Achilles Tendinopathy

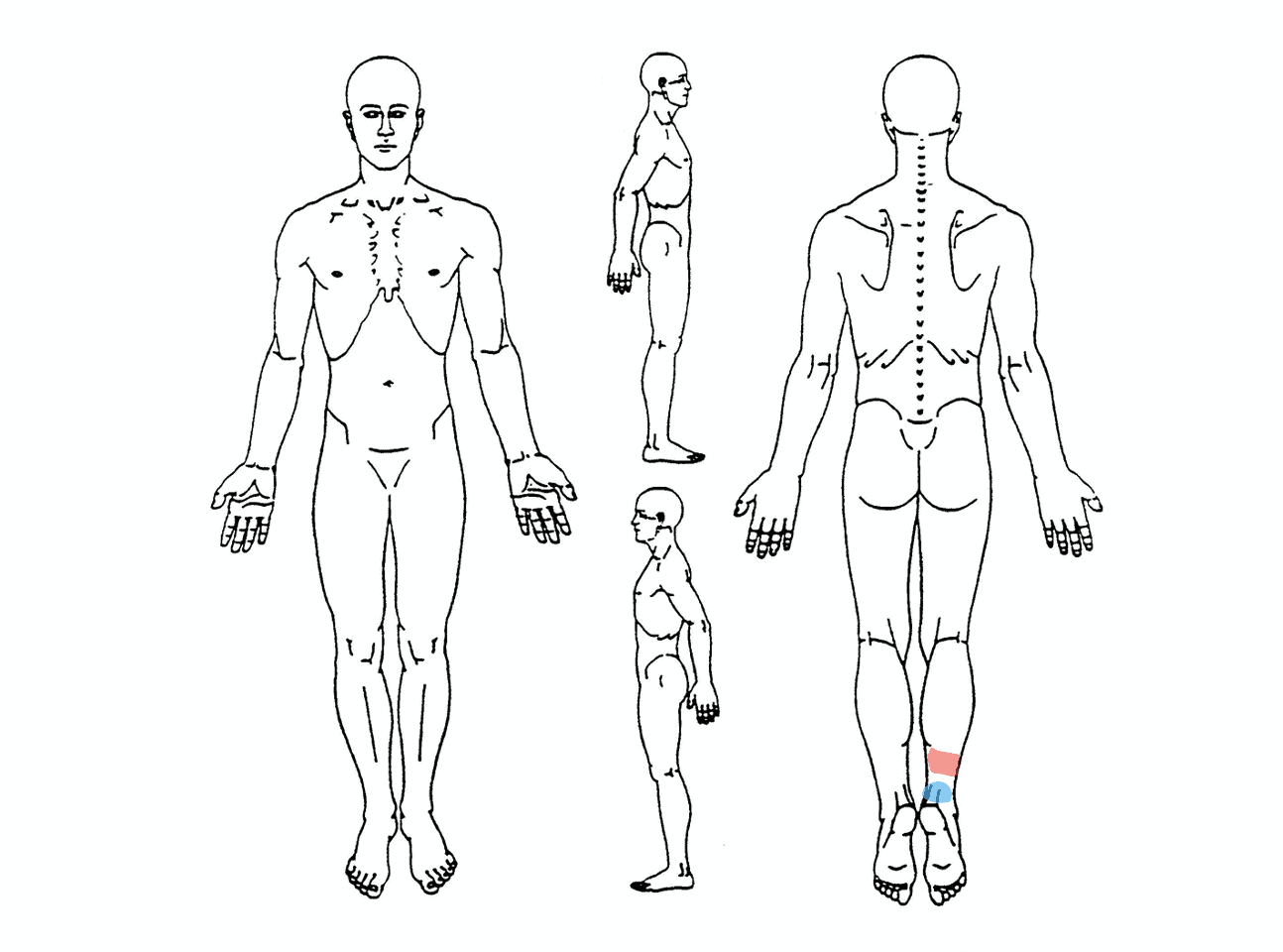

Body Chart

Often above insertion (tendon midportion 2-6cm)

Direct attachment/bony junction

Background Information

Patient Profile

- Prevalent in all groups

- Mostly running population

Pathophysiology

According to a study by Soslowsky et al. (2002) a combination of tensile load and extrinsic compression lead to the greatest injury in tendons. Intense loading of tendons results in net collagen degradation for up to 36h (Magnussen et al. 2010). This intense loading includes high and fast load activities. Not enough rest may lead to irreversible degenerative changes in the tendon.

