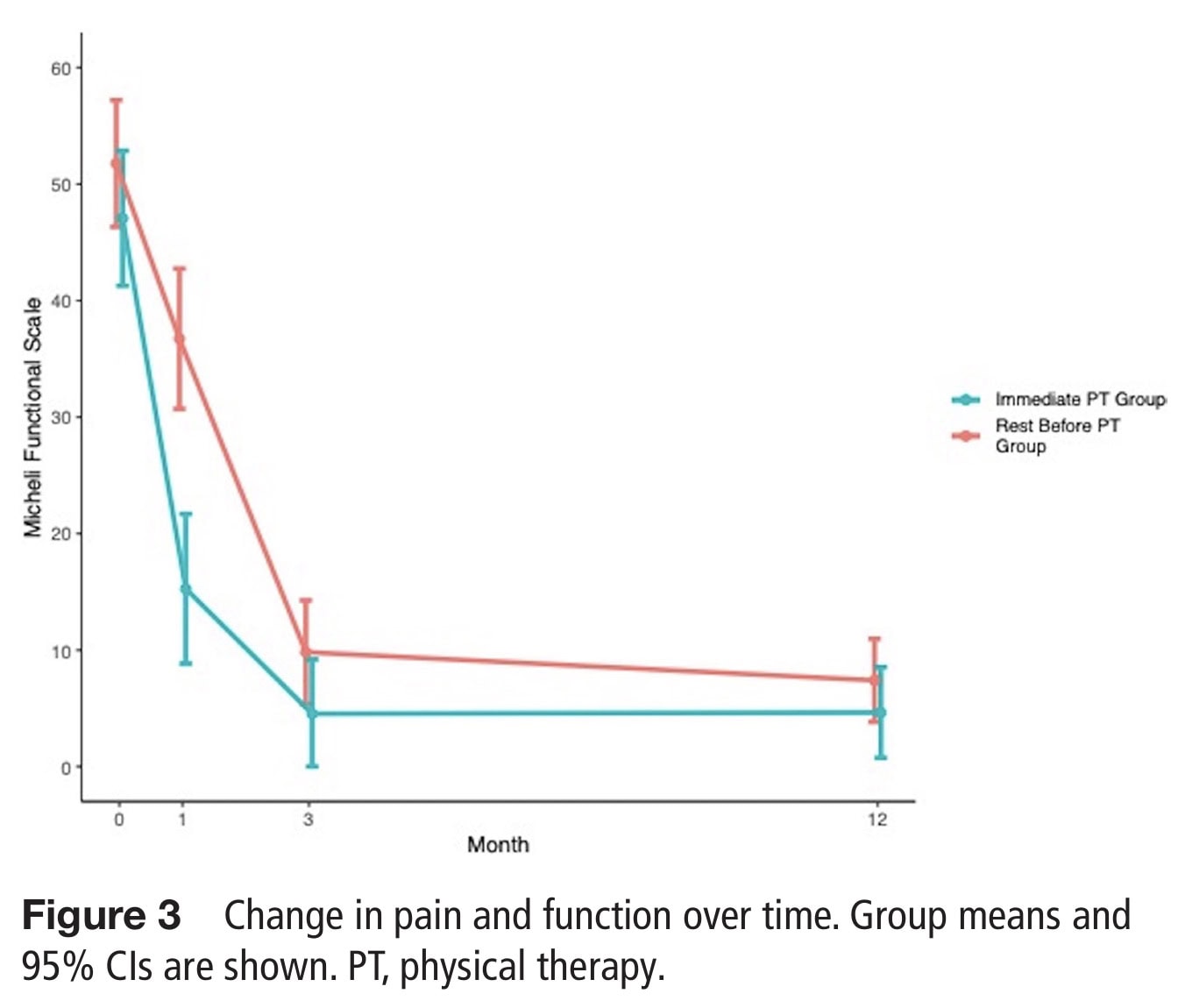

By one month, the participants in the immediate physiotherapy group had improved by 32 points, compared to 15 points in the “rest before” group. This produced a significant between-group difference of -21 points, favoring the immediate physiotherapy group. The 95% confidence interval ranged from -30 to -12 points.

