Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis | Diagnosis & Treatment

Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis | Diagnosis & Treatment

Articular cartilage, subchondral and periarticular bone, as well as periarticular soft tissues like ligaments, muscles, and synovium, are all affected by the degenerative joint disease osteoarthritis (OA). In addition to joint discomfort, stiffness, and movement restrictions, OA also causes radiological abnormalities such as osteophyte formation, periarticular cysts, and subchondral sclerosis. These characteristics of glenohumeral joint injury serve as the definition of GHOA (Ibounig et al., 2021).

Up to 17% of individuals with shoulder pain, a patient population that has tripled in size over the past 40 years, have degenerative abnormalities of the glenohumeral (GH) joint (Harkness et al., 2005).

It is important to note that the clinical and radiological definitions of OA differ. Radiological OA does not imply symptoms per se. Similarly, OA as a clinical diagnosis can go hand in hand with radiological changes that could be slight, as well as severe (Dieppe and Lohmander 2005). Many classifications exist in terms of radiological glenohumeral osteoarthritis (GHOA), that are not within the scope of this post.

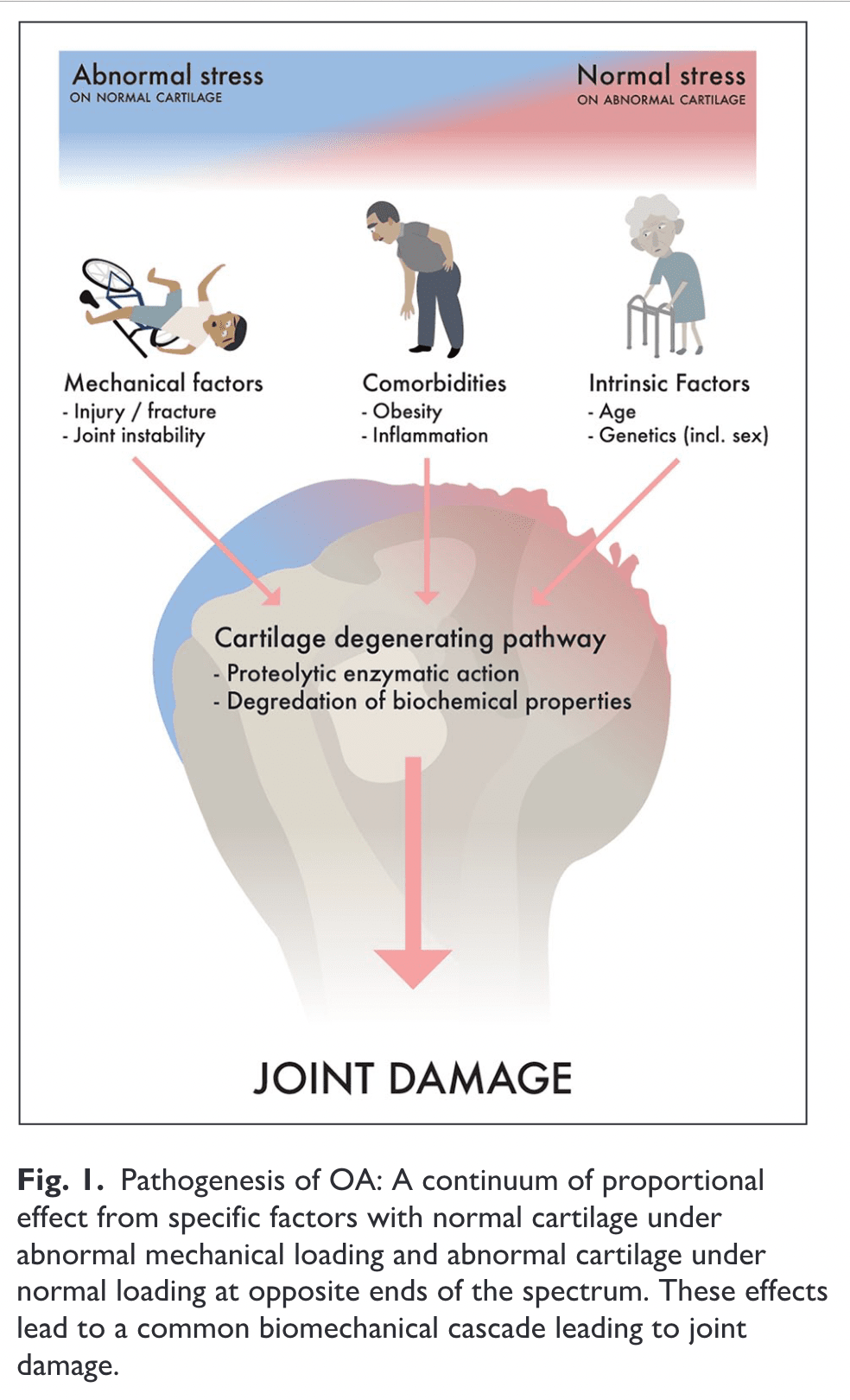

Pathophysiology

While both are abundant in bone, cartilage lacks both nerves and blood vessels. Good joint cartilage reduces friction and distributes static and dynamic joint loads. A collagen and proteoglycan-rich cartilage matrix is maintained by sparsely dispersed cartilage cells. For the cartilage to continue to function properly, the quality of this matrix is essential. Osteoarthritis causes changes in the joint cartilage that include progressive proteolytic breakdown of the matrix and enhanced chondrocyte production of the same, or slightly different, matrix components (Heinegård et al, 2004).

The most frequent bony change in GHOA is the formation of osteophytes, due to chondrocyte stimulation and enchondral ossification in the transition area of the hyaline cartilage and synovial membrane (Kerr et al., 1995).

The periarticular tissues like synovium and subchondral bone are densely innervated and are the most likely sources of nociceptive stimuli, whereas articular cartilage is generally insensitive (Kidd et al., 2004).