A pathological tendon has more good structure than a normal tendon (Docking &Cook al. 2015). This means we can load these tendons because we have loads of good tissue. Any therapies for tendon pathology are not necessary, because we cannot change the structure of the pathological part anyways. For this reason, Docking and colleagues came up with the quote “Treat the donut, not the hole” – in other words, focus on the healthy structure and not the pathological part

Course

Intermittent pain, dependent on load; Pain can spontaneously reduce during activity and increase after; stiffness of the tendon after prolonged immobilization (e.g. sitting).

Positive results following a loading program can be expected after around 3 months although rehab can last >1 year in chronic cases.

History & Physical Examination

History

- Highly localized pain (patient can indicate pain region with 1-2 fingers)

- Hallmark Sign: Morning Stiffness

- Inspection: Muscle wasting of the calves

- Onset related to changes in training load (especially high and fast load activities)

- Pain maximal 24 hours after SSC activities

- Proportional pain/load relationship

Physical Examination

Inspection/Palpation

- Possibly visible thickening of the tendon or tendon interface;

- Muscle wasting of the affected calf

- Pain upon palpating the tendon (Midportion: 2-3cm above calcaneal insertion, at the insertion: Bone-tendon junction)

- PROM: Excessive as well as reduced dorsiflexion range of motion might be a contributing risk factor

Active Examination

- Proportional pain/load relationship: for example Calf raises < Single-leg calf raises with speed < hopping < hopping on one leg

- Calf strength/endurance with maximal single leg calf raise test

- Hopping: Assess pain and quality (the less ground contact the better) and faults (knee bending, heel slap)

Special Testing

Differential Diagnosis

- Achilles tendon rupture: Thomson Test

- Paratenonitis: Crepitus, excessive swelling, pain during any movement (even unloaded), nodule does not move upon the Arc Test

- Sural nerve neuropathy: Diffuse lateral Achilles or heel pain, burning quality, paresthesias, radiating into lateral side of the foot, positive Straight Leg Raise Test with ankle in dorsiflexion and inversion

- Posterior Impingement: Pain provocation with maximal passive plantar flexion

- Plantaris tendinopathy: Medial pain, MRI confirmation necessary

- Accessory/low soleus: Compartment-symptom like syndromes (e.g. pain with running that settles directly when stopping), MRI confirmation necessary

Treatment

1) Pain reduction

- Reduce/avoid SSC activities that lead to pain > 24 hours after activity

- Avoid stretching or rubbing the irritated tendon

- Avoid flat shoes or not wearing shoes for insertional Achilles tendinopathy

- Consider Ibuprofen for a limited period of time

- Try isometric Calf Raises 4x 45 seconds with 2 minutes rest in between sets and at least 70% of the maximal voluntary contraction

- Consider heel wedges for insertional Achilles tendinopathy

2) Slow and heavy resistance training

- No evidence of superiority of isometric, concentric or eccentric training

- Frequency: 2-3 times per week

- Rep range: 6-15 repetitions

- Pain: Tolerable pain allowed if it settles after 24 hours

- Cadence: 3-0-3 (use metronome if necessary)

3) SSC training / Energy-storage and release exercises

- Entry-level: Pain <3/10 NRS, 20DL hops don’t irritate (Sancho et al. 2020)

References

- Barry, N.N. and J.L. McGuire, Overuse syndromes in adult athletes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am, 1996. 22(3): p. 515-30.

- Carcia, C.R., et al., Achilles pain, stiffness, and muscle power deficits: Achilles tendinitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2010. 40(9): p. A1-26.

- Rosso, C., Evidenzbasierte Therapie der Achillessehnen-Tendinopathie und -Ruptur, P. Vavken, Editor. 2012, SportOrthoTrauma. p. 250-257.

- Böhni, U., Seiten aus dem Handbuch Manuelle Medizin. S.12-15, Theorie des Reizsummenprinzip am WDR-Neuron (Ikeda 2003, Sandkühler 2003). 28.10.2011, Thieme Verlag.

- Alfredson, H. and R. Lorentzon, Chronic Achilles tendinosis: recommendations for treatment and prevention. Sports Med, 2000. 29(2): p. 135-46.

- Kvist, M., Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Med, 1994. 18(3): p. 173-201.

- Alfredson, H., et al., Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med, 1998. 26(3): p. 360-6.

- van der Plas, A., et al., A 5-year follow-up study of Alfredson’s heel-drop exercise programme in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med, 2012. 46(3): p. 214-8.