By the third month, the participants in the immediate group and the “rest before physiotherapy” group achieved similar outcomes on the primary outcome. The between-group difference was -5 (95% CI:-11 to 1) in favor of the immediate group, but this difference was not statistically significant. The same was observed for the primary outcome at 12 months.

Questions and thoughts

The current study showed that starting early with physiotherapy in the case of active lumbar spondylolysis in adolescents should not be feared. The secondary outcomes supported the findings of the primary analysis:

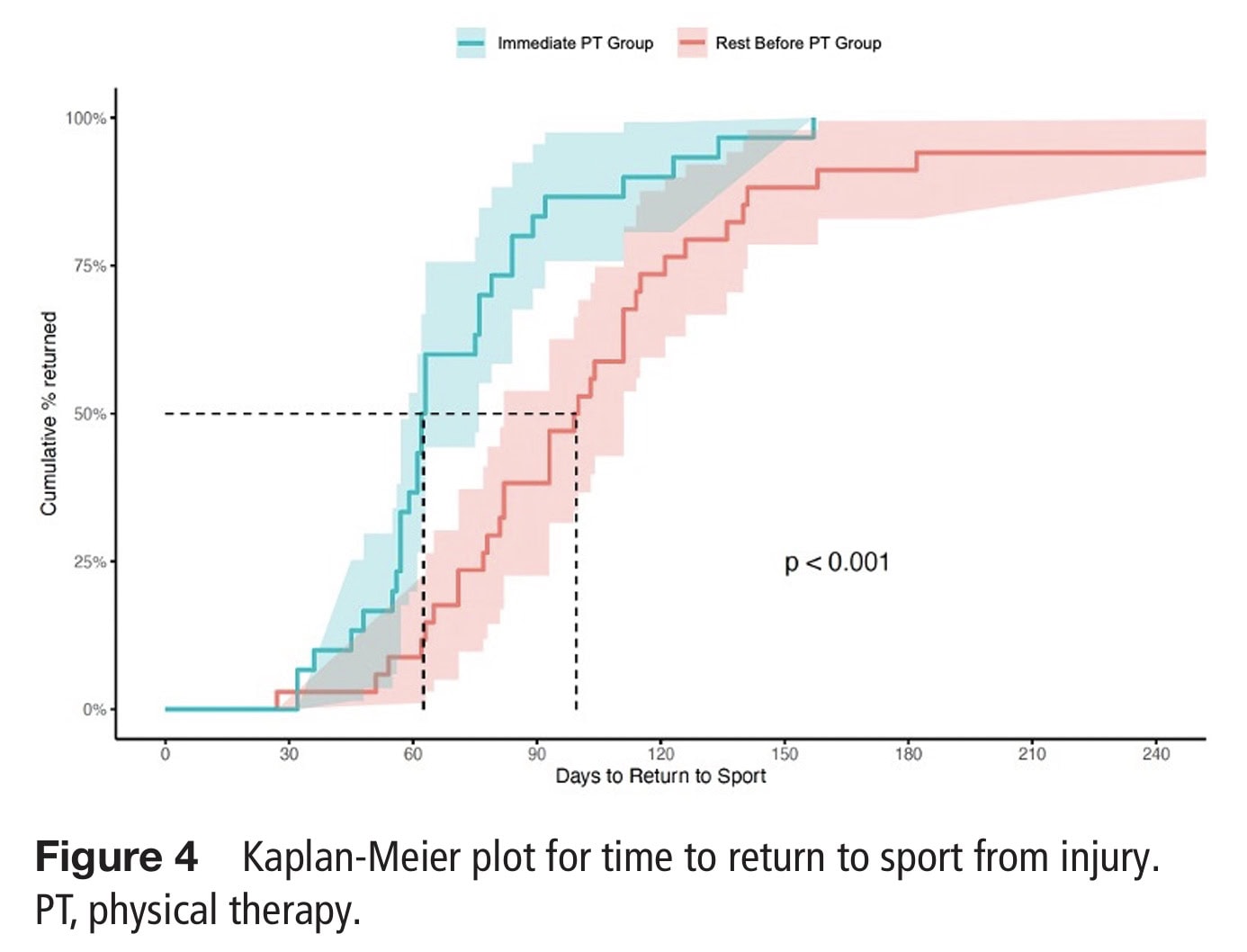

- Time to return to sport outcomes revealed that the participants in the immediate physiotherapy group returned 38 days sooner than those in the “rest before” group. The participants in the immediate group returned at a median of 74 days, compared with a median of 112 days in the “rest before” group. The Kaplan-Meier plot shows the difference in favor of the immediate physiotherapy group.