Symptoms like night and rest pain might potentially be caused by altered biomechanics or damaged cartilage, which would increase intra-osseous pressure in the subchondral bone but there is no sound proven theory. An individual’s perception of pain is influenced by local and central pain pathways, as well as contextual psychosocial and socioeconomic factors, in addition to local anatomical elements in and around the joint. As is occasionally observed in workers’ compensation cases, where compensation claims are frequently associated with worse outcomes, contextual factors like depression, anxiety, coping mechanisms, and the patient’s level of education may explain some of the frequently observed discrepancies between subjective symptoms and objective radiological findings of joint damage (Summers et al., 1988, Creamer et al., 1998, Koljonen et al., 2009).

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Clinical Presentation & Examination

Known Risk Factors

According to Ibounig et al (2021) and Michener et al (2023):

- Age

- Genetics

- Glenoid dysplasia

- Obesity (unclear)

- Excessive exercise

- Joint laxity

- Joint trauma: dislocation, fractures

- Rotator cuff arthropathy

- Overhead construction work

- Former weightlifters and throwing athletes

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Avascular necrosis

Clinical picture

A deep aching and activity-related joint pain, commonly posteriorly, in an older patient; usually 60 plus although it can occur before that. A passive ROM restriction is an important indicator of GHOA. Night and rest pain might also be present. Mechanical symptoms might arise after disease progression such as catching and locking.

Early-stage GHOA clinical examination results can be subtle, but as the disease advances, they become more obvious. Clinical signs include restricted passive range of motion, particularly external rotation, as well as joint line soreness on palpation, crepitus, and pain during joint movement. A rotator cuff arthropathy may be diagnosed if an examination reveals muscle atrophy or fluid accumulation (also known as the “fluid sign” or “geyser sign,” which occurs when synovial fluid from the glenohumeral joint leaks into the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa) (Ibounig et al., 2021).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by combining the clinical picture with a thorough patient history together with a physical exam and imaging studies (Michener et al., 2023).

The British Elbow and Shoulder Society (BESS) proposed the following criteria: pain for more than 3 months, no instability, no localized AC joint pain upon manual examination, a global reduction in ROM, particularly in passive external rotation with the arm at the side, and radiographs to confirm the diagnosis (Rees et al., 2021).

