Accelerated versus control rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction

Introduction

When working with ACL reconstructed patients you are probably familiar with the rehabilitation timeframes that should be followed. These different steps to take in the rehab are largely determined by the process and timeframe of tissue revascularization. However, even when those predetermined time frames are respected, problems of poor recovery of strength and muscular function arise and some individuals even re-tear their operated ACL. It is frequently reported that many patients receive inadequate rehabilitation with severe underloading and insufficient complexity built into the program. But as some procedures are often delayed, this may also have a spell on the less optimal recovery. This study sought to compare an accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol to enhance strength and functional symmetry after ACL reconstruction to a control program where progressions were delayed to existing timeframes. The primary outcome of interest was graft laxity to see whether the accelerated program is safe for the healing ACL.

Methods

In this randomized controlled trial 44 patients between 16 and 45 years who underwent surgical reconstruction of the torn ACL were included. “A remnant sparing, double-bundle technique was used using ipsilateral semitendinosus and gracilis hamstring tendons. The anteromedial bundle was reconstructed using doubled semitendinosus and the posterolateral bundle with doubled gracilis tendon.”

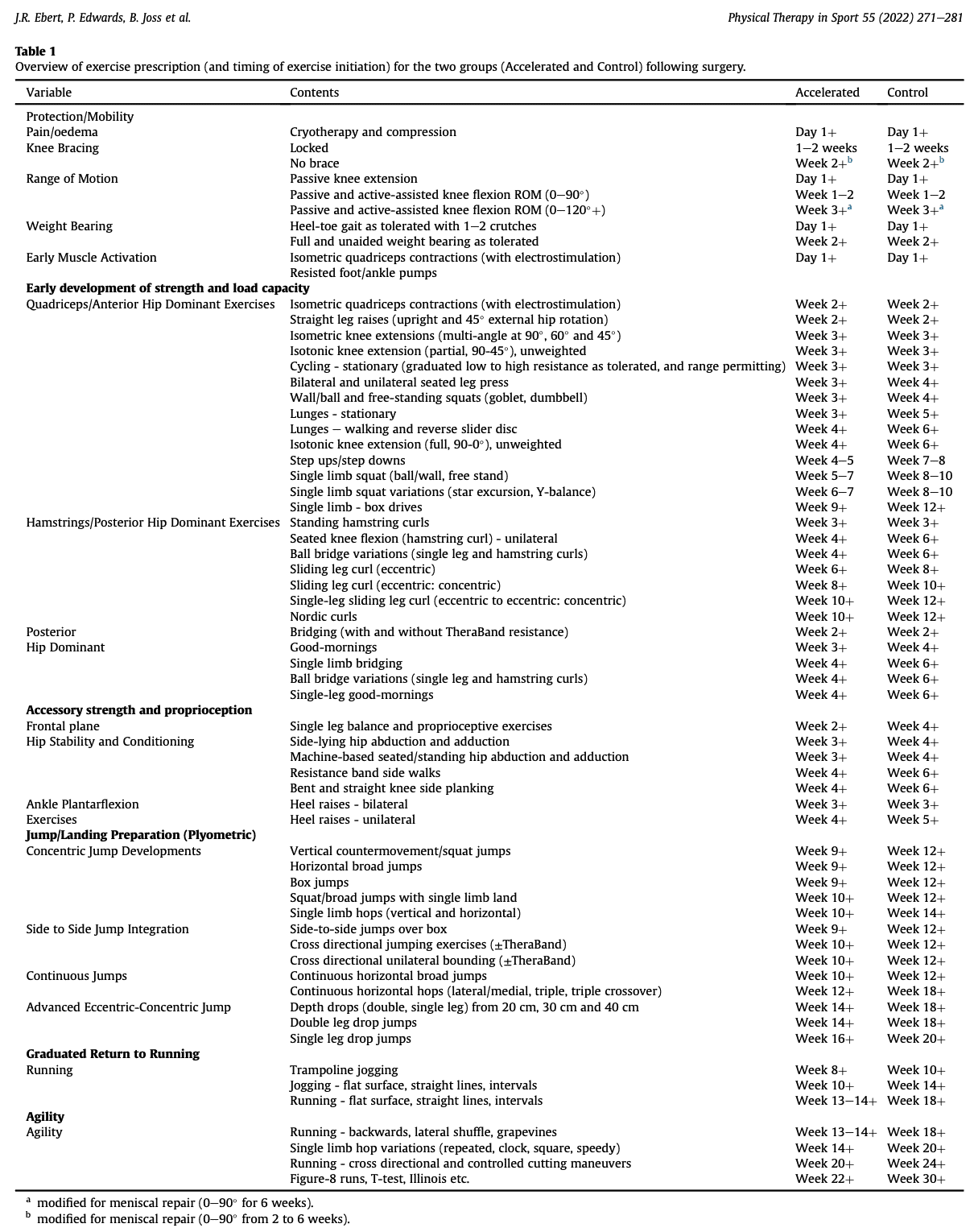

Rehabilitation was supervised and took place in a private outpatient clinic. The early phases were standardized and included weight-bearing as tolerated early circulatory and ROM exercises. Hereafter, the group following the accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol progressed quicker through the different stages than those in the control arm. A comparison of rehabilitation steps can be seen in the picture below.