- The recurrence rate of low back pain in the following year was in favor of the immediate group, which experienced fewer recurrences. One participant (3%) from this group sought further medical care for low back pain, compared to 10 adolescents (29%) in the “rest before physiotherapy” group.

- Healing was examined in 53 of the 64 included adolescents who obtained their MRI at three months. In 41 (77%) of the 53 participants, significant healing was observed. In the immediate physiotherapy group, 84% achieved this significant healing, compared to 71% in the “rest before physiotherapy” group. There was no difference in bony healing on MRI.

- Atrophy of the lumbar multifidus muscle, measured by measuring the cross-sectional area at L4-L5, demonstrated that it increased by 7 percent (1.5 cm2) in the immediate physiotherapy group, whereas it decreased by 1.4% (0.20 cm2) in the “rest before physiotherapy” group, leading to a between-group difference of 1.7 cm2 (95% CI: 0.2 to 3.2 cm2).

- Patient-reported outcomes on depressive symptoms, fear of movement, and quality of life revealed that there were no significant differences between groups across the study.

In 2022, we published another research review, evaluating a test battery for its diagnostic ability in identifying active lumbar spondylolysis.

Talk nerdy to me

The study used two outcomes for which no select MCID was provided. As a secondary outcome, the lack of an MCID for the cross-sectional area may not really limit the findings, but for the primary outcome, missing such a clinical interpretation of the important differences is more problematic. The authors proposed a 20-point difference on the 0-100 MFS, but provided no reference to support this.

Another limitation we came across when reviewing the study was the apparent subdivision the authors made between bony healing outcomes on MRI and significant healing. The paper literally states: “By 3 months, 41 (77%) of all imaged participants demonstrated significant healing on MRI (immediate PT=84%, rest before PT=71%), five (9%) demonstrated no change (immediate PT=8%, rest before PT=10%) and seven (13%) had worsened (immediate PT=8%, rest before PT=18%). Bony healing on MRI demonstrated no significant differences between groups (p=0.30).”

So why the subdivision between healing and bony healing?

The study’s text uses the terms “significant healing” and “bony healing on MRI” to describe the same overall outcome—the healing of the spondylolysis stress injury as viewed on the 3-month MRI—but with a slight difference in context:

- “Significant Healing”: This term is used to present the observed rates of improvement for each group. The radiologist, who was blinded to the group assignment, compared the 3-month MRI to the baseline MRI for changes in the lesion and the associated oedema. Based on this comparison, the lesions were classified as either healing, showing no change, or having worsened, which yielded the observed rates of “significant healing” for each group. The observed rates of significant healing were 84% for the immediate PT group and 71% for the rest before PT group.

- Bony Healing on MRI: This term refers to the statistical comparison of the healing outcome between the two groups. Although the observed rates of significant healing were different (84% vs. 71%), the statistical test showed that this difference was not significant (p=0.30).

- As such, using the wording “significant healing” is a misleading statement or at least a linguistic trap. In essence, there is no division in the underlying outcome being measured; the difference is in how the results are reported:

- The raw descriptive percentages are labeled as “significant healing”.

- The inferential statistical test comparing those percentages between the groups is labeled as “Bony healing on MRI” and was not significant.

- To be clear: both groups achieved a good healing rate within 3 months. Probably, if the MRI had been taken sooner, it could have revealed differences, but that is mere speculation.

Take-home messages

For MRI-identified active lumbar spondylolysis in adolescents, relative rest appears to be outdated. This RCT demonstrated that starting physiotherapy right away may speed up functional recovery and return to sport, and enhance the cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscles. At the same time, it did not impact the healing rates of the pars interarticularis stress fracture, given the good outcomes in both groups.

Reference

MASSIVELY IMPROVE YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LOW BACK PAIN FOR FREE

5 absolutely crucial lessons you won’t learn at university that will improve your care for patients with low back pain immediately without paying a single cent