Beliefs on Biopsychosocial Factors Contributing to Chronic Pain of Musculoskeletal Origin

Introduksjon

Despite decades of research and increasing adoption of a biopsychosocial framework, outcomes for people with chronic musculoskeletal pain remain poor, and prevalence continues to rise. Clinicians often sigh because of the difficulties when working with people with chronic pain. One of the difficulties is that the focus must be placed on biopsychosocial factors, instead of on local tissue factors.

While physiotherapists are well aware that psychological and social factors influence pain, most existing research has focused on patients’ biomedical beliefs (e.g., “damage”, “degeneration”), or explored psychosocial factors as consequences of pain rather than contributors. Critically, no previous qualitative studies have explicitly asked people with chronic musculoskeletal pain whether they believe psychological or social factors contributed to the development or persistence of their pain. This represents a major gap, because patient beliefs strongly influence engagement with exercise, openness to psychologically informed care, fear avoidance, and catastrophisation, and ultimately long-term disability. This study, therefore, explored patients’ explanatory models of chronic musculoskeletal pain to specifically examine beliefs about psychological and social contributors, not just biological ones. This study aimed to understand what factors people believed contributed to their chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Metoder

The study is rooted in a qualitative preliminary design, which serves as the crucial first step in a broader research initiative. The current study is an exploratory analysis of patient interviews.

A sample of six participants with chronic musculoskeletal pain, present for at least 3 months, were invited to participate. These participants were recruited from the general public through advertising on patient and public mailing lists at the University of Birmingham, specialist interest groups, and social media.

Data was collected through one-to-one semi-structured interviews. The study’s interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom with participants at their homes. Each interview lasted between 50 and 70 minutes and took place within three weeks of informed consent. The interview schedule, informed by the biopsychosocial model and patient input, was designed to elicit participants’ honest, uninfluenced beliefs about all contributing factors to their chronic musculoskeletal pain. The researcher had no prior relationship with the participants.