The supervised sessions were supplemented with progressive and independent home/gym-based rehabilitation. The supervised component was held 3-4 times per week during the first 4 months, 2-3 times per week in months 4-6, and again 3-4 sessions per week between 6 and 12 months. The dosage was generally focused on muscular endurance (2-3 sets of 15-20 reps) initially, followed by strength (3-4 sets of 6-12 reps) and then power/stretch-shortening cycle exercises (5 sets of 8 reps). In each session, 8-15 exercises were performed.

The initiation of jumps and hopping exercises was determined by the proficiency in single-leg squats (through a range of 75°-90°), interval straight-line jogging was permitted when at least 15 single-leg calf raises and at least 10 single legs squats were possible (through 75°-90°) as well as proficiency in weight acceptance and sound mechanics during the jump and hopping activities was seen.

It was advised not to return to sport before 9 months post-surgery and a minimum of objective measurements had to be performed properly. Those included achieving a minimal limb symmetry index equal to or above 90% for the following:

- Full active knee extension and flexion

- Peak knee extensor and flexor strength

- Hop tests

- 1) the single hop for distance (SHD, m),

- 2) the 6 m timed hop (6MTH, s),

- 3) the triple hop for distance (THD, m)

- 4) the triple crossover hop for distance (TCHD, m)

At 6, 9, 12, and 24 months post-surgery the side-to-side graft laxity was measured via the anterior tibial translation test, using an arthrometer. This was the primary outcome variable of interest.