Imaging

An anteroposterior or axillary RX is the most common imaging technique to help diagnose GHOA. MRI might be useful for ruling out the differential diagnoses seen below (Michener et al., 2023).

Differential diagnoses

- Rotator cuff full thickness tear

- Rotator cuff related shoulder pain

- AC joint pain

- Frozen shoulder

- Shoulder instability

- Parsonage Turner syndrome

- Osteonecrosis

- RA

- Septic arthritis

- Crystal arthropathies

- Acromioclavicular OA

- Neoplasm

- Brachial plexitis

LEVEL UP YOUR ROTATOR CUFF DISORDER KNOWLEDGE – FOR FREE!

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Treatment

Medication

Strong evidence supports the frequent administration of oral paracetamol to reduce osteoarthritis-related pain in general (Bijlsma et al., 2002). It is risk-free and has a low incidence of side effects. Because they lessen pain brought on by inflammation and synovitis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have also been shown to be beneficial in the therapy of osteoarthritis in general. However, due to their large side effect profile, they are not advised as first-line treatments (Seed et al., 2009). Similar to this, opiate-based analgesia is not advised for long-term usage due to the adverse impact profile and dependence risk, even if it has been demonstrated to be effective for pain reduction (Jawad et al., 2005).

Corticosteroid injections

There is no evidence that supports the routine use of corticosteroid injections (Gross et al., 2013).

Suprascapular nerve block

The suprascapular nerve’s afferent fibers may get trapped by damaged tissues or get hypersensitive as a result of persistent, unresolved pain in patients with chronic shoulder discomfort. Several clinicians utilize suprascapular nerve block (SSNB) to treat both acute and persistent shoulder discomfort (Chang et al., 2016).

Surgery

Different surgical techniques exist to treat GHOA. The most common ones are listed below.

Arthroscopy

Loose body removal, osteophyte resection, debridement of chondral flaps or degenerative tissue, capsular release, biceps tenotomy or tenodesis, subacromial decompression, and joint lavage are among the procedures that may be involved here. One or more of these techniques may be used in younger patients where joint arthroplasty may not be suitable.

The multiple techniques involved make it hard to draw conclusions about the efficacy of the procedures.

Hemi-arthroplasty

Hemiarthroplasty is a surgical procedure in which the damaged humeral head is replaced with a prosthetic implant while preserving the patient’s natural glenoid socket. The technique is often used in proximal humeral fractures, however, the reversed total shoulder arthroplasty might result in superior outcomes compared to this one (Shukla et al., 2016, Ferrel et al., 2017).

Humeral head resurfacing

This replaces the damaged surface of the humeral head with a smooth prosthetic implant, preserving as much healthy bone as possible while restoring joint function in the shoulder. According to Soudy et al. (2017), the outcomes of this technique are favorable.

Anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty

This technique places a prosthetic on the glenoid and the humeral head, creating artificial joint surfaces. This surgical technique results in good outcomes in terms of function and pain (Flurin et al., 2013).

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty

Surgical procedure that involves replacing a damaged shoulder joint with a prosthetic implant in which the ball and socket components are switched, enabling the deltoid muscle to compensate for the loss of rotator cuff function and restore arm mobility. This technique is thus often used when the rotator cuff function is severely impeded. The procedure compares quite well to the functional and pain outcomes of anatomic total shoulder arthroplasties (Burden et al., 2021; Flurin et al., 2013).

Conservative care

Although many surgical options are described above, a Cochrane systematic review investigating several techniques (total shoulder arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty, arthroscopic debridement, interpositional arthroplasty, and cartilage repair/implant) concluded that it is unknown whether surgery for GHOA provides benefits over usual care or nonsurgical treatment (Singh et al., 2011).

The effectiveness of physical therapy as a stand-alone treatment has not been examined by any studies. In a trial by Guo et al., (2016) involving 129 patients aged 65 and older, sustained improvements in pain and function were observed after a 3-year follow-up as part of a multimodal treatment strategy.

References

Follow a course

- Learn from wherever, whenever, and at your own pace

- Interactive online courses from an award-winning team

- CEU/CPD accreditation in the Netherlands, Belgium, US & UK

Everything you need to know about stiff shoulders.