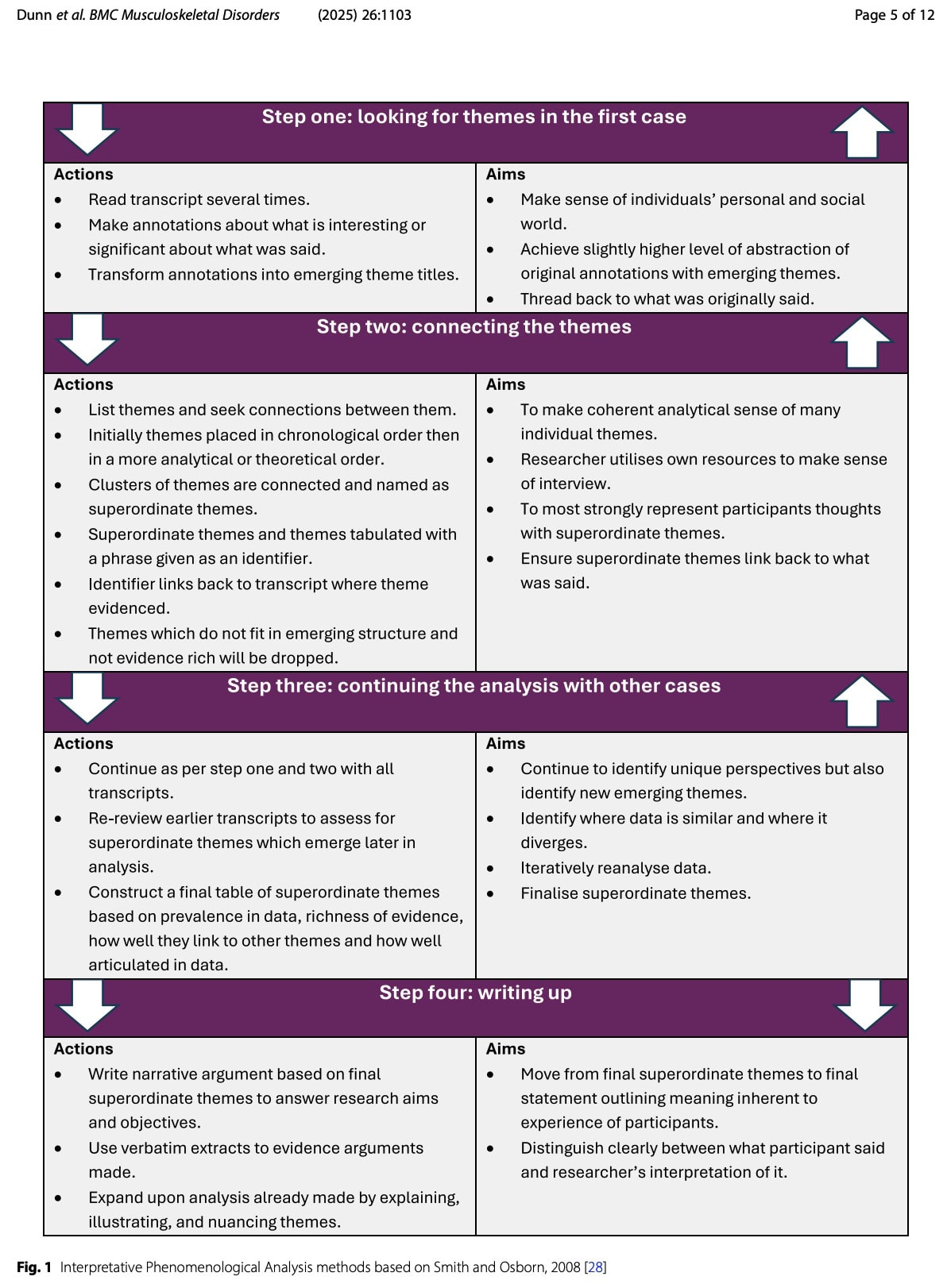

The data from the interviews were interpreted using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which is a systematic qualitative approach suited for gaining in-depth understandings of personal experiences. In this case, it focuses on how individuals make sense of their persistent pain by analysing the lived experiences of a small group of participants, focusing on their subjective perceptions and interpretations.

The IPA contains four iterative stages:

- Detailed reading and initial coding of each transcript

- Development of superordinate themes

- Cross-case comparison

- Narrative synthesis supported by verbatim quotes

Resultater

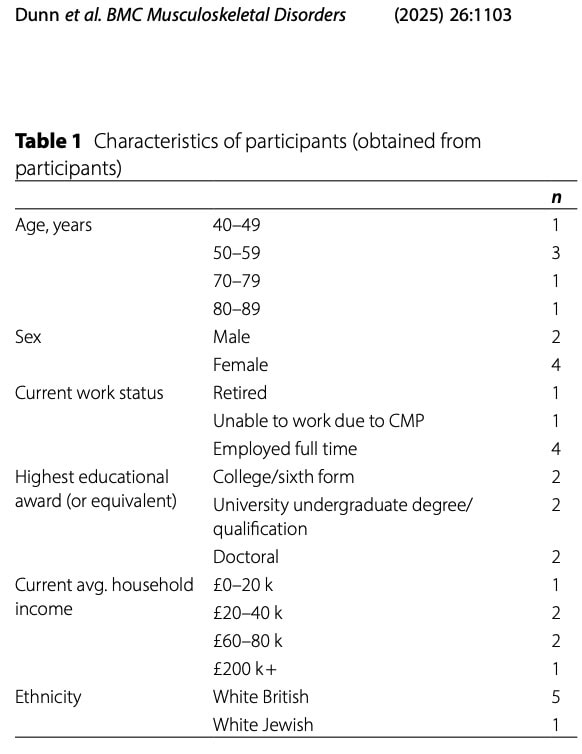

Six participants were included: two males and four females. Four of the participants were working full-time, 1 was retired, and 1 was unable to work due to experiencing chronic musculoskeletal pain.