Results

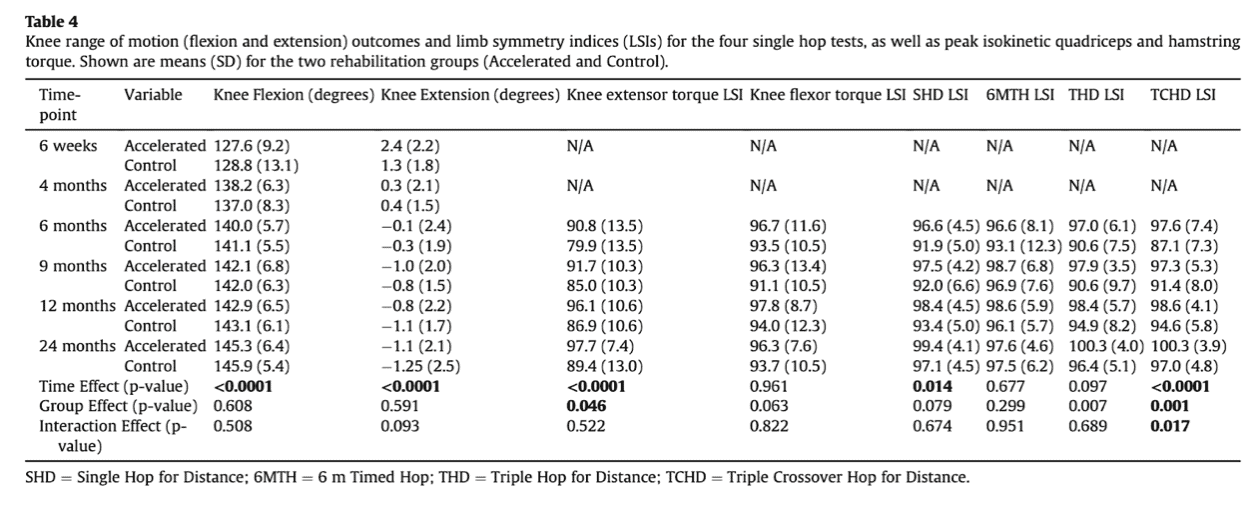

At baseline the groups were comparable. At 24 months there was no difference in side-to-side graft laxity between the accelerated and control group. Peak knee extensor strength LSI was higher in the accelerated group at 6, 12, and 24 months post-surgery.

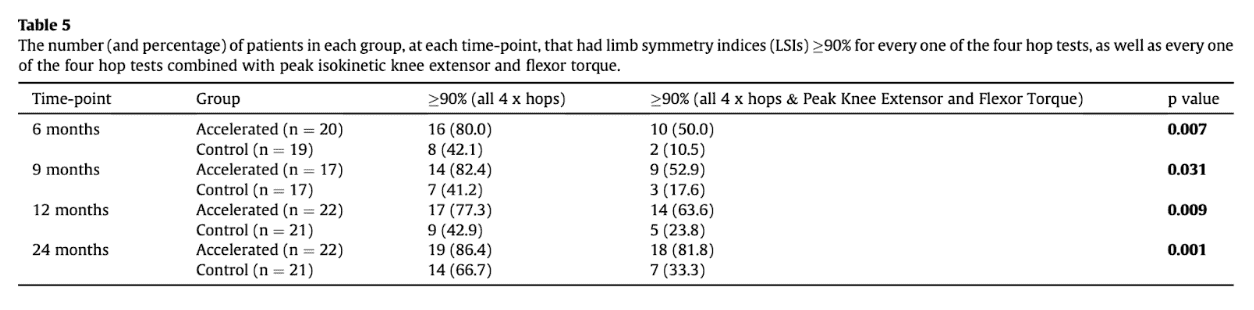

Post-hoc t-tests demonstrated a significantly higher LSI for the SHD in the people following the accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol at 6 and 9 months post-surgery, as well as a significantly higher LSI for the TCHD in the accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol at 6 and 9 months. A significantly greater percentage of accelerated patients demonstrated an LSI above 90% for all physical measures (all 4 hop tests and knee extensor and flexor strength). When combined in the form of a “test battery”, a significantly greater percentage of patients in the Accelerated (versus Control) group ‘passed’ the full series of physical tests at all time-points (for example, this was 50.0% versus 10.5% at 6 months, and 81.8% versus 33.3% at 24 months).

Overall, a significantly greater percentage of Accelerated (77.3%) versus Control (59.1%) patients were participating in Level 1 or 2 pivoting sports at 12 months post-surgery. At 24 months 86% of participants in both groups returned to their pivoting sport activities.

Questions and thoughts

More patients in the accelerated group were participating in level 1 or 2 pivoting sports and this difference was statistically significant but disappeared at 24 months. This would mean that at 24 months, the participants in the control group achieved the same functional milestones to allow participation in those kinds of sports as patients following the accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol. At 1 year, however, only 59% of control patients were participating in level 1 and 2 pivoting sports compared to 77% of the accelerated group. This was demonstrated by the ACL-RSI, a patient-reported outcome measure that has a practical online application, accessible through: https://orthotoolkit.com/acl-rsi/. Therefore, as the results revealed no difference in laxity following the accelerated program and a significant difference in knee extensor strength recovery and participation in pivoting sports, the safety of this program seems proven.