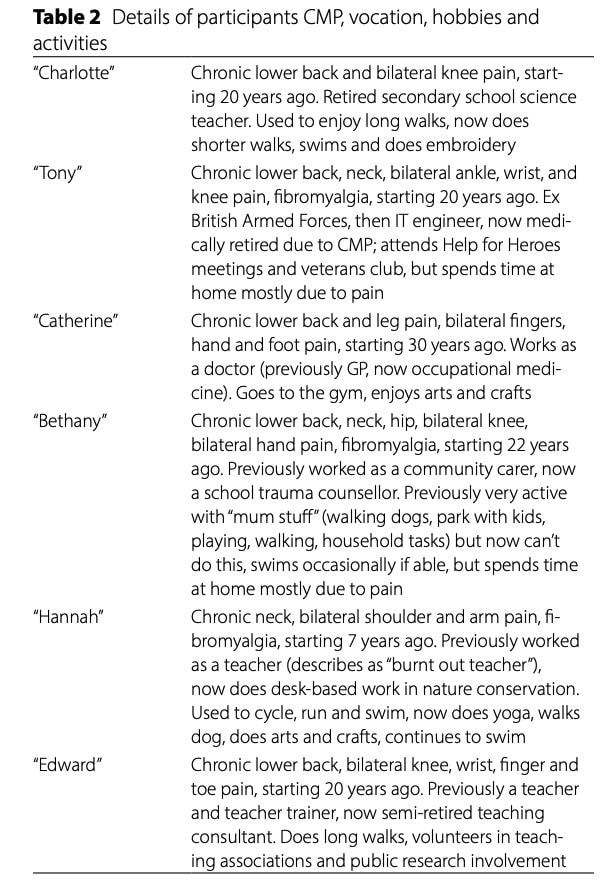

Their pain presentations were diverse; all participants experienced pain at multiple locations, as shown in the table below.

Disability levels varied, and the authors classified the participants into 3 groups based on the impact their chronic musculoskeletal pain had on their lives:

- Two participants experienced a high impact of their chronic musculoskeletal pain on their lives. They reported having significantly reduced or modified their activities, including stopping work: Tony, Bethany

- A moderate impact was reported by two participants, who had changed some activities (activity modification): Catherine, Hannah

- The last two participants indicated a low impact of their chronic musculoskeletal pain and had their activities largely maintained: Charlotte, Edward

The results from the interviews indicated that six superordinate themes emerged, structured around psychological, social, and biological beliefs.

Superordinate theme 1: Negative psychological experiences do not contribute to chronic musculoskeletal pain

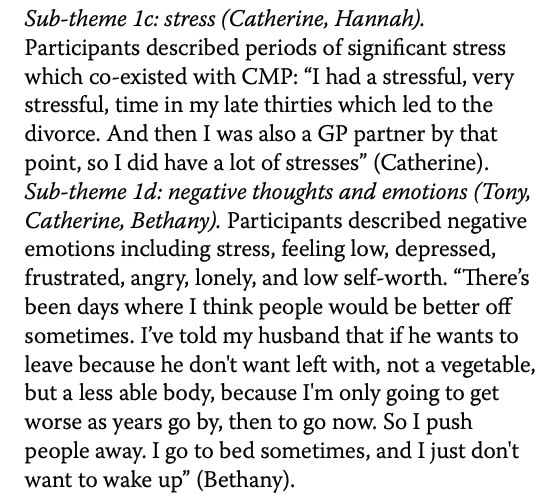

The affected individuals who had a high or moderate impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain on their lives described negative psychological factors, including psychological distress, loss of self-identity, stress, and negative thoughts and emotions, in relation to their chronic pain.

When asked about their beliefs about whether these factors contributed to their chronic pain, all denied that these psychological experiences contributed to the development of or persistence of their pain. For them, it was merely distress as a reaction to pain, rather than a driver of it.

Superordinate theme 2: Unsatisfactory healthcare contributes to chronic musculoskeletal pain

Two of the six participants described a negative experience with healthcare as being contributory. Both had a high impact of their chronic pain on their lives.

Superordinate theme 3: Maladaptive coping strategies do not contribute to chronic musculoskeletal pain

All participants with high and moderate impact spoke about their thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours toward managing chronic musculoskeletal pain, which were in keeping with known ‘maladaptive coping strategies’. This included catastrophisation, avoidance, and an external locus of control.

When they were asked if these maladaptive coping strategies affected their chronic pain, all agreed that it did not contribute to their pain. When asked if stopping or avoiding activities may have made their chronic pain worse stated: “The things that we’ve mentioned? No, no, it helped. They all helped”. Tony (high impact profile) acknowledged that avoidance may have made his chronic pain worse. In contrast, both participants who had a low impact of their pain on their lives did not describe maladaptive coping strategies.

Superordinate theme 4: Positive coping strategies improve chronic musculoskeletal pain

Participants with low and moderate impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain on their lives described thoughts, beliefs, and behaviours in keeping with positive coping strategies, and believed these improved their pain by reducing it or preventing it from worsening.

Participants with positive coping strategies believed that their chronic pain was better because of their approaches. Edward articulated this well for exercise and a positive attitude: “as these [joints] are living things, they presumably have the power to keep themselves repaired as much as possible. So, I believe that usage does continue to help the repair process, and non-usage tends to encourage it not to repair, and therefore to get worse”. “I think a positive attitude is the most important thing; not saying ‘oh, dear, I shall never walk again’ which presumably some people do say”.

Superordinate theme 5: Historical activities contribute to chronic musculoskeletal pain

Participants described past experiences including work, exercise, and hobbies, which they believed contributed to their CMP based on the perceived impact of the activity on structural changes.

Superordinate theme 6: Biological factors are the main reason for chronic musculoskeletal pain

All participants articulated biological factors they believed contributed to their chronic musculoskeletal pain, including structural changes and posture. Participants often based other beliefs, such as psychological or social factors, on their ability to link these back to perceived biological factors; for example, Tony stated, “I’ve definitely got arthritis in both my wrists, and that could be related from, I’d say, the IT work and the way, the position the hands are all the time”. This suggests that biological factors were the overarching belief to explain chronic musculoskeletal pain. Furthermore, at the end of the interview, participants were asked to identify their “main” belief about the cause of their chronic musculoskeletal pain, with five participants citing biological factors.

Spørsmål og tanker

How should we look at the current results? First of all, we have to understand that the identified themes are coming from only 6 people, at a specific location, bound to a certain healthcare system. We can in no case generalize these findings to all patients suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain. But that was not the aim of the researchers. By using the IPA methods of analysis, the depth of a topic is prioritized over breadth. The objective was not to quantify the prevalence of pain experiences across a large population, but rather to achieve a profound and detailed understanding of how individuals make sense of their pain. This focus on rich, experiential data is fundamental to IPA, and is intended to give insights into the meaning-making processes, cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions of living with pain that might be missed by purely quantitative methods. We can use the examples coming forward from these individuals to get to understand their way of thinking about chronic pain better. With this information, we could identify belief patterns that may act as barriers to effective physiotherapy interventions.

The dominant, overarching theme was the belief that biological factors are the cause of chronic musculoskeletal pain. All participants highlighted that structural changes in their bodies were causing their pain. Even participants who acknowledged stress or emotions ultimately returned to biological explanations, suggesting that psychosocial factors were only acceptable insofar as they could be translated into structural or mechanical mechanisms. When asked directly about the main cause of their pain, five of six participants identified biological factors. This framing appeared to organise all other beliefs, with psychological and social experiences interpreted as secondary, consequential, or irrelevant.

Participants pointed out that the structural changes in their bodies leading to chronic pain were caused by a sort of wear and tear. Work was believed to have caused cumulative wear, poor posture, or injury. Sports and physical hobbies were seen as having “put the body through too much”, leading to degeneration years later.

Coping strategies seemed to contrast between participants with high and moderate disability versus those with low or moderate disability. The first group generally described maladaptive coping, including catastrophisation, avoidance, and an external locus of control. The latter had more adaptive or positive coping strategies, think of solution-focused behavior, positive attitudes, movement and exercise.

- Those with high impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain showed more

- Catastrophic thoughts, often centred on exaggerated beliefs about structural damage (e.g. “crumbling discs”, “bone on bone”).

- Avoidance behaviours included stopping exercise, reducing activity, increasing rest, changing jobs, or leaving work entirely.

- External locus of control was evident in reliance on medications or medical solutions as the only means of relief.

- Those with moderate to low impact of pain on their lives talked about more

- Solution-focused coping: participants described seeking information, reframing their condition, problem-solving, and taking ownership of management decisions. Pain was viewed as something to work with rather than fight against.

- Positive attitudes: this included self-reassurance, rationalizing flare-ups, perseverance with valued activities, and maintaining a sense of control. These participants often contrasted themselves implicitly with others who might “give up” or catastrophise.

- Exercise as a positive coping strategy: participants believed that continued use of their bodies was beneficial, often framing this in quasi-biological terms (e.g. joints needing use to stay healthy). Even when pain was acknowledged, activity was not seen as threatening.

Crucially, most participants did not believe these maladaptive coping strategies worsened their pain. On the contrary, avoidance and rest were often perceived as helpful or protective against further damage. Even when explicitly asked whether such behaviours might be factors contributing to chronic pain, participants generally rejected this notion.