The authors found significantly higher limb symmetry indices for the single hop for distance (SHD) and triple crossover hop for distance (TCHD) in the accelerated group at 6 and 9 months. As the operated limb approaches the functional capacity of the non-affected leg, it sounds reasonable that this may have boosted confidence in one’s knee. This, together with the more rapid increases in knee extensor strength may have contributed to the increased readiness to participate in pivoting sports.

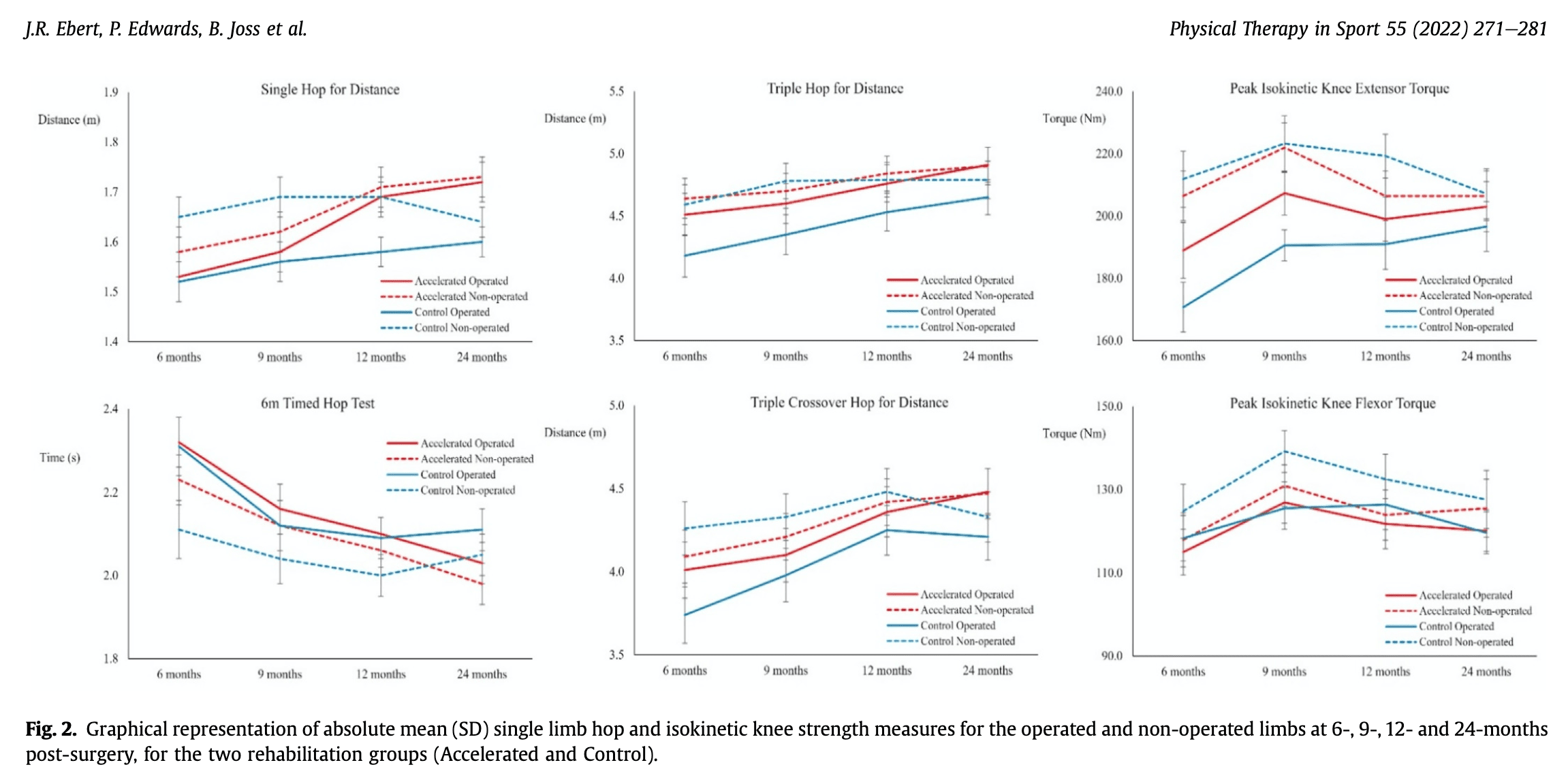

A relevant side-note with these graphs below:

The Single Hop for Distance graph shows an increase in hop distance for the operated and non-operated leg for the accelerated group, but a small increase in the operated leg for the control group. Furthermore, the non-operated limb shows a decrease in hop distance. The limb symmetry index is calculated by dividing the score of the affected leg by the score of the unaffected leg and by multiplying the outcome by 100. So this may have overestimated the real improvement in LSI as the denominator decreased.

This remark is also applicable to the triple hop for distance, peak knee extensor torque, and triple crossover hop for distance. When a decrease in the unaffected leg is seen, this will unfairly improve the LSI score. When you notice this, I would suggest not to interpret the increased LSI. Of course, over the study months, an increase in LSI for these hop tests is seen, but it would be incorrect to attribute an improved LSI at a specific time point to a real increase in hop performance in case the unaffected leg shows a decrease in hop performance. Here it would be more interesting to compare the outcome to the baseline outcome to correct for false improvements in LSI. It is important to have this in mind when interpreting LSIs from this study and future studies.

When the physical outcomes were combined in a “test battery”, even though the control group followed a structured and progressive rehabilitation program, there was still a very large proportion of patients not achieving the 90% threshold in at least one of the tests at every time point. At 24 months, this was, for example, two thirds in the control group compared to less than 20% in the advanced group not meeting the minimal 90% LSI in at least one of the physical tests.

Talk nerdy to me

Apart from the precautions mentioned above, this study had an excellent setup. Power calculations were done beforehand and the required number of patients was included. An intention-to-treat analysis was done and an independent assessor blinded to group allocation collected the outcomes. The study included a small sample but achieved important results from which can be built upon for future studies.

The surgical procedures were performed by one single surgeon and the study was held in 2 different hospitals. Because of this, we can assume that there was uniformity in the surgical procedures. Rehab was held in a private outpatient clinic and was supervised, although it was not specified by whom.

Important to notice is that the loading of exercises was not determined by 1RM testing, but it was “dictated on a case-by-case basis subjectively during an individual patient’s introduction to each new exercise and their exercise tolerance and competency in completing the repetitions required for the exercise set on each occasion.” This may have advantages and disadvantages, but especially in these recently operated patients, 1RM testing would be inappropriate in the context of the healing ACL. Progressions were based on a combination of factors including:

- time from surgery,

- concomitant surgery (in the earlier post-operative stages),

- proficiency of activities undertaken up until that point,

- quadriceps control,

- pain/effusion and knee ROM (e.g. the initiation of cycling was generally dictated by the patient’s active knee ROM being adequate for a full pedal revolution)

For allowing the return to sport (a delay beyond 9 months was advised), the restoration of full active knee extension and a flexion ROM LSI ⋝90%, ⋝90% LSI in peak isokinetic knee extensor and flexor strength, and ⋝90% LSI in hop tests was necessary. Although, this was more of an advice and it was not specified whether or not this was followed.

Take home messages

An accelerated ACLR rehabilitation protocol following ACL reconstruction does not harm the healing graft as no differences in laxity outcomes were observed between the group receiving an accelerated rehabilitation program compared to the control group. It significantly improved recovery of strength and functional capacity and more patients were able to return to pivoting sports at 12 months postoperatively.

Reference

FREE ACL Return-To-Sport Webinar

Watch this Free Webinar by Bart Dingenen – our ACL Rehab Expert. He will guide you through successful strategies to return your athlete to sport.