This altogether implies we need a different approach in practice. Rather than framing someone’s pain around the presence or absence of structural “damage”, which is often the case in a variety of medical care settings, we should explore the beliefs of the person in front of us. When distressors and known maladaptive factors contributing to chronic pain are identified, we could start by validating this experience without assigning causality. By implementing pain neuroscience education and explaining how it can increase nervous system sensitivity, rather than pointing to someone’s psychology, we can try to give a sense of understanding to that person. For example, someone with unexplained pain who has heard that he will have to live with it and who was told that “nothing” can be done about it, since “everything” has been tried (which is something I personally frequently encounter in practice), you could validate their experience by saying for example: “Given everything you’ve been dealing with, it makes sense that your nervous system is on high alert, but that doesn’t mean it is ‘in your head”.

For those who had negative experiences with previous healthcare encounters, we must be aware that there might be still an open door for us to regain their trust in healthcare providers, but be aware that there might be feelings of mistrust and anger toward “the system”. Here, your first focus should be on improving the therapeutic alliance. Be aware that most of these patients have been told to do A or B. They “have tried everything”, yet “everything failed”. In these circumstances, in clinical practice, I tend to shift the focus to try to find what has not been “done” yet. Sometimes, you can ask about what has been unhelpful versus what has been helpful so far. Or what they think they need to make this encounter feel different from past experiences. Take time to try to differentiate your approach from prior unhelpful encounters. And try to let them express what is in their thoughts, rather than filling the silences. Your interventions will need to be consistent, transparent, and filled with empathy, and create a safe space. But try to implement collaborative reasoning to make the patient feel part of the process, rather than “an object receiving a certain treatment”. Avoid being overly optimistic or using generic reassurance, like for example “I will fix it for you”, “everything will be fine”, but try to use collaborative language like “let’s figure this out together”. And most importantly, explain why you are doing something, rather than explaining what you are doing. Graded exposure can be used as a strategy to explore what the body is capable of, and you can frame it as a way to test the nervous system responses.

Theme 3 highlights that patients with high and moderate disability commonly adopt coping behaviours such as catastrophisation, activity avoidance, and an external locus of control, yet do not perceive these strategies as contributing to their chronic musculoskeletal pain. In physiotherapy practice, this means that avoidance and rest may be actively defended as protective rather than recognised as potentially contributing to pain. By labelling these behaviours as maladaptive or attempting to correct beliefs, resistance may be felt which probably undermines your therapeutic alliance. Therefore, prioritize your assessment around understanding the patient’s reasoning behind avoidance and their expectations of harm rather than immediately challenging these views. Interventions may be more effective when graded activity and exposure are framed as safe experiments to gather evidence about (tissue) tolerance, rather than as treatments aimed at changing beliefs. This approach allows physiotherapists to promote functional change while respecting patients’ existing explanatory models of their pain.

Snakk nerdete til meg

The reporting of this qualitative study adheres strictly to the COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) guidelines. This commitment ensures maximum transparency and methodological rigour, allowing readers to fully appraise the credibility and transferability of the findings. Adherence to COREQ demonstrates a commitment to high-quality qualitative reporting practices.

A limitation of the study is the small sample size (6 participants). Also, three different groups of disability levels were established by classifying these people based on the impact their chronic musculoskeletal pain on their lives. Although this can lead to a broader understanding of factors contributing to chronic pain, the classification of these categories was not based on a standardized method.

Ta med hjem meldinger

Those who experience the greatest disability from chronic musculoskeletal pain may be the least likely to endorse biopsychosocial explanations for their condition, despite often presenting with severe distress and maladaptive coping.

When working with people who have chronic musculoskeletal pain, before we start their rehabilitation program, it is important to explore their unique situation. As part of their story and their pain picture, we can explore their beliefs about the nature of the injury or pain they are experiencing.

Belief assessment and therapeutic alliance will likely be prerequisites for effective intervention, particularly in individuals with entrenched biomedical explanatory models. Attempts to directly modify beliefs or introduce psychosocial frameworks without adequate trust may risk disengagement or reinforce resistance. In the clinic, it might be better to start with behaviour change strategies like graded activity or exposure before trying to change beliefs. This lets patients feel safe and capable before they think differently about what caused their problem. So, it’s really important to use flexible, patient-focused communication that puts function, trust, and learning through experience first, rather than immediately trying to change their mind.

Referanse

Hvordan ernæring kan være en avgjørende faktor for sentral sensibilisering - Videoforelesning

Watch this FREE video lecture on Nutrition & Central Sensitisation by Europe’s #1 chronic pain researcher, Jo Nijs. Which food patients should avoid will probably surprise you!